Arts Reconsideration: The 1971 Project — Celebrating a Great Year in Music (March Entry)

Here’s yet one more fantastic thing about it no longer being 2020: it’s now the 50th anniversary of the excellent music that premiered in 1971.

Once a month throughout 2021, the Arts Fuse is taking a look back at the music of 50 years ago: what became classic, what is worth a reappraisal, and what has been overlooked. This month our writers take on a wide variety of genres: country-rock, singer-songwriter, reggae, and two uncompromising heavy metal albums. This was the music that got people mellowed out, charged up, and on the dance floor in 1971. Let us know in the comments section if you listened to this music back then and what your related favorites of the year are today.

— For those who missed it, here is the February Entry

— Allen Michie has graduate degrees in English Literature from Oxford University and Emory University. He works in higher education administration in Austin, Texas (home of Armadillo World Headquarters, which was just getting fired up in 1971).

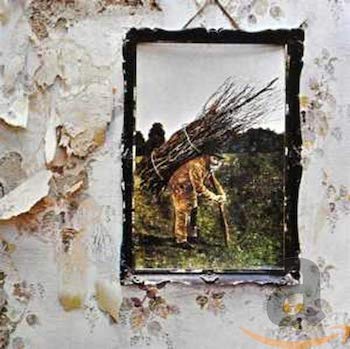

- Led Zeppelin: Led Zeppelin IV (Atlantic)

Between November 1, 1969, and February 28, 1970, the only two albums to sit atop the Billboard album chart were Abbey Road by the Beatles and Led Zeppelin’s II. Abbey Road was #1 for 11 of these 18 weeks, but II knocked the Fabs off their perch on three separate occasions, which is not nothing. Even more impressive, once Zeppelin grabbed the top spot at the end of January 1970, they kept it until the end of February, never allowing John, Paul, George, and Ringo to steal it back. Literally and figuratively, the ’60s were over, and the new decade would belong to the Mighty Zeppelin. It’s no surprise that Led Zeppelin II was such a massive success. The record was the band’s coming out party as it was the full realization of their heavy blues meets fantasy folk rock sound. It was only natural, then, that they followed it up in October 1970 with an album that was dominated by … acoustic guitars and traditional folk. History has been kind to Led Zeppelin III (honestly, it’s my favorite Zeppelin album), but at the time, fans and critics alike were nonplussed. So when it came time for the group’s next release, it was clear they would have to bring the rock. It’s to Zeppelin’s credit that it’s not all they brought.

Between November 1, 1969, and February 28, 1970, the only two albums to sit atop the Billboard album chart were Abbey Road by the Beatles and Led Zeppelin’s II. Abbey Road was #1 for 11 of these 18 weeks, but II knocked the Fabs off their perch on three separate occasions, which is not nothing. Even more impressive, once Zeppelin grabbed the top spot at the end of January 1970, they kept it until the end of February, never allowing John, Paul, George, and Ringo to steal it back. Literally and figuratively, the ’60s were over, and the new decade would belong to the Mighty Zeppelin. It’s no surprise that Led Zeppelin II was such a massive success. The record was the band’s coming out party as it was the full realization of their heavy blues meets fantasy folk rock sound. It was only natural, then, that they followed it up in October 1970 with an album that was dominated by … acoustic guitars and traditional folk. History has been kind to Led Zeppelin III (honestly, it’s my favorite Zeppelin album), but at the time, fans and critics alike were nonplussed. So when it came time for the group’s next release, it was clear they would have to bring the rock. It’s to Zeppelin’s credit that it’s not all they brought.

The band’s officially untitled fourth album (typically known as Led Zeppelin IV) combined everything everyone liked about II with everything everyone didn’t know they liked about III. The result was Zeppelin’s masterpiece. Side 1 opens with “Black Dog” and its iconic call and response between singer Robert Plant’s a cappella hey hey mamma vocals and guitarist Jimmy Page’s all-time monster riff (credit where due, bassist John Paul Jones actually wrote the riff). “Rock and Roll,” which begins with John Bonham drums lifted from a Little Richard song and features boogie-woogie piano from Rolling Stones right-hand man Ian Stewart, follows, making it very clear that Zeppelin have come to roar. Rock credentials reestablished, Page brings out a mandolin for the English folk-inspired “The Battle of Evermore,” and then stays in the acoustic vein with the gentle opening to the band’s most famous song, “Stairway to Heaven.” “Stairway,” of course, does not stay quiet, and over the span of its eight minutes, the tune builds and builds until it climaxes with one of Page’s most glorious solos and a signature Plant wail. The song is everything IV set out to be: folky and rocky, gentle and turbulent, quiet and loud. After these four songs, we could almost forgive Side 2 if it was an afterthought. But it isn’t. The side begins with the hippie palate cleanser “Misty Mountain Hop,” and then it transitions to the runaway train “Four Sticks.” Zeppelin next make their most obvious return to the sound of III with the Joni Mitchell-inspired “Going to California,” before closing the record with the heaviest blues they’d ever put to tape, a cover of Memphis Minnie’s “When the Levee Breaks.” There’s not a misstep on Side 2. In fact there’s not a misstep on the entire album. Led Zeppelin IV is a monster.

-Adam Ellsworth

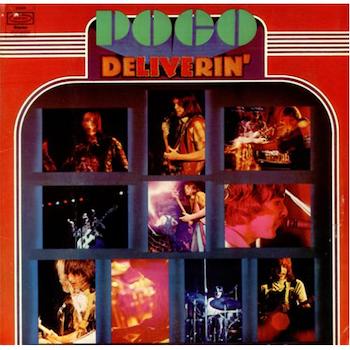

- Poco: Deliverin’ (Epic)

No band exhibited more yip-it-up glee and rambunctious, life-affirming joy than the L.A. country-rock quintet Poco. In 1971, Poco released their third album, Deliverin’, a live record, and an aesthetic and commercial success.

No band exhibited more yip-it-up glee and rambunctious, life-affirming joy than the L.A. country-rock quintet Poco. In 1971, Poco released their third album, Deliverin’, a live record, and an aesthetic and commercial success.

Poco has been long known as the “other group” that formed after the breakup of the extraordinary Buffalo Springfield. Stephen Stills and Neil Young formed Crosby, Stills, Nash &Young. Richie Furay and Jim Messina created Poco. The band’s other brush with rock fame is also a catty-corner affair: Randy Meisner and Timothy B. Schmidt both followed stints with Poco by joining The Eagles.

There is one other musician who cannot be ignored when discussing Poco: Rusty Young. The pedal steel guitarist has been the only member to perform with every permutation of Poco up to the present day. To date, Young has played with Poco for 52 years.

Poco was a beloved band, but never an overwhelmingly popular one. Their first two albums were commercial disappointments. Deliverin’ reached #26 on the pop charts. Their next few albums did far worse.

It was neither a paucity of talent nor bad luck that made Poco a second-tier band. Perhaps their country-rock genre was the issue: it was a style better loved by the critics than the public in 1971. Eclectic country-fusion acts (Linda Ronstadt, The Eagles, The Dead) enjoyed broader popularity. But the die-hard West Coast country-rock proponents — The Flying Burrito Brothers, The New Riders of the Purple Sage, even The Byrds’ Sweetheart of the Rodeo album — all failed to reach the Top 40.

Furay, as engaging a singer as he was a songwriter, quit Poco in 1973, reportedly depressed at the lack of widespread success. Yet Poco was a band with a significant concert following. Deliverin’ was recorded live in New York at Madison Square Garden’s Felt Forum and Boston’s Music Hall (now the Wang.) Both venues possess over 4,000 seats.

Crisply produced by Messina and powered by Young’s indefatigable pedal steel, the LP delivers a nearly unending spree of country-rock joy. The sound is fuller and more propulsive than their previous LPs. It is true that there is little emotional depth: Poco’s approach was nearly unrelentingly bright and cheery. Even a song about a wavering love affair, “You Better Think Twice,” rips it up with such untrammeled high spirits that it sounds downright triumphant

Hearing their signature song today — the incredibly catchy, infectious Pickin’ Up the Pieces — it’s baffling to realize it wasn’t even released as a single.

In an era when so many rock bands featured lengthy guitar and drum-drenched jams in their live shows, Poco followed a fresher method to goose up a set: the medley. And Poco’s bore no resemblance to the model greatest-hits throwaway medleys of the day. In Deliverin’, the two medleys are the album’s artistic highlights.

Poco’s unabashed enthusiasm was both a boon and a limitation. In the wake of such Californian darkness as the Altamont and Manson murders — and the havoc of Vietnam, Cambodia and Kent State — bright spirits were necessary. Poco was the nonpareil hippie feel-good band.

–Daniel Gewertz

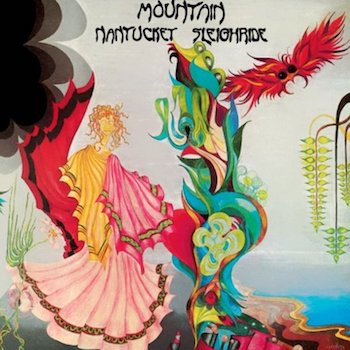

- Mountain, Nantucket Sleighride (Windfall)

Many of hard rock’s most epic tracks are about things you shouldn’t actually do: shooting heroin, chasing women, or in this case, hunting whales. Actually written on Nantucket (where co-leader Felix Pappalardi had a summer home), the title track to Nantucket Sleighride feels deep and ominous as outer New England, yet it rocks hard, with co-leader Leslie West slinging heavy riffs whenever the layered arrangement lets him. The lyrics, mainly by the late Gail Collins, have the gravitas of a classic folk song — “I know you’re the last true love I’ll ever meet,” the singer tells his partner — and the instrumental break swings majestically into a traditional Scottish tune (the title was a local term for what happens when a harpooned whale carries a boat to sea). As the ’70s went on, heavy metal and progressive rock would go into separate camps, but this is how it sounded before the boundaries were drawn.

Many of hard rock’s most epic tracks are about things you shouldn’t actually do: shooting heroin, chasing women, or in this case, hunting whales. Actually written on Nantucket (where co-leader Felix Pappalardi had a summer home), the title track to Nantucket Sleighride feels deep and ominous as outer New England, yet it rocks hard, with co-leader Leslie West slinging heavy riffs whenever the layered arrangement lets him. The lyrics, mainly by the late Gail Collins, have the gravitas of a classic folk song — “I know you’re the last true love I’ll ever meet,” the singer tells his partner — and the instrumental break swings majestically into a traditional Scottish tune (the title was a local term for what happens when a harpooned whale carries a boat to sea). As the ’70s went on, heavy metal and progressive rock would go into separate camps, but this is how it sounded before the boundaries were drawn.

The two bandleaders were an odd match from the start: West was a boisterous garage rocker who’d fronted Long Island bar band the Vagrants; Pappalardi was the whiz-kid producer of Cream and others. The Pappalardi/West dynamic made Mountain a band at cross-purposes: they wanted to be haunting and poetic, but they also wanted to boogie. And at a time when Hendrix and Cream were still a very fresh memory, those two impulses didn’t seem contradictory. So it works when “Don’t Look Around,” the album’s opener and toughest rocker, borrows the heady Mellotron textures that Pappalardi used on Cream’s “White Room.” Written as an elegy for Hendrix, the soft-then-hard shifts on “Tired Angels” embody the confusion of the time. Here we have a group who’d played Woodstock wondering if the dream was already over. It’s not all downcast, though: Pappalardi’s wistful “My Lady” is a love song without any Zeppelin chest-pounding. West’s song “The Animal Trainer and the Toad” is a Chuck Berry–styled telling of the friendship and the band’s history: “I’m in a band, a rock and roll band!” he shouts in a moment of pure bravado.

Mountain’s story didn’t end well: they broke up halfway through their next album, so Flowers of Evil came out with a studio side (on which the chosen topic, the heroin problem in Vietnam, sinks any joy the music had) and a much better live side. Various reunions didn’t fly, though versions of the band would keep going into the 2000s. The lady Pappalardi sang about, Gail Collins, shot him in 1976 in an apparent drug dispute. West survived multiple health problems before dying last December, leaving drummer Corky Laing as the band’s only survivor. But their greatest track endures; look out on the water in Nantucket and you can still hear it in the wind.

-Brett Milano

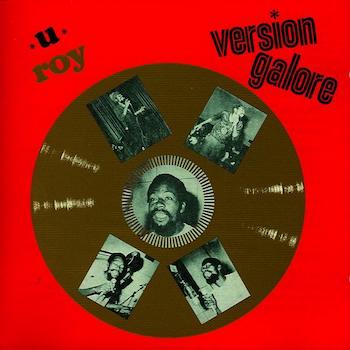

- U-Roy, Version Galore (Treasure Isle)

The liner notes for Version Galore caution that “U-Roy is not a singer, he plays no instruments. He just deejays.”

Talk about an understatement. Like with rock or blues or hip-hop, there’s no single originator of dancehall reggae, but there are towering pioneers. U-Roy’s status as one of dancehall’s godfathers was so undisputed that long before his passing last month, he was usually billed as “Daddy U-Roy.”

Talk about an understatement. Like with rock or blues or hip-hop, there’s no single originator of dancehall reggae, but there are towering pioneers. U-Roy’s status as one of dancehall’s godfathers was so undisputed that long before his passing last month, he was usually billed as “Daddy U-Roy.”

By toasting their often-improvised lyrics over previously recorded 45s to excite and please patrons at sound system dances, deejays like U-Roy set the stage for a musical revolution both at home and abroad—and that was even before figures like Jamaican-born, Bronx-bred Kool Herc developed hip-hop.

This album of “Versions galore, you can hear them by the score,” as U-Roy promises in the title track, consists of rocksteady tracks released on Duke Reid’s Treasure Isle label by the likes of vocalists the Melodians, the Paragons, Phyllis Dillon, and saxophonist Tommy McCook which were “versioned” when U-Roy toasted on top of them. (One of those Paragon cuts, “The Tide Is High,” would be famously covered by Blondie a decade later.) Although the album’s actual release date varies among online resources, the disc made its international impact in 1971 when the Trojan label issued it in the UK.

Throughout Version Galore, U-Roy takes his crown as boss deejay by proving himself an exciting stylist, whose trademark screams of “wah!” and “chick-a-bow!” were just as memorable as his actual catchphrases. It was a formula that guaranteed that long after the dance was over, U-Roy’s influence on global culture would remain incalculable.

-Noah Schaffer

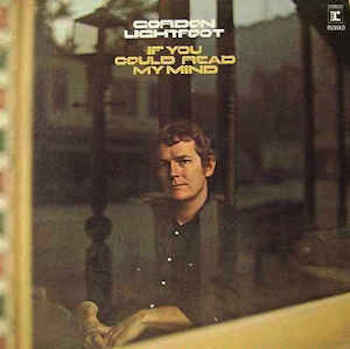

- Gordon Lightfoot, If You Could Read My Mind (a.k.a. Sit Down Young Stranger) (Reprise)

That voice. When I was 15 and brooding, it was that voice that spoke to me. Lilting, rich, smooth, singing of heartbreak and romance, it cut through the Top 40 that I listened to obsessively: “If you could read my mind love, what a tale my thoughts could tell… ” And I wanted to hear what Gordon Lightfoot could tell. Even though the album was released in 1970, the single was heavily in the charts in 1971. It was so popular that the album, originally titled after its folksy wanna-be hit single “Sit Down Young Stranger,” was renamed. The first single released from this was actually a cover of Kris Kristofferson’s “Me and Bobby McGee,” but it didn’t make a dent in the charts (just as well, because that song would belong to Janis Joplin in 1971 and forevermore). But “If You Could Read My Mind,” placed in an unassuming spot on the second side of the album (side placement meant something back in the day), took off.

That voice. When I was 15 and brooding, it was that voice that spoke to me. Lilting, rich, smooth, singing of heartbreak and romance, it cut through the Top 40 that I listened to obsessively: “If you could read my mind love, what a tale my thoughts could tell… ” And I wanted to hear what Gordon Lightfoot could tell. Even though the album was released in 1970, the single was heavily in the charts in 1971. It was so popular that the album, originally titled after its folksy wanna-be hit single “Sit Down Young Stranger,” was renamed. The first single released from this was actually a cover of Kris Kristofferson’s “Me and Bobby McGee,” but it didn’t make a dent in the charts (just as well, because that song would belong to Janis Joplin in 1971 and forevermore). But “If You Could Read My Mind,” placed in an unassuming spot on the second side of the album (side placement meant something back in the day), took off.

It was everywhere, that gorgeously arranged and lush piece of lyrical gold. It was irresistible. It’s been covered by everyone from Johnny Cash and Neil Young to Diana Krall, and there’s a disco version by Wendy Rivers. The album itself was a gem. It was a new start on a new label for Lightfoot, as he transitioned from popular Canadian folk singer to that newer, more polished genre of internationally known singer-songwriter. His voice was also more polished; less nasal and more of a sweet baritone, capable of heartache and whimsy (“Poor Little Allison,” “Cobwebs & Dust,” the beautiful lullaby “The Pony Man”) as well as erotic tension (“Approaching Lavender,” “Baby It’s Alright,” “Your Love’s Return”). The LP started with a classic folk-style “Minstrel of the Dawn,” which pretty much laid out the sentiment of the collection: “The minstrel of the dawn is here to make you laugh and bend your ear…. All full of thoughts, all full of rhymes…. Listen to the strings, they jangle and dangle while the old guitar rings.” Strings played a huge part here, much more so than in his previous work; these were mostly arranged by Randy Newman, although “If You Could Read My Mind” was a masterful arrangement courtesy of Nick DeCaro.

Listening to the album 50 years later, it’s impossible to think that anyone could have doubted that “If You Could Read My Mind” would be a hit. I don’t get tired of hearing it. Put a headset on and admire the intricate layers; not just the obvious swooping strings, but Red Shea’s gorgeous guitar work that leads you further into the song, Rick Haynes’s solid bass, and Lightfoot’s own steady picking. Lightfoot has said in the excellent documentary named after this song that he wanted his band to sound like one person playing, and it is often hard to tell where his playing ends and Shea’s and Haynes’s begins. Sometimes listening to music from the past returns you to the past in a sweetly nostalgic way. But this doesn’t sound dated. It’s still fresh and accessible, and I can still find something new every time.

–Karen Schlosberg