Arts Reconsideration: The 1971 Project — Celebrating a Great Year In Music (February Entry)

Here’s yet one more fantastic thing about it no longer being 2020: it’s now the 50th anniversary of the excellent music that premiered in 1971. It’s a perfect invitation for a series of Arts Reconsideration articles revisiting classic and overlooked works from this remarkable year of music. Until the end of the year, Arts Fuse critics will offer a select number of 1971’s marvels each month.

Spend an hour or so listening to the conformist wash of today’s pop music on corporate-owned radio, then be astonished that there was once a time, five decades ago, when giants ruled the airwaves. Look at the variety of genres represented by a sampling of some of the #1 singles that year: there’s earnest singer-songwriter material (“Imagine” by John Lennon, “It’s Too Late” by Carole King), country (“I Never Promised You a Rose Garden” by Lynn Anderson), rock and roll (“Brown Sugar” by the Rolling Stones, “Get It On” by T Rex), soul (“Theme from Shaft” by Isaac Hayes, “What’s Going On” by Marvin Gaye), blues (“Ain’t No Sunshine” by Bill Withers, “Me and Bobby McGee” by Janis Joplin), and bubblegum pop (“Knock Three Times” by Tony Orlando and Dawn, “One Bad Apple” by the Osmonds). There’s even the odd unclassifiable hit record that wouldn’t get anywhere near the charts today (“Brand New Key” by Melanie, “Uncle Albert” by Paul McCartney).

The United States was having a tumultuous year in 1971. Richard Nixon was in his first term, and reelection shenanigans weren’t yet a gleam in his shifty eyes. American morale for the Vietnam War was falling fast, jumping off the cliff with the publication of the Pentagon Papers. The Supreme Court ruled that cities could use busing to desegregate public schools. The voting age was lowered from 21 to 18. The Cold War and the Space Race continued unabated.

By our current standards, however, it was a fairly calm and steadying year. The country was still sorting out what to keep and what to reject after the tumultuous ’60s. Moonwalks were out; stable orbits were in. Hippie clothes out were out; polyester pant suits were in. Dropping acid to Jimi Hendrix was out; smoking weed to James Taylor was in. The Yardbirds were out; the Partridge Family was in. Violent war protests were out; depressed resignation was in.

After 50 years, it’s time to begin sorting out the wheat from the chaff. Which albums from 1971 became classics in their genres? Which ended up having a lasting influence? Which retain their power to move listeners discovering them for the first time? Join in the conversation in the comments section. We want you to let us know your own memories and favorites. What have we missed? What is here that shouldn’t be? For those of you with transistor AM radios and allowance money jangling in your pockets in 1971, how did this music shape who you are?

— Allen Michie has graduate degrees in English Literature from Oxford University and Emory University. He works in higher education administration in Austin, Texas (home of Armadillo World Headquarters, which was just getting fired up in 1971).

- Weather Report: Weather Report (Columbia)

Weather Report’s debut album still holds up to close listening today, and in hindsight, it provides a weightier listen than some of the band’s last recordings. Throughout its existence, Weather Report (the band) was essentially a vehicle for loose compositions and collective improvisation by Joe Zawinul (here almost exclusively on electric piano) and Wayne Shorter (here on soprano saxophone) with rock and funk foundations that non-jazz people could respond to. Bassist Miroslav Vitous and his successor Jaco Pastorius were crucial partners and sometimes co-improvisers, and each defined the direction of his edition. The rhythm players always had more limited roles, but Zawinul saw them as color partners rather than merely timekeepers. (Here, in this first release, are the only appearances in the group of drummer Alphonse Mouzon and percussionist-vocalist Airto Moreira.)

Much has been made of the dividing line between the cerebral Vitous band and the arena-filling Pastorius band, but in this first LP, elements common to both editions are well-displayed—the preeminence of Zawinul’s ideas, with cores of melody and rhythm conditioned by his long run with Cannonball Adderley and a knack for writing tunes with wide popular appeal (example: “Mercy Mercy Mercy”); circular structures, usually in tunes by Shorter, using modal harmonies and open structures; Shorter’s super-spare approach to his horn, allowing others enough space to do more than simply accompany; electric modification and distortion as core sonic characteristics; a wide range of percussion instruments to decorate the space; vocal effects for additional color; exciting group forays into rave-ups and/or true out-music; studio manipulation of basic tracks, which was considered cheating until Weather Report showed they could do everything live if they wanted to; and (of course) the towering influence of Miles Davis.

Davis was the colossus of fusion – he had the stature and financial resources to make his studio sessions cauldrons of creativity, with the greatest stars of present and future jazz invited to contribute to the recipes. Each person who passed through those experiences in the late ’60s and early ’70s found himself (they were all men at the time) forever changed, and each took with him the elements he liked to make innovative music of his own. The first was Davis’ drummer Tony Williams, whose band Lifetime had two fire-breathing discs in the stores by mid-1970. Zawinul contributed the title tune and his keyboards to the sessions for Davis’ In a Silent Way (Columbia, 1969). “Orange Lady,” one of the Zawinul tunes on Weather Report, had its first recording in a Davis studio session that same year. Shorter wrote “Sanctuary” for Davis in 1969 as well, and that tune may be the clearest precursor to Weather Report. Vitous (who played just one week in ’67 with Davis) made his debut with a session recorded that year that included past and future Davis alumni John McLaughlin, Herbie Hancock, and Jack DeJohnette; their work foreshadows “Seventh Arrow,” a tune Vitous wrote for Weather Report. Weather Report was then a bold step for Zawinul, Shorter, and Vitous, and it stood as one of the freshest, most lyrical, and most innovative records to appear in the ’70s.

–Steve Elman

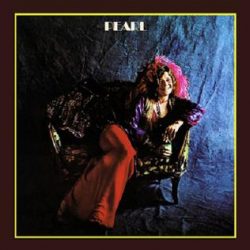

- Janis Joplin: Pearl (Columbia)

T he year 1971 was one of transition for me (and perhaps a few zillion other people). Moving back toward school after a couple of years of self-indulgence on the streets of Boston, I carried memories of some great music events attended, none better or more meaningful to me than Janis Joplin at Harvard Stadium on August 12, 1970. It turned out to be her final concert. The gloom of her passing less than two months later was only slightly lifted in January ’71 by the release of her final album, Pearl. The roadhouse roots of her last band gave the Texan a more natural setting. Instantly classic pieces like “Me and Bobby McGee” and “Mercedes Benz” joined with the wail of “Cry Baby” to reveal what might have been, but was for at least a while. The tough/tender “Get It While You Can” became one of her essential statements. Amen, Janis.

he year 1971 was one of transition for me (and perhaps a few zillion other people). Moving back toward school after a couple of years of self-indulgence on the streets of Boston, I carried memories of some great music events attended, none better or more meaningful to me than Janis Joplin at Harvard Stadium on August 12, 1970. It turned out to be her final concert. The gloom of her passing less than two months later was only slightly lifted in January ’71 by the release of her final album, Pearl. The roadhouse roots of her last band gave the Texan a more natural setting. Instantly classic pieces like “Me and Bobby McGee” and “Mercedes Benz” joined with the wail of “Cry Baby” to reveal what might have been, but was for at least a while. The tough/tender “Get It While You Can” became one of her essential statements. Amen, Janis.

–Steve Feeney

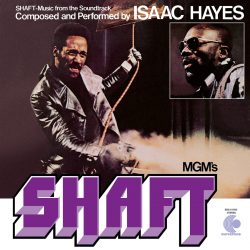

- Isaac Hayes: “Shaft”: Music from the Soundtrack (Enterprise)

The carelessly easy soulfulness of this album shouldn’t distract you from the genius of its compositions and arrangements. Hayes’ creativity and imagination shows its full range here—from the ominous funk of the hit title track to the breezy Wes Montgomery-style jazz groove of “Cafe Regio’s.” The horn section is used to powerful effect, and it is seldomly in quite the way you would expect: the horns play the punctuating role of the keyboardist’s left hand, a flute takes the high notes on top of the brass section, or a single trumpet plays in unison with the low end of a guitar. The title track opened up the evocative possibilities for R&B music, something the Temptations would pick up on a year later with “Papa Was a Rolling Stone.” Plus, eternal blessings to Hayes for making the wah-wah rhythm guitar and those 16th notes on the closed high-hat cymbal one of the iconic sounds of the ‘70s. The sound is forever attached to its era, but it has lost none of its funkiness or drive 50 years later. You can listen to Shaft as the soundtrack to a badass movie. Or you can free yourself of that limiting context and hear it as a kind of Black Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, bursting with ambition, melodicism, imagination, range, and musicianship.

The carelessly easy soulfulness of this album shouldn’t distract you from the genius of its compositions and arrangements. Hayes’ creativity and imagination shows its full range here—from the ominous funk of the hit title track to the breezy Wes Montgomery-style jazz groove of “Cafe Regio’s.” The horn section is used to powerful effect, and it is seldomly in quite the way you would expect: the horns play the punctuating role of the keyboardist’s left hand, a flute takes the high notes on top of the brass section, or a single trumpet plays in unison with the low end of a guitar. The title track opened up the evocative possibilities for R&B music, something the Temptations would pick up on a year later with “Papa Was a Rolling Stone.” Plus, eternal blessings to Hayes for making the wah-wah rhythm guitar and those 16th notes on the closed high-hat cymbal one of the iconic sounds of the ‘70s. The sound is forever attached to its era, but it has lost none of its funkiness or drive 50 years later. You can listen to Shaft as the soundtrack to a badass movie. Or you can free yourself of that limiting context and hear it as a kind of Black Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, bursting with ambition, melodicism, imagination, range, and musicianship.

Pro-tip: if you ever see this album in a second-hand record store, take it to the counter, tell the clerk to play the near-seamless side four, and bet a dollar that someone will buy it right off the turntable. It’s worked for me twice.

–Allen Michie

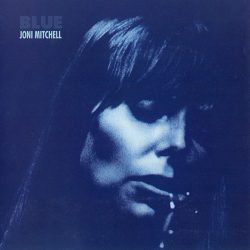

- Joni Mitchell: Blue (Reprise)

I was 15 in 1968 when I first encountered Joni Mitchell. I would listen to WNEW-FM in New York on my bedside radio late at night as the dulcet voice of Alison Steele, the Nightbird, would introduce new artists like James Taylor, Laura Nyro, and Crosby, Stills & Nash. I wore out Mitchell’s early albums, and I fell in love with the image of that innocent blonde beauty whose voice and music touched my nascent romantic soul. When Blue was released, just days after I graduated from high school in June, 1971, there was no doubt that this was an artist who had taken her artistry to another level. Her first three albums, Song to a Seagull, Clouds, and Ladies of the Canyon, had announced the emergence of a unique singer/songwriter. But Blue was a declarative statement, establishing Mitchell’s ability to mine a deeper vein of both musical and lyrical self-expression. The evocative dulcimer-laden songs, including “A Case of You,” “California, River,” “Carey,” and “All I Want,” flowed together in melancholy perfection. But there were no weak links; this was a sublime compendium that would undoubtedly define her career. With the likes of Stephen Stills, James Taylor, and Russ Kunkel accompanying her in the studio, Mitchell delivered a technically crisp and innovative performance. Despite her remarkable body of work, which has spanned several decades, Blue remains Michell’s signature album, the one that teary-eyed college students embraced as their angst-filled anthem, turning yearning into an art form.

I was 15 in 1968 when I first encountered Joni Mitchell. I would listen to WNEW-FM in New York on my bedside radio late at night as the dulcet voice of Alison Steele, the Nightbird, would introduce new artists like James Taylor, Laura Nyro, and Crosby, Stills & Nash. I wore out Mitchell’s early albums, and I fell in love with the image of that innocent blonde beauty whose voice and music touched my nascent romantic soul. When Blue was released, just days after I graduated from high school in June, 1971, there was no doubt that this was an artist who had taken her artistry to another level. Her first three albums, Song to a Seagull, Clouds, and Ladies of the Canyon, had announced the emergence of a unique singer/songwriter. But Blue was a declarative statement, establishing Mitchell’s ability to mine a deeper vein of both musical and lyrical self-expression. The evocative dulcimer-laden songs, including “A Case of You,” “California, River,” “Carey,” and “All I Want,” flowed together in melancholy perfection. But there were no weak links; this was a sublime compendium that would undoubtedly define her career. With the likes of Stephen Stills, James Taylor, and Russ Kunkel accompanying her in the studio, Mitchell delivered a technically crisp and innovative performance. Despite her remarkable body of work, which has spanned several decades, Blue remains Michell’s signature album, the one that teary-eyed college students embraced as their angst-filled anthem, turning yearning into an art form.

–Glenn Rifkin

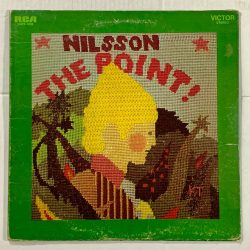

- Harry Nilsson: The Point! (RCA Victor)

I first heard The Point! in 1987, when I was a melancholy fourth-grade misfit. Harry Nilsson’s parable of the round-headed Oblio, growing up in a town where all the people were born with points on the tops of their heads, mirrored my feelings of alienation from my affluent classmates and the bedroom community where my family was living. Nilsson’s hero’s-journey-for-kids fable and witty, non-preachy narration is delivered in a rumbling spoken baritone by the singer himself, complete with stumbles, hesitations, and page-turning sounds left in. It was infectious, and the music stayed with me long after I graduated from high school. The melodies split the difference between catchy and surprising. Nilsson’s production and George Tipton’s orchestrations gave the music an almost tactile quality. The singer’s humming and scatting over the instrumental break in “Everything’s Got ‘Em” sounds like a stone skipping across a stream. Hints of Nilsson’s ribaldry sneak through the otherwise kid-friendly perspective, making The Point! the rare children’s album with a song about drunk-dialing your ex (“POV Waltz”). With its inventive arrangements, whimsical songs, and wry humor, The Point! is an album for elementary-school outsiders of all ages.

I first heard The Point! in 1987, when I was a melancholy fourth-grade misfit. Harry Nilsson’s parable of the round-headed Oblio, growing up in a town where all the people were born with points on the tops of their heads, mirrored my feelings of alienation from my affluent classmates and the bedroom community where my family was living. Nilsson’s hero’s-journey-for-kids fable and witty, non-preachy narration is delivered in a rumbling spoken baritone by the singer himself, complete with stumbles, hesitations, and page-turning sounds left in. It was infectious, and the music stayed with me long after I graduated from high school. The melodies split the difference between catchy and surprising. Nilsson’s production and George Tipton’s orchestrations gave the music an almost tactile quality. The singer’s humming and scatting over the instrumental break in “Everything’s Got ‘Em” sounds like a stone skipping across a stream. Hints of Nilsson’s ribaldry sneak through the otherwise kid-friendly perspective, making The Point! the rare children’s album with a song about drunk-dialing your ex (“POV Waltz”). With its inventive arrangements, whimsical songs, and wry humor, The Point! is an album for elementary-school outsiders of all ages.

–Chelsea Spear

Tagged: "Shaft”: Music from the Soundtrack, Blue, Harry Nilsson, Isaac Hayes, Janice Joplin, oni Mitchell, Pearl, The Point!

Regarding Weather Report’s remarkable 1st album (50 yrsago?!), Steve Elman mentions “open, modal harmonies”…? What does that mean? ‘Modal’, ok, yes, we always hear that in references to Miles Davis & John Coltrane…but ‘open’?

Good catch! The phrase should have been “modal harmonies and open structures,” and I’ve made the change in the text. Many thanks.

Loved the “Blue” review by Glenn Rifkin. I not only agree (like many do) with the critical opinion that “Ble” was and still is the high-point of Mitchell’s long career, but the elevation of yearning, melancholy and poetic perception hit a songwriting peak with “Blue” that has not been equaled since. It was an album truly greater than the sum of it’s marvelous parts. A long time ago, I mentioned to a rocker friend of mine that Joni Mitchell was my feminine ideal. He said with a scowl: “Do you really want all theat goddamn butterscotch streaming through your kitchen window every morning?” It was a witty reference to a youthful upbeat lyric from the “Ladies of the Canyon” LP.

I simply replied. “Yes, I do.” But with “Blue’s” darker hues, even the leather-clad rockers of 1971 were in love with Joni.

[…] this be a case of reviewer envy? After seeing the magazine’s music critics pay monthly homage to 1971 as a monumental year for music, the Arts Fuse‘s film critics immediately registered — […]

This just in about Joni Mitchell’s “Blue”:

https://www.msn.com/en-us/music/news/joni-mitchell-releases-blue-50-with-outtakes-and-unreleased-tracks-from-1971-classic/ar-AALh4sP?ocid=winp1taskbar

Here’s another 50th anniversary apprecation of Isaac Hayes’ “Shaft” soundtrack:

https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/isaac-hayes-shaft-reinvented-game-162333553.html