Arts Reconsideration: The 1971 Project — Celebrating a Great Year in Music (July Entry)

Arts Reconsideration: The 1971 Project — Celebrating a Great Year in Music (July Entry)

Pushing back, resisting, full-out rebelling: 1971 was not far away from the watershed year of 1969, and the long-haired rebels (and close-cropped comrades) of the era were not finished quite yet. From writing songs alone in the woods and resisting the fame game (Jonathan Edwards), to telling stories of the outcast and bleary-eyed truckers by mixing up musical genres (Little Feat), to bitter shouts of rage against the inhumanity of the prison system (Eric Burdon and Jimmy Witherspoon), to breaking off from a popular group to form a new band with electric violin and naming their album after toilet seat covers (Hot Tuna), to outright propaganda for full-scale Cultural Revolution (The Red Detachment of Women), the entries for this month demonstrate the commitment and passion that would be harder to find later in the decade. These diverse albums may not be familiar to you now, but they made indelible marks in their own time and continue to resonate 50 years later. We hope you’ll check them out and let us know your reactions in the comments below.

For those who missed them, here are the 1971 music entries for February, March, April, May, and June.

— Allen Michie

Little Feat, Little Feat (Warner Bros.)

Textured, varied, steeped in blues and roots, Little Feat’s startling debut had just about everything you needed — cutting slide guitar, teary-eyed country-folk ballads, warped second-line stomps, a Howlin’ Wolf medley, and stories. Oh, the stories! It’s a myth-scape of long-haul truckers traversing the Southwest, world-weary and brokenhearted, peddling dope, getting in and out of scrapes, ticking off place names one after the other: “Tucson to Tucumcari/Tehachapi to Tonapah,” as Lowell George sings in one of several deathless lines in his ballad-standard classic “Willing” (covered by Linda Ronstadt on Heart Like a Wheel). Every song seems driven by its own internal logic and form, defined by the acid-etched lines of Lowell’s electric slide and pliant voice, by turns growling, moaning, or even yearning tragically over a country-pedal steel (“I’ve Been the One”) or finding Biblical-romantic apotheosis amid church organ and strings (“Brides of Jesus”). It’s a rich bounty of song — think of Little Feat 1.0 in its own way as a version of the Band, nearly as virtuosic, its touchstones the highway-riding Americana mythology of the Southwest, with a touch of the substance-fueled surreal rather than the hoedowns and heartbreaks of ol’ Dixie.

Textured, varied, steeped in blues and roots, Little Feat’s startling debut had just about everything you needed — cutting slide guitar, teary-eyed country-folk ballads, warped second-line stomps, a Howlin’ Wolf medley, and stories. Oh, the stories! It’s a myth-scape of long-haul truckers traversing the Southwest, world-weary and brokenhearted, peddling dope, getting in and out of scrapes, ticking off place names one after the other: “Tucson to Tucumcari/Tehachapi to Tonapah,” as Lowell George sings in one of several deathless lines in his ballad-standard classic “Willing” (covered by Linda Ronstadt on Heart Like a Wheel). Every song seems driven by its own internal logic and form, defined by the acid-etched lines of Lowell’s electric slide and pliant voice, by turns growling, moaning, or even yearning tragically over a country-pedal steel (“I’ve Been the One”) or finding Biblical-romantic apotheosis amid church organ and strings (“Brides of Jesus”). It’s a rich bounty of song — think of Little Feat 1.0 in its own way as a version of the Band, nearly as virtuosic, its touchstones the highway-riding Americana mythology of the Southwest, with a touch of the substance-fueled surreal rather than the hoedowns and heartbreaks of ol’ Dixie.

The band was the brainchild of George, formed with another refugee from Frank Zappa’s Mothers of Invention, bassist Roy Estrada, with keyboardist and fellow songwriter Bill Payne, and drummer Richard Hayward. They got some traction after critic Ed Ward praised the single “Strawberry Flats” as “a slab of out-and-out paranoia set to a nervous backing,” prompting (claimed Ward) a call from Warner Bros. and, eventually, this album. OK, maybe the Zappa connection had something to do with it too. But nervous paranoia, sure — along with a rock-and-roll sea shanty of sorts with a dollop of “Penny Lane” trumpet (“Crazy Captain Gunboat Willie”).

With subsequent semi-hits like “Dixie Chicken,” “Fat Man in the Bathtub,” and “Rock and Roll Doctor,” the band dove deeper into New Orleans funk and gained renown. But George, it’s said, grew disenchanted, and musical direction and personnel continued to shift, with a breakup and reformation over the course of a half-dozen albums. A reputed epic over-indulger in food, drugs, and alcohol, George died in 1979, while on tour for his solo debut, Thanks, I’ll Eat It Here. He was 34.

The band did have a later resurgence that has gone on for decades, but here we have their first flowering, and George’s trembling desire (and appetite), captured with total assurance, singing over guest Ry Cooder’s bottleneck slide guitar, the singer “warped by the rain/driven by the snow . . . drunk and dirty,” but somehow still on his feet, and willing.

— Jon Garelick

The Red Detachment of Women. Soldiers of the Women’s Detachment performing rifle drill in Act II, from the 1972 National Ballet of China production. Photo: Wiki Commons.

The Red Detachment of Women (China Record Corporation)

It is not much discussed today, but the Cold War was a boon for musical theater and cinema. Stalin, for example, was particularly fond of musicals. During his decades of rule over the USSR the Soviet filmscape changed from Dovzhenko’s experiments in 1930’s Earth (peasant struggles shown through “dialectical montage”) to Ivan Pyryev’s Bernstein-esque agrarian 1950 musical spectacular Cossacks of the Kuban. (The 1997 documentary East Side Story remains an excellent introduction to this genre.)

Emerging from the Great Famine, the People’s Republic of China followed the Soviet example and gave birth to the so-called “revolutionary opera.” In 1965, on the eve of the Cultural Revolution, The East Is Red premiered. A film adaptation arrived soon after. The show was based on peasant folk songs from the province of Shaanxi, which in recent decades had already been through several political transmutations, one of which was immortalized in the still-famous song “Nanniwan.” The East Is Red tells the story of the birth of the “New China” with the founding of the Chinese Communist Party. Its intense focus on Mao Zedong as “savior of the people” presaged what was to come. Although the Cultural Revolution officially ended in 1969, it continued, under its own momentum, to inspire musical entertainment.

The Red Detachment of Women however, tells a different, though parallel, story. The ballet was first performed in 1964 (it was based on a 1961 film). The movie focused on a maidservant in Hainan named Wu Qionghua who is freed from her cruel feudal lord by a Communist Party representative recruiting new soldiers for a Red Detachment of Women. Wu Qionghua learns to choose discipline and cooperation — over hatred and rage — when fighting against her former abusers. The ballet version was turned into a film in 1970, and in 1971 China Record Corporation (CRC) released the ballet as a three-record box set. The idea was to take advantage of the spread of consumer appliances. such as record players. In 1972, Nixon and Kissinger attended a performance of the ballet during their momentous China visit.

The year 1971 also saw the debut of the opera Raid on the White Tiger Regiment, which, along with The Red Detachment of Women, was elected as one of the Eight Model Operas of revolutionary form by Jiang Qing, Mao Zedong’s wife. At the time she was the leader of the so-called Gang of Four, which was charged with perpetuating Cultural Revolution policies. In 1976 Mao died, and the Gang of Four was disbanded shortly after. The CRC would later release disco-ize albums filled with old propaganda tunes, such as “Nanniwan.” Chances are this is how they would be recognized now, including songs from the distinctive The Red Detachment of Women, which served up a rare model of Maoist femininity.

When old women gather today to pollute the urban environment with the music streaming from their loud stereos as they perform their “plaza dances,” the chosen songs are often revamped revolutionary favorites. The cacophony ensures that The Red Detachment of Women and the transformation of Wu Qionghua shall not be forgotten.

— Jeremy Ray Jewell

Hot Tuna, First Pull Up, Then Pull Down (RCA Victor)

Hot Tuna’s second album, First Pull Up, Then Pull Down, clearly signals that guitarist Jorma Kaukonen and bassist Jack Casady were ready to take flight from Jefferson Airplane.

Hot Tuna’s second album, First Pull Up, Then Pull Down, clearly signals that guitarist Jorma Kaukonen and bassist Jack Casady were ready to take flight from Jefferson Airplane.

Their departure from the influential and successful psychedelic pioneers was still a couple of years in the offing when First Pull Up came out in the summer of 1971. However, in hindsight, you can hear how the rambunctious and rustic sound that Kaukonen and Casady were cooking up in this side project was bound to collide with the progressive pop stylings the rest of the Airplane crew would eventually use to rebrand the ensemble Jefferson Starship.

Like Hot Tuna’s self-titled debut released a year earlier, First Pull Up is a live recording, this one taken from performances at Chateau Liberte, a rock and roll dive bar located in the mountains near Santa Cruz. Electric violin player Papa John Creach and drummer Sammy Piazza join Kaukonen, Casady, and harmonica player Will Scarlett (who also appeared on the debut album but would depart the lineup later in 1971). The acoustic blues that Kaukonen and Casady so deftly explored on their debut takes a back seat to an electrified excursion.

First Pull Up, Then Pull Down (a phrase you have probably seen in public restrooms that offer toilet seat covers) opens with the frenetic instrumental “John’s Other.” Creach’s electric violin summons a rollicking New Orleans blues that Kaukonen brilliantly plays off of with his finger-picking style (and Casady is practically channeling a sousaphone with his bass line).

That Crescent City atmosphere carries into “Candy Man,” a song by Rev. Gary Davis, whom Kaukonen never fails to celebrate on record and in performances to this day.

The first couple of Hot Tuna records are light on original songs, but we get a classic on First Pull Up with “Been So Long,” one of many Kaukonen tunes generated by his turbulent first marriage. The line “Been So Long” went on to also serve as the title to Kaukonen’s excellent 2018 autobiography.

Most of First Pull Up lives on in the Tuna-verse. “Keep Your Lamps Trimmed and Burning,” “Never Happen No More,” and “Come Back Baby” are still staples in the Hot Tuna repertoire, along with “Been So Long” and “Candy Man.” Even the rarely played Bo Carter song “Want You to Know” from First Pull Up resurfaced last year in a solo Kaukonen concert he performed for a livestream.

“John’s Other” was laid to rest with Creach when he died in 1994, but the violinist’s influence is very much alive in Hot Tuna’s ongoing explorations of psychedelic blues.

That ability to jump from one kind of record, lineup, or approach to another — without giving up anything hard earned or well learned from previous work — is a hallmark of Hot Tuna. It’s very likely why, after more than 50 years, Kaukonen and Casady continue to make inspiring music. Yes, it’s a lot of old songs, but none are the same old song. And that’s a course that is set on First Pull Up, Then Pull Down.

– Scott McLennan

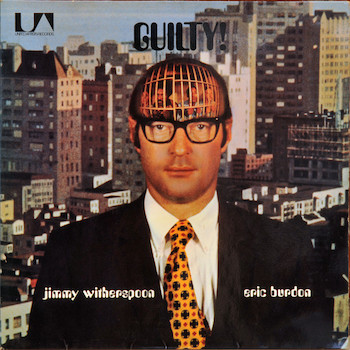

Eric Burdon and Jimmy Witherspoon, Guilty! (MGM)

You’ve probably never heard of this record, but if I had to take just one blues album to a desert island (where I would most certainly have the blues), this would be it. This isn’t blues that more-or-less sounds like the blues, for people who don’t really have them. This is the real thing.

You’ve probably never heard of this record, but if I had to take just one blues album to a desert island (where I would most certainly have the blues), this would be it. This isn’t blues that more-or-less sounds like the blues, for people who don’t really have them. This is the real thing.

I bought this LP from the 99-cent sale rack when I was just a teenager. I knew nothing about the musicians, and I confess I picked it up for the kitschy album cover. This image was a doozy — a nerdy corporate guy in an urban high-rise office has an image of four prisoners behind bars superimposed on his forehead. When I got home and put on the music, it was my own mind that got taken over. We all probably remember our baptism into the blues, and this was mine.

Burdon, lead singer for the Animals, isn’t an obvious choice to headline a blues album. The Animals broke up in 1969, and Burdon left rock for funk, joining the pioneering group War. They produced a few hit singles, including “Spill the Wine.” A two-disk set, The Black-Man’s Burdon, was released in 1970. Burdon left War (or, better, War left Burdon) after he collapsed on stage from an asthma attack. When Jimi Hendrix died in London in September 1970, it was after jamming with Burdon and War. It took years for Burdon to recover from the trauma.

Burdon shares vocal duties 50/50 with the great Jimmy Witherspoon, an established blues master since the early ’50s. He brings every ounce of his hefty presence and authority to the session without a trace of condescension to his more famous white rock star co-headliner.

Guilty! is a concept album: it’s about getting released from prison, dealing with the survivor’s guilt of being out, and the very real fear of getting hauled in front of an unmerciful judge for something as minor as a traffic violation. Burdon and Witherspoon share the vulnerabilities of victimhood: cops are prejudiced against both the hippies and the blacks. Every track is intense, honest, and gripping. The sometimes-graphic lyrics pull no punches.

The horns are out of tune. The mix is iffy. But damn, when the guitars come in already smoking on “Have Mercy Judge,” you can hear the sweat and anguish. The music doesn’t rock so much as it lurches with a kind of slow-drag funk. Burdon and John Sterling (extraordinary guitarist on the session) wrote “Soledad,” a searing portrait of the ironic suffering that comes with freedom: “As I drove my air-conditioned car/I can feel the pain coming through the door./What could it be, what this country’s doing to me?/When I can ride this ride, and just on the other side/Of the wire, running higher, are my brothers ‘neath the sky.” The guitars preach.

It was brilliant to include the standard “Going Down Slow” (“Somebody please write my mother, tell her the shape I’m in”), and to record it not with a bunch of studio pros, but live on the inside with the San Quentin Prison Band. You can hear the wind in the microphone, the pain in Witherspoon’s and Burdon’s voices, and the will to freedom in the guitar solo.

There were ongoing legal struggles involving the two different record labels that had signed War and Burdon, so Guilty! received no promotion (hence the 99-cent bin). The IRS claimed Burdon owed back taxes, so the group wasn’t allowed to tour or leave the US. Burdon brings all of this to the session — his raw rock voice, his funk sensibility from War, his sense of being screwed over by The Man, and his restless sense of being hounded by unrelenting officers with badges. Witherspoon balances it all with the world-weary baritone shouts of an older black man who’s been there and expects to be there again.

The album was rereleased in 1976 and reissued on CD in 1995 (MCA) and 2003 (BMG) as Black & White Blues, losing the grungy original cover. It was replaced with a smiling and dapper Witherspoon and Burdon, comfortable on a nice clean bus. The reissue completely downplays the prison theme, but once the shiny little digital disk is in the drive, there’s no cleaning up the grit, dust, heat, and throbbing pain of the blues.

-Allen Michie

Jonathan Edwards, Jonathan Edwards (Capricorn)

When music fans debate the greatest debut albums of all time, they commonly bring up certain discs: Led Zeppelin I, the first Boston album, the first Cars album, the first Doors album, Crosby, Stills & Nash, King Crimson’s In the Court of the Crimson King. But no one ever mention’s Jonathan Edwards’s eponymous debut platter. Released in November 1971, its 12 songs are short but very well written, and they linger in your mind long after the needle lifts. This writer feels it’s right up there with the best singer-songwriter albums of the era.

When music fans debate the greatest debut albums of all time, they commonly bring up certain discs: Led Zeppelin I, the first Boston album, the first Cars album, the first Doors album, Crosby, Stills & Nash, King Crimson’s In the Court of the Crimson King. But no one ever mention’s Jonathan Edwards’s eponymous debut platter. Released in November 1971, its 12 songs are short but very well written, and they linger in your mind long after the needle lifts. This writer feels it’s right up there with the best singer-songwriter albums of the era.

Edwards was a local boy at the time, having moved to Boston from Minnesota in 1967 with his band Sugar Creek. He decided to go solo in 1970 and recorded his first album at Intermedia Sound in Boston. Of course, where else but Boston would there be confusion between a 20th-century singer-songwriter and his 18th-century namesake, the New England theologian Jonathan Edwards (best known for his sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” and for being the grandfather of Aaron Burr)?

All the songs are written or co-written by Edwards except for “Don’t Cry Blue” and the haunting ballad “Sometimes,” written by former Sugar Creek bandmate Malcolm McKinney. While backed by five musicians, it’s a very light backing, so Edwards’s vocals and acoustic guitar are at the fore throughout the album. This gives it the intimate feel he was looking for when he decided to go out on his own.

In a much-repeated quote from an early bio, Edwards said, “I just went out in the woods every day with my bottle of wine and guitar, sat by a lake near Boston and wrote down all those tunes, day after day.”

Jonathan Edwards is anchored by the platinum single “Sunshine,” a dour song given a poppy delivery, that apparently alluded to Nixon and Vietnam (“He can’t even run his own life/I’ll be damned if he’ll run mine”). “Athens County” bring the country factor up considerably, as does “Shanty,” the good-timey ode to toking that features the immortal line, “We gonna lay around the shanty, mama, and put a good buzz on.”

The piano player Jef Labes, another Boston-based musician who just the year before had played on Van Morrison’s Moondance album, has nice features on a couple of songs: “The King,” a political thriller in the vein of Tim Buckley’s more progressive work, and “Jesse,” a reflection on childhood focused on a little girl at play.

Though not written by Edwards, “Sometimes” is this writer’s favorite song from the album, a touching lament about lost love. The very next song, the LP’s closer, is the rousing “Train of Glory,” which suggests that redemption is right around the corner. For Edwards, though, the success of his first album meant a loss of quietude and privacy, so he moved to a farm in western Massachusetts and has kept a decidedly lower profile ever since.

— Jason M. Rubin

Tagged: Allen Michie, Capricorn, China Record Corporation, Eric Burdon and Jimmy Witherspoon, First Pull Up Then Pull Down, Gullty!, Hot Tuna, Jeremy Ray Jewell, Jon Garelick, Jonathan Edwards, Little Feat, Scott McLennan