Flipping a Coin: The Significance of Anna May Wong’s Quarter

By John Barrett

What emerges from even a cursory study of Anna May Wong’s life is that her complexity and depth were rarely acknowledged but she used her intelligence to control the narrative as much as she could.

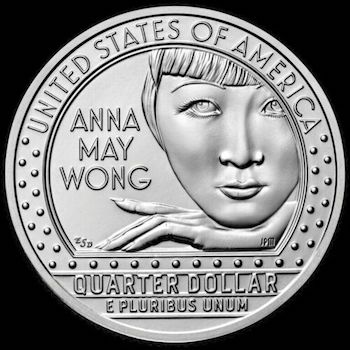

In October of last year, the US Mint released a quarter bearing the face of Anna May Wong — widely acknowledged as the first Chinese-American movie star — as part of its American Women Quarters initiative. The program recognizes the pioneering contributions of women in technology, science, and the arts. For some, however, there is a sense that the posthumous honor comes as a “mea culpa.” Even so, I think it is important to shift the narrative a bit. I would rather see Wong’s recognition more as a belated victory and less as a cultural afterthought.

In October of last year, the US Mint released a quarter bearing the face of Anna May Wong — widely acknowledged as the first Chinese-American movie star — as part of its American Women Quarters initiative. The program recognizes the pioneering contributions of women in technology, science, and the arts. For some, however, there is a sense that the posthumous honor comes as a “mea culpa.” Even so, I think it is important to shift the narrative a bit. I would rather see Wong’s recognition more as a belated victory and less as a cultural afterthought.

No small amount of verbiage has been spent on framing Wong almost exclusively as a victim of racism and orientalist objectification. It would be foolish to deny that those elements loomed large (and continue to); however, I think it is worthwhile to celebrate what she did accomplish — as a performer, a woman, and a cultural icon; as what we would call an activist; and as what she might call a woman speaking her mind.

It has been debated just how meaningful her contributions have been to opening doors to Asian Pacific Americans and, by extension, greater diversity in the arts. Some argue that her effect on the studios was minimal, if not nil, and that too little has changed in the years since her heyday or her death. In the oddly insultingly titled biography Tool of the Sea, Jennifer Warner comments, “Her legacy was not that she had broken down racial barriers or changed prejudices, but that her career existed at all.” I would argue that the fact that Wong’s career “existed at all” was pivotal. Her perseverance for over two decades in film and a late career foray into television moved the needle forward in progressive representation.

That representation, of course, had its limits. She was routinely denied starring roles and parts where she “got the guy” (let alone was able to kiss him onscreen). Even when she played the heroine of the story, she was doomed to die. Her later films at Paramount provided Wong with (perhaps) more sympathetic characters, but she was passed over for what should have been the defining role of her career, as O-lan, the heroine of the 1937 screen adaptation of Pearl Buck’s wildly successful novel The Good Earth. The German-born Luise Rainer played O-lan in “yellowface,” and won an Oscar for her performance. (As consolation, the studio offered Wong the opportunity to read for the second wife in the story, who winds up ruining the family). This was not the first snub; she had been dropped from The Son-Daughter (1933) in favor of Helen Hayes.

Even considering such setbacks, though, Anna May Wong was able to maintain a presence (and a well-regarded one, at that) during the height of her Hollywood career, from the late 1920s to the mid-1930s. She was still not getting roles worthy of her, but she remained a high-profile representative for Chinese Americans and her presence contributed to greater representation for other actors of Asian descent over the coming decades.

This is not to say that Wong’s stardom was necessarily welcomed by either the Chinese American community, Chinese people in what was then the Republic of China, the Chinese Nationalist Government, or for that matter, her own family. Indeed, she was excoriated for damaging the image of Chinese people both in the US and in China, both for simply being an actress and even where that was accepted, criticized for playing women of dubious or low character, which in turn was considered to reflect badly on China and Chinese people.

Nevertheless, what emerges from even a cursory study of Wong’s life is a woman of complexity and depth that were rarely acknowledged, who used her intelligence to control the narrative as much as she could. She actively participated in crafting her image; recognizing that staying in Hollywood would ultimately lead to ghettoization and stagnation, she left in 1928 to work in Europe, which not only elevated her prospects for better dramatic material but also expanded her recognition as an international cosmopolitan figure.

Anna May Wong in the 1929 silent film Piccadilly.

Those years spent filming and performing on stage in Germany, France, and England said as much about prejudice and exclusion in the United States as it did about legitimizing Wong’s talents. She was in good company: Josephine Baker, Paul Robeson, Langston Hughes, and others luxuriated in an air that was easier to breathe. The price was varying degrees of exoticism that would surely grate, but it was a price worth paying rather than suffering increasing marginalization in your chosen field and exclusion from the greater society of the nation of which you were a citizen.

Certainly, after her return to the US in 1931 (she would return to Europe periodically over the next two years) and the rise of critical acclaim stemming in large part from her performance in Josef von Sternberg’s Shanghai Express opposite Marlene Dietrich, her impact on the cultural consciousness would have been hard to deny. Moreover, some of her roles now were smart women surviving by their wits and played as such, with no pidgin English to diminish her own or her character’s stature. Even in roles that are little more than walk-ons, Wong lent a presence to characters who would have made far less of an impact in other hands (I have in mind her turn as an accomplice to murder and fraud in 1933’s A Study in Scarlet, but you could insert just about any role where her appearance was minimal but pivotal to the story).

As much as Anna May Wong’s contribution to Asian and Asian American representation and greater inclusivity can and should be framed more positively, it was limited by the intensity of the racism, tokenism, and eventual dismissal that she encountered in her life and career.

Partly as a response to this, in 1936 Wong traveled to China, both to inquire into her origins and to reassert her cosmopolitan transnationalism. Her 10-month visit resulted in a documentary she produced, which was filmed professionally and released on television 20 years later with her own narration. Her stated desire was to find her roots, but she also admitted that she had reservations about how she and her project would be received. This wariness is understandable, given her reception by the Nationalist government years earlier

Anna May Wong and Philip Ahn in 1937’s Daughter of Shanghai.

Wong’s travels in China and the resulting film, along with dispatches she wrote for the New York Herald Tribune, were crucial to her career because they heightened her visibility. More important, she came away with a deeper sense of self. Shirley Lim, author of Anna May Wong: Performing the Modern, sees Wong’s self-produced film as a reflection of her inner growth and maturation.

Upon returning to the States, Wong secured a four-picture contract with Paramount, playing savvy, brave, women in what were very much “B” movies. She may have had misgivings about the artistic quality of those films, but she was confident by then that she would be representing herself and her community in a considerably more positive light than her earlier roles.

Rewatching Daughter of Shanghai and King of Chinatown now, I’m struck by how deftly Wong reclaims the “Chinese detective” trope from the Swedish-American Warner Oland as Charlie Chan or the English Boris Karloff as Mr. Wong. She ratchets it up a notch because she’s a woman. None of the Paramount films are by any stretch “bad” — they are solid entertainment. Their significance lies in what they mean to a marginalized community. Today we hear quite a bit from underrepresented communities about how important it is that they be seen; something similar may have crossed the minds of Asian Americans in the ’30s who saw a smart, articulate woman representing them in what were traditionally Caucasian-led genre flicks.

As Wong turned her energies more to activism on China’s relief and other areas of the war effort, her output dwindled. Even then, though, she tried to make movies that would count. Her last two filmed during World War II — Lady from Chungking and Bombs Over Burma — gave her two more heroic leads as well as salaries that she would donate to China relief efforts.

Anna May Wong and Barbara Stanwyck on TV’s The Barbara Stanwyck Show.

Predictably, roles evaporated during the war when Wong became a woman of a “certain age” (in her late 30s at the beginning of the war and turning 40 by its end). To her credit, Wong was ahead of the patriarchal curve in that regard. She took pains to invest in real estate before the inevitable fickleness of Hollywood struck. She developed the apartments she had purchased and, apparently, took care of her siblings. She did not return to the screen until 1949’s Impact, and would not return to a feature film for another 11 years.

What she would do is launch the first Asian American–helmed television series for the Dumont Network, The Gallery of Madam Liu-Tsong, which was canceled after 10 episodes in 1951 (Dumont would shut down in 1956). Madame Liu-Tsong (Anna May’s Chinese given name) was the owner of a worldwide collection of art galleries who solved crimes. Unfortunately, nothing of the series survives; the Dumont kinescopes are literally lying on the floor of New York Harbor.

Nonetheless, Wong continued to work extensively in the new medium of television. She even scored a belated triumph by appearing as the Other Woman (the wronged “Chinese Wife,” in the teleplay) in a small-screen adaptation of William Wyler’s The Letter (playing a role she had been passed over for in Wyler’s earlier feature).

A small role in the Lana Turner film Portrait in Black was significant enough to help her land a strong supporting part in Flower Drum Song, based on the musical’s book by Oscar Hammerstein, itself based on C.Y. Lee’s novel. Sadly, Anna May Wong died in early 1961 before filming began. That she was highly regarded enough to appear in supporting roles (admittedly, most unworthy of what she could deliver) into the ’50s is telling. That her role in Portrait in Black made enough of an impression for her to be afforded a film “comeback” only compounds the tragedy of her death at 56.

How would she have felt about Mickey Rooney’s portrayal of a Japanese character in Breakfast at Tiffany’s? Or Peter Sellers as Fu Manchu? Would she shake her head at Scarlett Johansson’s portrayal of the Major in the live action Ghost in a Shell or Emma Stone’s turn as a half-Chinese, half-Hawaiian woman in Cameron Crowe’s Aloha (the epitome of WTF-ery if ever there were one)? The film industry still has a long way to go in terms of representation. Had she lived longer, I think Wong would have been outspoken enough to take the appropriate parties to task.

It would be absurd to conclude that the mere existence of an Anna May Wong or her filmography addressed, let alone rectified, the systemic racism that is a significant and painful part of this country’s DNA. But that her career existed at all, that she was able to say “I protest,” is worthy at the very least of coinage. That she deserves more has only grown more apparent in recent years.

Note: A handful of Anna May Wong’s films are on streaming services like Amazon Prime. However, over half of her filmography has passed into public domain and may be found at the Internet Archive (Archive.org) or on YouTube. There is a curated collection of many of her features, short subjects, and even television plays on the “The Gallery of Anna May Wong” channel: https://youtube.com/@thegalleryofannamaywong.

John Barrett is a painter, printmaker, writer living (for the moment, anyway) in Houston, TX. He is definitely looking forward to returning to New England in the near future and back to Asia later this year. He has written for the Somerville News, Tai Chi magazine, and random joints here and there. Like everyone else in this world, he maintains his own little bit of the internet at Reaction Shots.

Hi Mr. Barrett,

My name is Anna Wong & I am AMW’s niece. I can confirm my aunt did support her siblings. Her apartment complex in Santa Monica named Moongate was one of her most prized possessions.

Thank you for a well written article

Ms. Wong! It’s an honor to hear from you. I was actually working on what might yet turn into a series on your esteemed aunt’s filmography. And then, when the US Mint announced the release of the quarter, all I could say was “Kismet”!

I was happy to write this (and thanks to Bill Marx and Evelyn Rosenthal for their editing/sculpting skill). AMW is owed so much more and I suspect there is more to come. Hodges’ biography and the work done by Shirley Lim and Karen Leong has set the bar high.

I think a deeper analysis into how important her family was to her is merited for filling out more of who she was as a person. I also hope that some of her dispatches from her time in China, other articles and “I Protest” eventually find their way into an anthology.

Thank you for your confirmation and kind words,

John

I just found one of these in my palm before putting it in the coin slot and immediately stopped it caught my eye like crazy and I saved it and will continue to save it. It looks very special.

I just found one of these in my hand, and I thought the same thing. It looks like a very special quarter. Keeping this one!

John, I enjoyed your article immensely.

Anna May was able to express a great range of emotions in silent films, all the way back to “Dinty” in 1920 and able to do so without overacting.

In “Piccadilly”, the “kiss” with the male lead is clipped just before their lips touched. She was furious that censors clipped part of a well thought out and dramatic scene. But there is no doubt the sparks were flying. Her acting is great-Jameson Thomas as the male lead good, but no more.

However, it is the disdain, fury, and dignity she brings to bear against the scatter-brained Gilda Gray in the next scene where she displays her real acting skill. Gray treats Sho Sho like a child-a naive and limited little Chinese girl. Wong’s literal stature belies the insult.

There are some inter-titles. But you don’t really need them to know that Sho Sho is assertively and correctly telling Valentine’s ex-lover that she is more than a match, more of a woman, and superior in every way to Gray that is the point. And it is kind of a big deal.

After a furious storm of perfectly silent words, Sho Sho’s inter-title makes the point: “I want him, and I shall keep him!”

There is much of that in “Shanghai Express”. Hui Fei is a prostitute, not a door mat. She is entitled to seek justice for the personal injury of rape, but also for the insult to her dignity. She saves, in many ways, everyone on the train.

But she does so for her justice, not their benefit. And she will not accept the praise for the “brave little Chinese girl” from those who help her contempt an hour earlier.

The way she performs the role of Hui Fei, I would say, makes her the first true female Anti-Hero in sound film.

I doubt that less than 10% of Americans know who Anna May Wong is/ was !! I feel there are a large # of notable American Females who would be a MUCH BETTER CHOICE 2 B featured on our quarter or any of our currancy. SHAME ON WHO EVER MADE THIS DECISION !!!!!!!!

MI Carroll seems upset by the issuing of a coin honoring the achievements and memory of Anna May Wong, whose life and accomplishments has steadily come back into focus over the past two decades. Apparently, Mr./Ms. Carroll may not have availed themselves to explore the American Women Quarter Program roll-out linked to in the article. Indeed, did Mr./Ms. Carroll actually read the article? I cannot tell.

The relevant link is here: https://www.usmint.gov/learn/coin-and-medal-programs/american-women-quarters/.

In any case, for Mr./Ms. Carroll’s (and others’) edification and convenience, here is a full list of the roll-out of all quarters to be issued by the United States Mint. I, for one, am grateful to the Mint and this initiative for bringing so many names that are new to me and expanding my appreciation of these women in all these areas of achievement. It is truly humbling.

2022

Maya Angelou – celebrated writer, performer, and social activist

Dr. Sally Ride – physicist, astronaut, educator, and first American woman in space

Wilma Mankiller – first woman elected principal chief of the Cherokee Nation

Nina Otero-Warren – suffrage leader and the first woman superintendent of Santa Fe public schools

Anna May Wong – first Chinese American film star in Hollywood

2023

Bessie Coleman – first African American and first Native American woman pilot

Edith Kanakaʻole – indigenous Hawaiian composer, custodian of native culture and traditions

Eleanor Roosevelt – first lady, author, and civil liberties advocate

Jovita Idar – Mexican-American journalist, activist, teacher, and suffragist

Maria Tallchief – America’s first prima ballerina

2024

Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray – poet, writer, activist, lawyer, and Episcopal priest

Patsy Takemoto Mink – first woman of color to serve in Congress

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker – Civil War surgeon, women’s rights advocate, and abolitionist

Celia Cruz – Cuban-American singer, cultural icon, and one of the most popular Latin artists of the 20th century

Zitkala-Ša – writer, composer, educator, and political activist

Glad to hear you liked the article, Tom, and thank you for comment. Piccadilly is a treat, for sure and I could go on at great length about her performance as Hui Fei, a truly great character.

It is heartening to see AMW getting her due and watching her rediscovery by new generations.

Why was the art for George Washington on these 2023 quarters altered to look more like a Native American than a founding father?

Because GW was facing to right, that I stopped and LOOKED at the coin! Then I questioned, “Who is Anna May Wong?”

After reading about her, I’m glad she is finally being recognized for her professional acting in movies that were NOT easy to produce. My Library contains EVERY Movie produced from Silent to Audio including the FIRST movies in the early 1900’s.

When I saw Anna May I knew I had watched her performances. She was beautiful. She was professional. She was an early movie star.

She deserves the honor of the quarter.

Hello Mr Barrett,

Thank you for your very interesting article on Anna May Wong. Not being American I had never heard of her until I started collecting the coins with her image and those of the other trailblazing American women. Coincidentally, I was given two Anna May Wong coins in my change at Whole Foods last night! Your article has brought to life a woman of great strength and character, and I thank you for it.

Rosalind Russell

Thanks for article explaining Anna Mae Wong’s contribution to acceptance of movie stars who don’t look like “white “ actors. I initially thought the coin was phony since I wasn’t aware of the special series honoring women. I might have discarded the coin as a phony if not for finding your article.

John:

Fascinating summary of AMW and her career. You cover all the bases nicely.

She was indeed a ‘cosmopolitan transnational’ and is finally starting to get her due. First this coin, then a Barbie Doll by Mattel and now her first museum exhibition.

My collection of original lobby cards featuring her will be on exhibition at the San Diego Chinese Historical Museum March 1 thru 10, 2024.

Hope you can swing by and in person. The exhibition is curated by Katie Gee Salisbury whose new book NOT YOUR CHINA DOLL will be out very soon.

Dwight Cleveland

What was the impact of Anna May Wong’s self-produced documentary and her travels in China on her career and visibility?