Book Review: Vincent Czyz’s “Sun Eye Moon Eye” — Cozy with the Quotidian and the Cosmological

By Gary Lippman

Logan Blackfeather is such a marvelous hero — and he is, in most senses of the word, heroic — that most readers will quickly connect with him and happily trail him through the significant stages of his education.

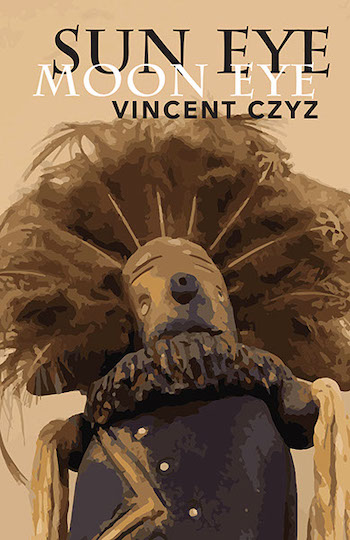

Sun Eye Moon Eye by Vincent Czyz. Spuyten Duyvil, 588 pages, $25.

A divine bouncer with a burning pool cue tossed us out of the Paradise Lounge, and we’ve been drinking ourselves into oblivion ever since. Forgetfulness ain’t quite bliss, doesn’t quite replace ignorance, but it’ll do in a pinch. It’s a lot easier than trying to follow some eight-fold origami path to get to a dry establishment called the Enlightenment Inn.

This buoyant metaphor almost never reached the reading public; it appears in a superb novel that did not find a home for thirty-two years. Vincent Czyz, a New Jersey–based author (and occasional contributor to The Arts Fuse), began shopping around the manuscript in 1991, but its considerable length and its rewarding yet somewhat challenging visionary qualities failed to appeal to mainstream publishers, whose sights, as ever, are fixed on profitable beach reads.

This buoyant metaphor almost never reached the reading public; it appears in a superb novel that did not find a home for thirty-two years. Vincent Czyz, a New Jersey–based author (and occasional contributor to The Arts Fuse), began shopping around the manuscript in 1991, but its considerable length and its rewarding yet somewhat challenging visionary qualities failed to appeal to mainstream publishers, whose sights, as ever, are fixed on profitable beach reads.

Czyz went on writing, however, releasing uniformly fine work — a book of short fiction, a novel, a novella, an essay collection — while the first opus, titled Sun Eye Moon Eye, remained on the proverbial shelf. Until now, that is. Fortunately, Spuyten Duyvil has published Czyz’s novel, and the experience of reading the book, pondering its mysteries and savoring its power, feels timeless.

Sun Eye Moon Eye is essentially a bildungsroman, the story of an artist’s personal development, but there’s little that’s predictable about it. Profound strangeness follows its protagonist, one Logan Blackfeather, as he mindfully zigs and zags all over the American map. Make that maps, because Blackfeather travels not just the geographical one but those of his head and heart and spirit.

At the start of the story, in the 1980s, this half-Hopi and half-Anglo young musician is wandering through the Arizona desert enduring the aftermath of a spiritual quest after an amiable stranger drives him to a roadside tavern called The Smiling Aztec. (In a typically piquant observation, Czyz writes that the stranger’s talkativeness was “like a light rain” that Blackfeather “didn’t bother to get out of.”)

Romance appears to be imminent until an act of fatal violence lands the protagonist in a psychiatric hospital in rural New York. After his stint in “Upstate University,” as Blackfeather calls it, he winds up in the punk rock clubs, art galleries, and wealthy mansions of Manhattan, where romance — of the Downtown variety — finally arrives. This time with Shawna, an enticing but complicated young woman.

The affair, complete with all the self-protective emotional feints, misunderstandings, brave expressions of vulnerability, and strenuous sex that distinguish early love, are well-rendered by Czyz, who even manages to make an erotic threesome as believable as it is lyrical (and off-the-charts sexy). He’s equally proficient with the push-and-pull of male-to-male friendships and the doctor-patient struggles of psychotherapy. Meanwhile, the suicide of a lovably quirky lover, whom Blackfeather met (and abandoned) in the psychiatric hospital, makes for one of the novel’s most heartbreaking sequences:

Silently he asked Linda to forgive him. For letting her wade out into an emotion he couldn’t return. For being in love with being able to walk and listen and breathe. He had no doubt that the Earth, which had taken her back, had a soul too, something you might hear rustling among stalks of wheat where even a crow could see that a paralyzed farmer, leaking straw, lacked the breath moving through the field.

Apart from romance, the most intimate relationships in Sun Eye Moon Eye revolve around the protagonist’s three male ancestors. First, there is Blackfeather’s grandfather, who serves as a guiding force of Hopi tradition and wisdom. Next is Blackfeather’s father, who died in an automobile accident (or was it an accident?) during the protagonist’s childhood. The dead man’s ghost (perhaps literal, perhaps not) appears wordlessly to Blackfeather throughout the narrative in vividly described scenes. Finally, there is Blackfeather’s uncle, who also becomes his stepfather, a malevolent figure whose cruelty increasingly impels the now-fatherless (and passively mothered) boy to define himself as a man.

Although each of these ancestor figures could be viewed as familiar archetypes in a coming-of-age saga, Czyz utilizes them in creatively subversive ways. Blackfeather’s grandfather is long gone, his lessons incompletely remembered, while the reckoning scene with the evil stepfather takes an utterly unexpected — even shocking– turn that makes for one of the book’s most effective scenes. Also unexpected, and unforgettable, is Blackfeather’s final encounter with his father’s ghost:

Logan watched him twist the cap off the beer bottle—quite a feat for a man who’d been dead for 18 years—his eye keen on the subtle interplay of bones beneath the skin, the vein that seemed to wiggle across the back of his hand. Everything his father did, every sound that came from him—his voice, the groan of the chair under his weight, the rustle of his clothing—was miraculous. Logan wanted to put his hand next to his father’s mouth and feel the heat of his breath. He wanted to smell on it the last thing his father had eaten. Wanted to see his father swat a mosquito, see the bead of drawn blood and know that his father was still vulnerable to the thousand shocks flesh was heir to.

As this excerpt suggests, one of Czyz’s principal artistic gifts is his sensitivity with language. Nearly each page of Sun Eye Moon Eye brims over with gorgeous descriptions of people, places, and things — the abstract and the imaginary as well as the actual. Has the late 20th Century East Village Bohemia ever been as thrillingly depicted as it is here? Then there is the ocean:

He tried to understand how something so vast, so old and alive, hadn’t kept him awake at night with its far-off voice. Hadn’t added to the erosion of sleep even though he was in the middle of the continent, hadn’t pounded his complacency into granules he could’ve spread until he had a dry beach. He’d seen plains [in Kansas] rolling toward the curve of the Earth, but he’d never taken in anything of this magnitude that was moving…

Another gift that Czyz possesses in abundance is his sensitive, but unsentimental, insights into his characters’ motivations, ruminations, and behavior — especially, of course, those of his protagonist. Following Blackfeather’s journey, the reader may not always sympathize with the character, much less fully comprehend him. But the novel’s deep dive into his consciousness, as well as the unconscious storm systems that guide that consciousness, is never less than compelling.

Author Vincent Czyz. Photo: courtesy of the author

Native American culture heroes play a large part in Blackfeather’s psyche. But so do Osiris and Orpheus — as well as anonymous sages from street corners and pool halls. “As above, so below” goes a well-known alchemical credo, and Czyz is as cozy with the quotidian as he is with the cosmological. Consider this passage about a friend of Blackfeather’s who is passing a typical night in a favorite barroom:

If forced to choose, would he take another line of poetry or a line of coke? A little sky scanning or another gander from his bar-stool outpost at the sweaty faces and smoky voices?[…] Light chases the mystery outa things though pure darkness makes the exact whereabouts a your hand in fronta your face fairly enigmatic. A Beethoven symphony or the endless nightchant of insects in the fields? The Epic of Gilgamesh or another excursion to one of Pittsburgh’s titty bars? A little more living or a peek at the secrets of the dead?

So Sun Eye Moon Eye has charm to spare. A nasty sense of humor at times, too. But what really lifts the narrative into the stratosphere is its philosophical vision, intervals in which the author meticulously explores universal territories (with recreational drugs usually not a factor): “Memory is a city like St. Louis piled along the flow of night,” Czyz writes, “twinkling from a distance as it’s carried downriver, lost in a heartland flooded black—a flat-out sprawl somewhere below the threshold of notice waiting for a switch to be flicked on, a star to go nova.”

Czyz wrings his most frequent metaphysical variations out of the motif that gives his novel its title:

We’re a bit like a god whose one eye is the Moon and the other, the Sun. Vision blending somewhere at the back of the skull. The moon eye saw in grainy black and white, the sun eye in color, with clarity. The moon eye was at home in a netherworld where only the shadow of the ordinary fell. The sun eye followed every line and angle, every contour, was fascinated by shape’s lovely demise—a melting candle, say.

And the upshot of this dichotomy becomes obvious: “Neither moon eye nor sun eye should hog the sky.”

At times, Czyz travels so deeply into esoteric realms that some readers might be puzzled. And at times the ornate language and concepts slow up plot momentum and payoffs. Still, no one picking up Sun Eye Moon Eye should mistake it for a beach read — it’s an ambitious and bold work of literature. Czyz depends on elevated language, and other elevated aspects, to accomplish his goals.

Besides, Logan Blackfeather is such a marvelous hero — and he is, in most senses of the word, heroic — that most readers will quickly connect with him and happily trail him through the significant stages of his education.

This being 2024, a portion of Czyz’s audience might question whether the author, a non-Native American, is aesthetically authorized to write a novel about a partly Hopi person. One answer to this can be found in Sun Eye Moon Eye itself, where Czyz writes about a “bespectacled old Hopi” who’s sitting atop a mesa that is “poking up into a dusty sky filled with silence.”

Would the mesa always find another people? Maybe. But not a people whose prayers would spill down its sides like runoff, shape it like wind, raise it up to scrape against the swirly edge of a nebula. Chance and luck, disguised as the favor of the gods (rain an overflow of divine gratitude), held a place in the villages. Fear of extinction had kept the ceremonies pure, harsh equation though that entailed.

Czyz’s depiction of this man on this mesa could have been written by prominent Native American writers such as Tommy Orange or Leslie Marmo Silko or N. Scott Momaday — or Czyz’s passage could have been penned by R.A. Lafferty or Thomas Sanchez, the Anglo scribes whose Okli Hannali (published in 1972) and Rabbit Boss (1973), respectively, are among our best novels about Indian civilization. The point is that fine art may, and should, be produced by anyone who wants to; and it may, and should, be enjoyed by anyone who willingly partakes of it. If one accepts those precepts, then it stands to reason that the imagination must not be subject to any culturally imposed purity tests.

“Humans,” opines Shawna, “are the saddest of all things … able to freely envision angelic beings but never to become one.” There’s little we can do about this predicament, of course — except perhaps to dance, as the author suggests in a refrain that echoes throughout Sun Eye Moon Eye: “Above all, he must run. Must Dance. And not stop dancing.” This simple wisdom benefits bott Blackfeather and Shawna, and it has clearly fortified the author himself, whose literary “dancing” all those years ago has at last paid off. May he keep making his words and his ideas dance, and continue to share them with sophisticated readers.

Gary Lippman, a recovering attorney, has published a novel, Set The Controls For The Heart Of Sharon Tate; a story collection, We Loved The World But Could Not Stay; the introduction to The Many Worlds Of David Amram; various Fodors travel guides; and essays that have appeared in the New York Times, the Paris Review, VICE, and Literary Hub. His play Paradox Lust was produced off-Broadway in 2001.

How does Czyz navigate the exploration of Native American culture and spirituality through the character of Logan Blackfeather, given the author’s own background?

“Blackfeather” the hero of the Novel seems to be my “Sorta o’ Man.” I’m just feeling him as I read through the aforementioned review, and brief synopsis. I can’t give you an honest “Why” at this time. But I’m sure that I will have more to say about him once I order the Novel and do a complete read through. And I will be ordering it very shortly. Indeed.

A good question. One answer might be to say the same way a Native American would navigate the difficulties of an Anglo protagonist. More specifically, though, aside from having visited the Hopi mesas (entirely inside the Navajo reservation) and a having done a good deal of research, I was careful not make Logan a full-blooded Hopi raised on the mesas. He doesn’t even grow up in Arizona, where the mesas are located. He is raised white in rural Kansas. So his connection to tribal Hopi, as I show in one particular chapter of the novel, is quite tenuous. Something else, however, that I think is important to bear in mind is that cultural influence is not a one-way street. Native American author and musician Robert Mirabel (Taos Pueblo) makes this clear in his book Running Alone. Describing a Christmas ceremony held in a pueblo, he writes: “It wasn’t Christian and it wasn’t pagan. It was a new mode of living brought to us by a woman carried on the shoulders of faithful yet faithless [re: Christianity] pueblo men. She welcomed everyone one of all the races that populate this world to bring in the new season of celebration inside the ancient, new augmentation of pueblo walls.” Imagining the other has been the domain of shamans and artists for thousands of years (beginning as humans playing the roles of various animals). If we begin to question that, it won’t be long before we question male authors creating female protagonists, female authors presenting male protagonists, etc.