Arts Reconsideration: The 1971 Project – Celebrating a Great Year in Music (October Entry)

Arts Fuse writers continue their countdown of great music celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. This month’s diverse list includes Los Tigres Del Norte, Santana, Gentle Giant, Sparks, and T-Rex.

Bang a gong for the music celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. From the gritty border realism of Los Tigres Del Norte to the fantastical sonic worlds of prog-rock’s Gentle Giant — and from the restless artistic experimentation of Santana and Sparks to the detailed compositional control of T-Rex — the music of 1971 continues to resonate, hopefully to open ears in 2021.

For those who missed them, here are the 1971 music entries for February, March, April, May, June, July, August, and September.

What are your impressions and memories of these records, and what are your favorite masterpieces from 1971? Let us know in the comments.

– Allen Michie

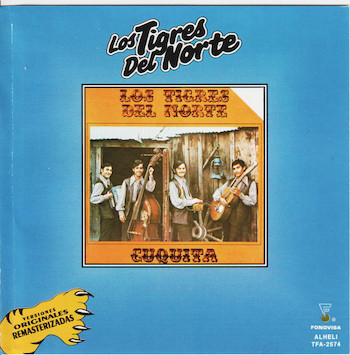

Cuquita – Los Tigres Del Norte (Golondrina)

In the late ’60s, a Mexican band composed of three brothers and a cousin from the tiny pueblo of Rosa Morada, Sinaloa, crossed the border into California, proclaiming their intentions to achieve commercial success in the US playing norteño music. The border officers, as the story goes, asked them the name of their band. The four children, in their early teens, had no answer. Though they had been playing in Los Mochis, Sinaloa, and Mexicali before deciding to move farther north, they had not yet settled on a name. The border officers, perhaps sensing the relentless drive burning inside the adolescents, offered a suggestion: “Los Tigritos,” or “The Little Tigers.” The teens adjusted it to fit the great future they imagined for themselves on the border, and Los Tigres del Norte (“The Tigers of the North”) were born.

They would become an international success, and arguably the most influential norteño band that ever existed. Yet when they recorded their second album in Los Angeles, 1971’s Cuquita, they were still tigritos. Their repertoire had until then consisted mostly of traditional rancheras, although in 1971 the group and their English record producer would encounter an LA-based mariachi band singing the song that would later bring Los Tigres del Norte explosive fame in 1974. That song, “Contrabando y traición” (“Contraband and Betrayal”), would later be pointed to as the birth of narcocorrido, or “narco ballads.” A scandal would erupt in Mexico with the inclusion of narcocorridos like “Contrabando y traición” in a schoolbook by the Ministry of Education, with conservatives blasting what was deemed a glorification of the drug trade. For their part, Los Tigres have always insisted that they tell the stories of their people, good and bad.

To Los Tigres, there is no “narcocorrido,” there is only corrido; ballads about real life. And in 1971’s Cuquita we begin to see the band come into their own as corrido performers. “Por una mujer casada” (“For a Married Woman”) speaks of treachery, while songs set in the transnational Rio Grande Valley of Texas (el valle de tejas) begin to intimate their future cross-border subject matter. “Jacinto Treviño” tells of a young Tejano man who guns down güeros (white men) in a bar fight, while “La Novia de San Benito” (“The San Benito Girlfriend”) celebrates finding love in the small Texas town. “Custodio” tells of the revenge murder of a Sonoran man while sitting down to eat, inviting his murderer to a cigarette and a Pepsi before being shot.

Other songs are more buoyant. There’s “La ranita” (“The Little Frog”), and the supremely endearing “La carretera” (“The Highway”): “Oh, what curves, and I, without brakes! The highway has the shape of a woman; if you’re not careful, you won’t be able to stop!” The song has you singing along, even if you don’t know Spanish. “I knew a chick, she was so curvaceous, I couldn’t stop, and it sent me to…” We’re left to figure out the meaning of chingada, a Mexicanism that’s close to “sent me to Hell,” though it is probably closer to “fuck.”

We’re now 50 years on, and Los Tigres have recorded over 50 albums and over 500 songs. “Los jefes de jefes” (“bosses of bosses”), as they have described themselves, keep traveling on. What Cuquita shows us is that the distinction between the corrido and the narcocorrido is nonexistent for these populist singers of truth. Or, on the other hand, it shows us the power of the introduction of the narco ingredient: it elevated four talented corrido singers from rural Sinaloa to international fame.

– Jeremy Ray Jewell

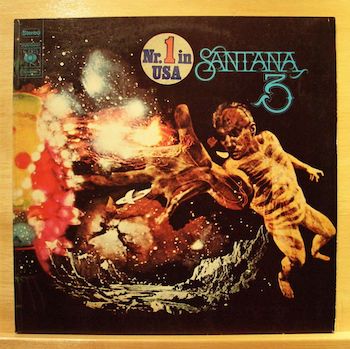

Santana III – Santana (Columbia/Legacy)

The rock outfit Santana rode waves of commercial success, none more surprising than the group’s initial fame at the dawn of the ’70s. A scorching 1969 set at Woodstock — where namesake guitar guru Carlos Santana literally tripped out onstage – sparked huge momentum for the band’s first few albums. Sophomore album Abraxas topped the charts in 1970, sealing the deal with indelible covers of Peter Green’s “Black Magic Woman” and Tito Puente’s “Oye Como Va.”

The rock outfit Santana rode waves of commercial success, none more surprising than the group’s initial fame at the dawn of the ’70s. A scorching 1969 set at Woodstock — where namesake guitar guru Carlos Santana literally tripped out onstage – sparked huge momentum for the band’s first few albums. Sophomore album Abraxas topped the charts in 1970, sealing the deal with indelible covers of Peter Green’s “Black Magic Woman” and Tito Puente’s “Oye Como Va.”

Santana could have sold out with a slicker follow-up, a direction followed to greet both the ’80s and ’00s. But, on Santana III, the guitarist’s band only doubled down on its mission of bringing fiery Latin percussion to mainstream rock with a self-produced session of deeper, darker grooves.

The 1971 album also hit No. 1, even while it cast a mysterious, slightly murky mood. The record doesn’t begin with a bang, but with a slow build of tinkling cowbells and congas into the snaky bass and wah-wah-tinged guitar of “Batuka,” which bursts into a swirling jam. It drops back to whispers until a whacked timbale cues the melodic riff of the Gregg Rolie–sung single “No One to Depend On.”

That song highlights the arrival of a teenage Neal Schon, who declined a tour with Eric Clapton’s Derek and the Dominos to join Santana as second guitarist (before later forming Journey with Rolie). He provides a trilling solo and rare-for-Santana guitar harmonies. Then Carlos generously gives Schon yet another spitfire solo in the album’s other single, “Everybody’s Everything,” a funky change-of-pace churn jabbed by the Tower of Power horns and resonant timbale fills.

Naturally, Carlos finds plenty of spots for his vibrato-wrung guitar to soar, particularly on “Toussaint L’Overture,” a hard-charging feature for the percolating percussion section that adds spirited cross-chanting, Rolie’s splashing organ ride, and David Brown’s incessant bass. The guitarist even takes a passable, yearning vocal on the accessible, acoustic-brushed “Everything’s Coming Our Way.”

Ad-hoc lead vocals pose a relative weak point, particularly Rolie’s seductive croon in “Taboo.” Yet Santana III breathes with a consistency of mood and energy, heavy with upbeat jams including “Jungle Strut” and the Puente-penned closer “Para Los Rumberos.” Percussionists Michael Carabello, Thomas “Coke” Escovedo (who joined the sessions when Jose “Chepito” Areas left with a brain aneurysm), and drummer Michael Shrieve make the group pulse like a fierce, earthy organism.

Santana’s third album was the last by the original lineup before its leader favored jazz fusion on the follow-up Caravanserai and (with guitar foil John McLaughlin) the spiritual Love Devotion Surrender. It was also the group’s last album to hit No. 1 until 1999’s cameo-studded pop outing Supernatural. If you want to return to a time when Santana truly tapped the supernatural, Santana III exudes that vibe.

(A 2006 Legacy edition adds a great second disc of a 1971 Fillmore West concert with six Santana III songs, Miles Davis’s “In a Silent Way,” and Abraxas standouts “Black Magic Woman/Gypsy Queen” and “Incident at Neshabur.” The original group also recorded 2016’s Santana IV, alas only for a short-lived reunion.)

– Paul Robicheau

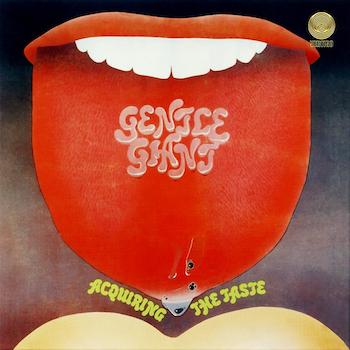

Acquiring the Taste – Gentle Giant (Vertigo)

Gentle Giant wasn’t the first of the British progressive rock bands that helped shape the musical landscape of the first half of the ’70s (though they weren’t far off); nor were they among the most successful (in this instance, they were very far off). They do, however, have the distinction of articulating a powerful credo for the movement, which appeared in the liner notes of their second album, 1971’s Acquiring the Taste:

Gentle Giant wasn’t the first of the British progressive rock bands that helped shape the musical landscape of the first half of the ’70s (though they weren’t far off); nor were they among the most successful (in this instance, they were very far off). They do, however, have the distinction of articulating a powerful credo for the movement, which appeared in the liner notes of their second album, 1971’s Acquiring the Taste:

It is our goal to expand the frontiers of contemporary popular music at the risk of being very unpopular. We have recorded each composition with the one thought — that it should be unique, adventurous and fascinating. It has taken every shred of our combined musical and technical knowledge to achieve this. From the outset we have abandoned all preconceived thoughts on blatant commercialism. Instead, we hope to give you something far more substantial and fulfilling.

It was rather a ballsy proclamation and, true to their word, the music on the album was unique, adventurous, and fascinating — it was also very unpopular. Still, that has more to do with the whims of a fickle record-buying public; the fact is, Gentle Giant are more popular in 2021 than they ever were during their 1970-1980 lifespan. High-profile CD reissues, tribute bands, and receiving the Lifetime Achievement Award from Prog Magazine in 2015 have inspired old fans to dust off their old recordings and attracted new fans to the group’s unique mix of styles, dynamics, and instruments.

That mix was perhaps never more fully realized than on Acquiring the Taste, produced by the great Tony Visconti (David Bowie). The band has always had a medieval feel, and the opening track, “Pantagruel’s Nativity” (based on the work of French writer François Rabelais), features three horns, two guitars, multiple keyboards (including the standard prog arsenal components, Moog synthesizer and Mellotron), four-part vocal harmonies, and a vibraphone solo. The solo is played by Kerry Minnear, who, like the other members of the group, is a multi-instrumentalist, specializing in keyboards, tuned percussion, and cello. His work stands out on this album, as he wrote, arranged, and performed in a percussion section on one song and a string quartet on another; in addition, the title track is a solo piece he performs on the Moog.

Unlike other prog groups, Gentle Giant was actually less about soloing than about contrapuntal compositions and intricate arrangements. Still, for those who favor shredding, guitarist Gary Green delivers the goods in “The House, The Street, The Room” and bassist Ray Shulman lets loose on electric violin on “Plain Truth.” Lead vocals are divvied among Derek Shulman, Phil Shulman, and Minnear. Gentle Giant is indeed an acquired taste — one well worth acquiring, and this is a fine place to start.

– Jason M. Rubin

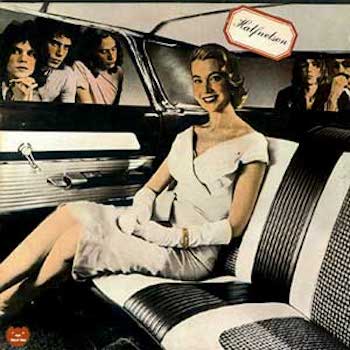

Halfnelson – Sparks (Bearsville)

Halfnelson – Sparks (Bearsville)

Before the triumph at Cannes, before the collaborations with Edgar Wright and Faith No More and Jane Weidlin, before the appearance on Saturday Night Live, before the experiments with Italodisco and New Wave, before the triumphant string of glam rock albums in the ’70s, Ron and Russell Mael of Sparks were two oddball Angeleno brothers with dreams of stardom.

Their debut album, Halfnelson (rereleased in 1972 as Sparks), found the Sparks-to-be dabbling in hard rock, Gilbert and Sullivan–inspired operetta, and post-Kinks vignettes — sometimes within the same song. While vocalist Russell Mael had yet to discover his falsetto voice, his androgyny and breathy intonation recall none other than Marlene Dietrich. Ron, his older brother, switches gracefully between barrelhouse piano and elaborate melodic motifs that evoke his classical training. The backup band deftly complements the brothers’ eclectic influences; the rhythm on opener “Wonder Girl” sounds like something out of a ’30s burlesque house, while the backing on the poignant “Slow Boat” suggests a lounge band at the Holiday Inn in Heaven. Todd Rundgren’s low-budget production has an inventive and witty quality with some nifty stereophonic touches. Though the Brothers Mael were a few years off from their breakthrough, Halfnelson sounds like the birth of many bands whose members weren’t even born in 1971.

– Chelsea Spear

Electric Warrior – T. Rex (Reprise)

Like many of the best pop albums, Electric Warrior hides its sadness along its edges. Guitar wizard and T. Rex frontman Marc Bolans churns out earworm riff after earworm riff, and they are all infused with an air of loneliness. The lyrics are part of an inner monologue that darts between biting wit and sobering reflection. Bolan is the album’s center, eccentric and isolated. The resulting listen is a world unto itself: a rock ‘n’ roll record as serene as it is raucous.

Like many of the best pop albums, Electric Warrior hides its sadness along its edges. Guitar wizard and T. Rex frontman Marc Bolans churns out earworm riff after earworm riff, and they are all infused with an air of loneliness. The lyrics are part of an inner monologue that darts between biting wit and sobering reflection. Bolan is the album’s center, eccentric and isolated. The resulting listen is a world unto itself: a rock ‘n’ roll record as serene as it is raucous.

In fact, Electric Warrior is remarkably quiet. “Mambo Sun,” the opener, slowly emerges from nothingness and takes the form of a soft, foot-tapping riff. Bolan croons over the guitars with a witty devotional passion: “Beneath the mountain range/I’m Doctor Strange/For you.” The solo that follows gently mirrors the verses, dancing over the drums. Bolan draws you in, making you listen to every note.

This light touch accentuates Bolan’s sublime talent as a riffmaker. His guitar leads float on top of hypnotic rhythms that are as smooth as they are danceable. There’s “Bang a Gong (Get it On),” the album’s smash hit; the guitar swaggers forward, muddled with syncopated notes and distortion. It all sounds deliciously raunchy, and Bolan sings with a smile and a wink, capping off the record’s most straightforward jam. “Lean Woman Blues” adopts a lurching shuffle, becoming louder with the arrival of outlandish bluesman impersonations: “When you’re the love of my life/and you gouge me with a knife/yea I’m blue.” The riff escalates as the verse builds, finally bursting into a fiery solo.

These moments of pure rock are balanced out by gentler if darker sentiments. “Cosmic Dancer” is an orchestral ballad; acoustic guitars and strings mesh as Bolan spins out a mordant fantasy. “I danced myself right out the womb/I danced myself into the tomb,” he laments. “Life’s a Gas” turns a parting of ways into an opportunity for cosmic contemplation accompanied by somber strings: “I could have loved you girl like a planet.” In these moments, Bolan is the eye of a hurricane, serene and self-involved, ruminating on the surrounding chaos.

This is what makes Electric Warrior such a deeply personal listen. Bolan’s brand of intimacy is generated out of quiet riffmaking, offhand ruminations, and his distinctive comic strangeness. Song by song, in an album of enormous depth filled with catchy hooks and penetrating meditations, he creates his own mystique.

-Alex Szeptycki

Tagged: Acquiring the Taste, Alexander Szeptycki, Allen Michie, Chelsea Spear, Cuquita, Electric Warrior, Gentle Giant, Jason M. Rubin, Jeremy Ray Jewell, Los Tigres Del Norte, Paul Robicheau, Santana, Santana III, Sparks, halfnelson