Arts Reconsideration: The 1971 Project — Celebrating a Great Year in Music (August Entry)

It would be nice to introduce the August entry in the Arts Fuse’s ongoing 1971 Project with a pithy summarizing comment that unites all the entries with a common theme, but this month’s collection includes both Bach’s Complete Cantatas and Black Sabbath’s Master of Reality. So you’re on your own! Read, listen, and revel in the imaginative and rebellious creative explosion of music celebrating its 50th anniversary this year.

Let us know in the comments your own experiences with these classics, and tell us your own favorites from 1971. If you can locate a common thread that ties together the Allman Brothers, Roy Brown, Bach, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, and Black Sabbath, you win the bragging rights. (Maybe each album has a track in the key of F major?)

For those who missed them, here are the 1971 music entries for February, March, April, May, June, and July.

— Allen Michie

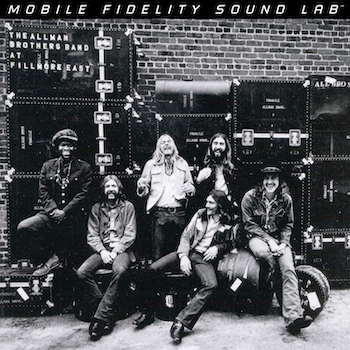

The Allman Brothers Band, At Fillmore East (Capricorn/Atlantic Records)

“Hey, listen, it’s six o’clock, y’all. Look here — we recorded all this. This is going to be our third album. And thank you for your support — you’re all on it. (We ain’t going to send you no check, but thanks for your help!)”

“Hey, listen, it’s six o’clock, y’all. Look here — we recorded all this. This is going to be our third album. And thank you for your support — you’re all on it. (We ain’t going to send you no check, but thanks for your help!)”

With those words, Gregg Allman sent some 2,000 of us squinting into the morning sun after an epic closing night of peerless blues-rooted improvisation at Bill Graham’s Fillmore East. The three-evening run originally called for the Allmans to open for bluesman Johnny Winter but, after half the opening set, the audience called it a night before Winter could play a note. The Allmans were quickly promoted to headliners — with the attendant freedom to jam as long as they wanted in their second sets.

A blues-drenched band at the peak of its powers, the Allmans represented a confluence of influences. The twinning and twining of guitar leads by Duane Allman and Dicky Betts came from Paul Butterfield’s East-West band and Quicksilver Messenger Service (with a nod to the close harmonies of the brothers Louvin and Everly). Bassist Berry Oakley drew on the melodic, virtuosic, and decidedly electric bass concepts of the School of James Jamerson and adherents like Jack Bruce, Jack Casady, and Phil Lesh. Inspired by the percussive interplay of Bill Kreutzmann and Mickey Hart in their paterfamilias, the Grateful Dead, the pairing of drummers Butch Trucks and Jaimoe (Jai Johanny Johanson) gave the band an agile and responsive underpinning. And, atop all this — along with his own organ work, rooted in Booker T. and Jimmy Smith — rode the blues- and country-inflected vocals of Gregg Allman.

By 1971, the 45 RPM single was giving way to the LP, which found a home on new album-oriented FM radio formats that welcomed a generation of rock musicians with Miles Davis and John Coltrane in their ears, ready to stretch out and bring their audiences with them. After the only moderate success of their eponymous debut LP and its successor, Idlewild South, the Allmans had finally persuaded Atlantic to give them an opportunity to flee the studio and show those who had never caught their classic configuration live what all the fuss was about. Helmed by legendary recording engineer and producer Tom Dowd — responsible for Ray Charles’s double-sided “What’d I Say” and John Coltrane’s Giant Steps album, among countless other sessions — the band was captured with a fidelity (including stereo separation that was crucial for a band with dual guitarists and drummers) that many musicians could only envy.

The eight-part documentary 1971: The Year That Music Changed Everything (more like “The Year That Everything Changed Music”) leans pretty heavily (and with questionable rationales) on the notion that 1971 was the end of an era. In the case of At Fillmore East, though, the description is warranted. Three and a half months after the March recordings, the Allmans were chosen by Bill Graham to be the final performers at the closing night of the Fillmore East. And if the shuttering of one of the best rock venues ever was a sad occasion, it was dwarfed by the tragic death of guitarist Duane Allman in a motorcycle accident on October 29. The band soldiered on, enduring the eerily similar passing of bassist Berry Oakley the following year, and eventually flourished again (with the addition of guitarists Warren Haynes and Derek Trucks) in the ’90s. But 50 years on, At Fillmore East remains justly celebrated as one of the greatest live albums ever.

— J.R. Carroll

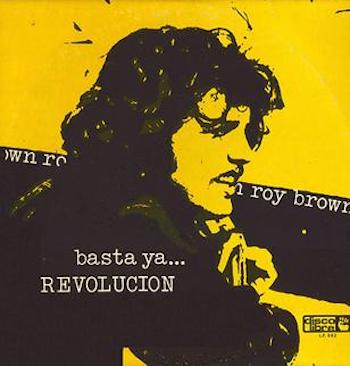

Roy Brown, Basta Ya… Revolución (Disco Libre)

Roy Brown was the Puerto Rican iteration of the familiar folk revival singer-guitarist. His first album began to draw significant attention in 1970 with demonstrations that year at the University of Puerto Rico. A 20-year-old student named Antonia Martínez was shot and killed as she screamed “Asesinos! [Murderers!]” at riot police beating her fellow students. Brown made Martínez the subject of the first song on his second album, Basta Ya… Revolución, released in 1971 by Disco Libre, a label owned by the pro-independence Puerto Rican Socialist Party. The track is called “Antonia murió de un balazo” [“Antonia Died of a Gunshot”]. It calls university chancellor Jaime Benitez a murderer and places the killing in the context of US imperialism.

Roy Brown was the Puerto Rican iteration of the familiar folk revival singer-guitarist. His first album began to draw significant attention in 1970 with demonstrations that year at the University of Puerto Rico. A 20-year-old student named Antonia Martínez was shot and killed as she screamed “Asesinos! [Murderers!]” at riot police beating her fellow students. Brown made Martínez the subject of the first song on his second album, Basta Ya… Revolución, released in 1971 by Disco Libre, a label owned by the pro-independence Puerto Rican Socialist Party. The track is called “Antonia murió de un balazo” [“Antonia Died of a Gunshot”]. It calls university chancellor Jaime Benitez a murderer and places the killing in the context of US imperialism.

Brown was echoing the sentiments of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. In the ’30s that party had steered the nationalist cause in the direction of violent revolution. This in turn led to violent repression. In 1935, in fact, nationalist protesters were killed by police in the Río Piedras area of San Juan where Martínez would be killed 35 years later. What happened in between was no less violent. In 1950 a nationalist attempted to assassinate President Truman, and in 1954 Puerto Rican nationalists opened fire inside the US Capitol. Their cause never generated much electoral traction. It never received more than 6 percent in any vote, making it considerably less popular than secession in Texas today. Still, Puerto Rican nationalism remains alive as a fringe movement with a disturbing habit of terrorism.

The Vietnam era, however, brought about a moment when the nationalist mission could have become more viable than ever before. Brown was the voice of that movement. His style borrowed from Cuban Nueva Trova, itself a variety of nueva canción, the politically motivated Latin American folk revival. Nueva trova was born of the Cuban Revolution, but it hearkened back to the 19th-century trovadores — traveling guitarists in eastern Cuba. For Brown, the connection was more than stylistic; he steered this tradition in a newer, boomer direction. For example, the track “Pa’l viejo y que adivine” champions the rebellion of youth via the vernaculars of the past.

“Lamento nuyorquino” [“New York Lament”] echoes the 1929 classic “Lamento Borincano.” Brown uses this upbeat blues, drawing on Boricuan pronunciation, to paint a collage that depicts a city inhabited by folksingers, capitalists, communists, PR street gangs, and Spiro Agnew. At one point he proclaims, “most of them say that they know that war is a business, and that the moon is a toy for the king of the shitshow.”

The rest of the album is varied. Brown argues that the centrist position on the island is based on false promises of progress, provides speculative Marxist poetry about the utopia-to-come, belts out a nationalist call-to-arms, and supplies movingly idyllic tributes to home, along with dismissively bitter references to New York. Perhaps the most moving track is “Negrito bonito,” the tale of a black migrant who escapes the sugar plantation, where work means “fighting with nothing without even knowing why.” He dreams in dialect of “New York, where everything is better,” but he ends up fighting yet another meaningless fight.

All in all, Basta Ya… Revolución boasts some fancy guitar work with fine rhythm accompaniment. But Brown’s pleasant, reverb-drenched vocals push positions that feel infinitely more dated today than anything from Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. Still, doesn’t that just prove how distinct the culture of the island really is? Interestingly, taken as the sum of its parts, the disc is far less moving (and far more didactic-feeling) than the work produced by other nueva canción greats such as Quilapayún and Violeta Parra. If anything, Brown’s relative proximity to the US makes his social commentary feel poignantly mum on the shared struggles going on at the time.

In 1974 a nationalist group set off multiple bombs in New York City, Washington, Chicago, and Puerto Rico. It didn’t earn them any sympathy on the island or abroad. As the Vietnam era turmoil waned, Brown gradually moved into songs with other subjects. He relocated to New York, leaving the Disco Libre label. Nueva Trova itself evolved into a less political direction as well. Yet the Brown influence is still there, implicit in other Puerto Rican songs, such as “Latinoamérica” by Calle 13. Perhaps only now, in the age of Daddy Yankee and Reggaeton, can the Boricua activist musician accept his/her role as an ideologically charged intermediary between the two Americas.

— Jeremy Ray Jewell

Johann Sebastian Bach, Complete Cantatas, conducted by Harnoncourt and Leonhardt (Telefunken)

1971 was a watershed year for classical music, as I clearly recall (I was 22). That was the year that the first volume of Telefunken’s LP series of the complete Bach cantatas came out. Some pieces were conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt, others (from the keyboard) by Gustav Leonhardt. The performers were all male (except in two secular cantatas written for women soloists), in order to replicate the conditions under which Bach toiled at the St. Thomas Church in Leipzig. Period instruments were used — or new ones built according to old designs — and were played in ways that treatises of the time seemed to indicate. (We know more now!) Crucially, the instruments were few in number, even though Bach repeatedly asked the town council for more players. Tempi were much brisker than in previous recordings, and once-plodding rhythms now danced and skipped.

1971 was a watershed year for classical music, as I clearly recall (I was 22). That was the year that the first volume of Telefunken’s LP series of the complete Bach cantatas came out. Some pieces were conducted by Nikolaus Harnoncourt, others (from the keyboard) by Gustav Leonhardt. The performers were all male (except in two secular cantatas written for women soloists), in order to replicate the conditions under which Bach toiled at the St. Thomas Church in Leipzig. Period instruments were used — or new ones built according to old designs — and were played in ways that treatises of the time seemed to indicate. (We know more now!) Crucially, the instruments were few in number, even though Bach repeatedly asked the town council for more players. Tempi were much brisker than in previous recordings, and once-plodding rhythms now danced and skipped.

The whole Telefunken (later Teldec) Bach cantata series proved a revelation. Dozens of these works had lain unperformed for over 200 years. We were surprised to find how varied they were, and often how grim. (Richard Taruskin would later take glee in reporting this grinding dourness in his multivolume Oxford History of Western Music.) The small, pungent performing forces made the works feel weirdly fresh, freshly weird, and, yes, lively. I remember stacks of the LP boxes on tables at the Harvard Coop (bookstore), where they were quickly snapped up. The skillful recordings that those boxes enshrined remain available 50 years later as CDs (through the lively market in unopened or used CDs), as downloads, and through streaming services such as Spotify.

— Ralph P. Locke

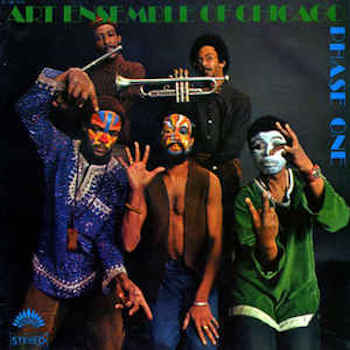

Art Ensemble of Chicago, Phase One (America)

Formed in Chicago in the mid ’60s, the venerable free jazz quartet—made up of bassist Malachi Favors, saxophonist Roscoe Mitchell, trumpeter Lester Bowie, and saxophonist Joseph Jarman—didn’t arrive at its raucously free-floating musical style until the late ’60s, after it had moved to Paris and had the good fortune to choose Don Moye as its regular drummer. Between 1969 and 1971, the group came up with its permanent name, Art Ensemble of Chicago, and made more than a dozen albums’ worth of material, released on various French and American labels.

It is achingly revelatory to listen to this music now. The band is forging its eclectic-to-the-max identity, a seriously playful fusion (and sometimes wry confusion) of ragtime and cacophony, bebop order and squawking disorder, a spontaneous sonic zigjag that intertwined guttural street sensibility and African spirituality. Like so many of the memorable albums made during this period, adventurous musicians were honing the experimentation of the ’60s, poking and probing boundaries for a receptive listenership. Way out became, at least for a while, a way of life in the arts.

The live albums Art Ensemble of Chicago released at the time, 1969’s Live in Paris and 1972’s Bap-Tizum, tend to be the favorites of critics. And it is hard to argue with that. But, for me, Phase One, recorded in 1970 (issued in 1971 on the French America Records imprint), is a very special album, perhaps because it feels as if the band is in the studio for the sake of solidifying its vision. The succinctness here is propelled by an in-yer-face confidence. The album contains two long (just over 20-minute) performances: “Ohnedaruth” is a relatively hard bop piece dedicated to John Coltrane, and “Lebert Aaly” is an amusingly atmospheric homage to Albert Ayler.

“Ohnedaruth” starts off with a trademark Moye percussion solo in which he embraces the role of godling, creating and organizing the sounds that are going to make up the stars and planets. The stream of vibrations — tweaks, swirls, and chinks — dance nimbly by. This intro leads to a succession of powerful saxophone solos that rip and race along, moving from the accelerated to the melancholic, disciplined riffs jumping (unpredictably) into over-the-top growls. “Lebert Aaly“ contains flickers of Ayler’s trademark wails, but this is really a joyous meditation on the blare of urban life. At one point, we seem to be listening to a herd of trumpeting elephants as they roll around in a bed of rusty tin cans. In this memorable album, an apex of the group’s halcyon time in Paris, the Art Ensemble of Chicago discovered it could best reinvigorate the giants by twisting itself in any direction it wished.

— Bill Marx

Black Sabbath, Master of Reality (Warner Bros)

The surprise success of Black Sabbath’s eponymous debut album in 1970 was eclipsed only by the surprise mega-success of their follow-up later the same year, the iconic Paranoid. If Sabbath had stopped then and there, they would still be considered one of the High Priests of Heavy Metal. But they didn’t. With 1971’s Master of Reality, the band effectively flipped the bird at the carping critics — what do they know? — and cemented their legacy.

The surprise success of Black Sabbath’s eponymous debut album in 1970 was eclipsed only by the surprise mega-success of their follow-up later the same year, the iconic Paranoid. If Sabbath had stopped then and there, they would still be considered one of the High Priests of Heavy Metal. But they didn’t. With 1971’s Master of Reality, the band effectively flipped the bird at the carping critics — what do they know? — and cemented their legacy.

Cocky and coke-riddled, Black Sabbath entered the studio in February 1971 with the intention of doubling down on their doomy lyrics and leaden sound. They unapologetically coalesced their fan base of wasted, disaffected teens with anthems such as “Sweet Leaf” — an ode to marijuana with the suitably stupid line, “I love you sweet leaf, though you can’t hear” — and “Children of the Grave,” an antiwar song for non-pacifists (“Revolution in their minds, the children start to march/Against the world in which they have to live and all the hate that’s in their hearts/They’re tired of being pushed around and told just what to do/They’ll fight the world until they’ve won and love comes flowing through”).

Sabbath’s genius, spotlit on Master of Reality, was the complete saturation of a decidedly downer tone throughout their lyrics, melody, rhythm, and performance. Bill Ward’s heavy drumming, Geezer Butler’s thick-as-tar bass and pessimistic words, Tony Iommi’s brilliantly dark guitar riffs, and Ozzy Osbourne’s lunatic caterwauling created a hellish atmosphere that made their albums a listening experience like no other. Led Zeppelin would explore Middle Earth and Valhalla, yet inevitably the band came back to the boudoir. Same with Deep Purple. Black Sabbath has precious little interest in hedonism, as the album’s closer “Into the Void” makes clear:

Rocket engines burning fuel so fast/Up into the night sky they blast

Through the universe the engines whine/Could it be the end of man and time?

Back on earth the flame of life burns low/Everywhere is misery and woe

Pollution kills the air, the land and sea/Man prepares to meet his destiny

To their credit, Black Sabbath offered a couple of left turns on Master of Reality. For one, they finally wrote a true love song, the sensitive ballad “Solitude.” A song about heartbreak (of course), it nevertheless finds them in new territory, with singer-songwriter lyrics such as, “You just left when I begged you to stay/I’ve not stopped crying since you went away.” Iommi even plays flute and acoustic piano on the track.

Also, there are two solo instrumentals by Iommi. The first, “Embryo,” is a half-minute classical-style intro to “Children of the Grave.” The other, “Orchid,” is only a minute longer but it’s a more substantial composition, featuring some nimble acoustic guitar playing that shows Iommi had skills beyond being a heavy metal riffmaster. Such experiments in form set the stage for continued growth on their next few albums.

— Jason M. Rubin

Tagged: Allen Michie, Art Ensemble of Chicago, asta Ya… Revolución, At Fillmore East, Bach, Bill-Marx, Black Sabbath, Complete Cantatas, J.R. Carroll, Jason M. Rubin, Jeremy Ray Jewell, Masters of Reality, Phase One, Ralph Locke, Roy Brown