Arts Remembrance: Why Jazz Needed Richie Cole

By Allen Michie

The master alto saxophonist Richie Cole died on May 2 at age 72. The cause of death has not been announced, so it’s unknown for now if it was related to COVID-19.

The late Richie Cole. Photo: Aaron Jackendoff Photography

2020 has been a horrible year for losing jazz musicians. It’s only April, but so far the grim toll already includes Manu Dibangu, Andy González, Henry Grimes, Jimmy Heath, Lee Konitz, Mike Longo, Jymie Merritt, Ellis Marsalis, Bucky Pizzarelli, Claudio Roditi, Wallace Roney, McCoy Tyner, and Hal Wilner. The jazz world has hardly even had time to recover from the unexpected loss of trumpeter Roy Hargrove in 2018 before all of this started happening. Here’s hoping someone is keeping Sonny Rollins and Wayne Shorter, both already with respiratory problems, locked in enormous Ziploc bags somewhere a mile underground.

But there’s something particularly sad about the passing of Richie Cole. What you just read may be the only place where the words “sad” and “Richie Cole” are in the same sentence. Cole was unerringly cheerful, both in his music and (so I am told by many) in person. This is not because he lived a life free of tragedies. He lost two wives, witnessed the murder of his best friend and musical partner Eddie Jefferson, struggled with alcoholism, and had the dedicated jazz musician’s usual struggles of squeezing a living wage out of the record companies and the road. He could probably play the blues, because his mind was a thesaurus of jazz licks and patterns, and his fingers moved at the speed of thought. But he didn’t.

Cole knew himself, his instrument, his sound, and his chosen genre well enough to line them up seamlessly. You could tell it was him in three notes. His tone was fluid, bright, and clear, in a direct line from Johnny Hodges to Cannonball Adderley to his mentor Phil Woods. He may not have been widely influential, like David Sanborn or Michael Brecker in his own generation, but there was a singular Richie Cole style of music, and no one could play it better. He was grateful for what he learned from his elders and peers, and he was generous with what he passed on to his students and colleagues. What more can you ask of a jazz musician?

The signature Cole style was uptempo melodic bebop with an unapologetic commercial appeal. His records — some 50-plus albums, including who knows how many bootlegs and foreign releases — are usually slickly produced, recorded bright and tight with jangly pianos and punchy drums. It’s all about that treble, ’bout that treble, no bass. If the tune was supposed to swing, it was going to swing HARD, with rim shots and walking bass and rhythm guitar. Lots of poppin’ fingers got sore at Richie Cole concerts.

This is exactly what jazz needed, especially in the 1980s when Cole was hungry and in his prime. Jazz can be a forbidding and intimidating music, as can classical or opera or progressive rock. But each era of each genre has always had its popularizers, people who are usually not taken seriously by the experts but who nevertheless bring thousands of more casual listeners around to the cause. Along the way, they do a whole lot of genuine entertaining (and often sell way more records). For every Dizzy Gillespie or Miles Davis, there’s also a Doc Severinsen or Chris Botti.

The second most forbidding style of jazz, after free jazz (which Cole completely ignored except for part of one track, “Call of the Wild,” on his record Alto Annie’s Theme), is straight-up bebop. Not so-called “hard bop,” which smoothed out aspects of bebop’s harmonic language and wedded it to more accessible mainstream jazz or soul rhythms, but the most challenging kind of bebop practiced in the 1940s by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. It was angular, jagged, virtuosic, you couldn’t really dance to it, and it was devilishly difficult to play. What Cole did is take the bebop songbook, farmed it for its catchiest phrases and patterns, and reproduced them for ’80s listeners with good stereo systems spinning Steely Dan and Chuck Mangione records. But this was not bebop lite, and this was definitely not Quiet Storm, Smooth, or Adult Contemporary instrumental R&B. This is barnstorming, flag-waving, in-your-face, straight-up jazz. It was Charlie Parker for people almost, but not quite, ready for the real Charlie Parker. When Wynton Marsalis and the Young Lions arrived in the mid-’80s claiming the restoration of real-deal bebop from the kind of lackluster jazz-rock fusion players on CTI records in the late ’70s, they found an audience ready for their brand of instrumental mastery and harmonic sophistication. Many of these listeners, I would wager, had long been whistling their memorized Richie Cole solos.

The second most forbidding style of jazz, after free jazz (which Cole completely ignored except for part of one track, “Call of the Wild,” on his record Alto Annie’s Theme), is straight-up bebop. Not so-called “hard bop,” which smoothed out aspects of bebop’s harmonic language and wedded it to more accessible mainstream jazz or soul rhythms, but the most challenging kind of bebop practiced in the 1940s by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. It was angular, jagged, virtuosic, you couldn’t really dance to it, and it was devilishly difficult to play. What Cole did is take the bebop songbook, farmed it for its catchiest phrases and patterns, and reproduced them for ’80s listeners with good stereo systems spinning Steely Dan and Chuck Mangione records. But this was not bebop lite, and this was definitely not Quiet Storm, Smooth, or Adult Contemporary instrumental R&B. This is barnstorming, flag-waving, in-your-face, straight-up jazz. It was Charlie Parker for people almost, but not quite, ready for the real Charlie Parker. When Wynton Marsalis and the Young Lions arrived in the mid-’80s claiming the restoration of real-deal bebop from the kind of lackluster jazz-rock fusion players on CTI records in the late ’70s, they found an audience ready for their brand of instrumental mastery and harmonic sophistication. Many of these listeners, I would wager, had long been whistling their memorized Richie Cole solos.

What Cole did better than anyone since Sonny Rollins is tell a story in his solos. He didn’t just use structure, he used narrative structure. For starters, if his song has familiar lyrics, he’ll stick close to the opening melody and phrase it much like the human voice would pronounce the words. When it’s time for the solo, it will start with something catchy and clever. Then it’s going to build and, as it goes, it’s going to have some digressions and asides with quotes from other songs or nursery rhymes you might know to add some humor. There will be some classic bebop licks to reassure you that we’re all part of the same family with a shared frame of reference. There may be some sound effects or something flashy, like a split-second run from the very bottom of the sax up to a squealing overtone. As it comes near time for the climax, he’ll start low or slow and work up to high and fast, the rhythm section will somehow find an even harder way to swing, and he’ll often end it quickly with a phrase that luxuriates in the purity of his tone. Then, my favorite, he’ll often start the next person’s solo for them by kicking them a clever little unresolved phrase so you’ll still think about him when he’s gone.

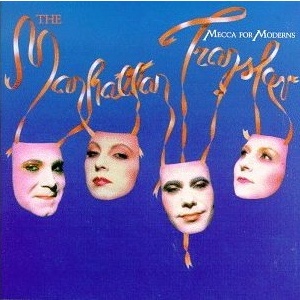

One among many, many examples would be his solo on “Confirmation” from the Manhattan Transfer album Mecca for Moderns. Cole has the unenviable task of following a scat solo from Jon Hendricks, but he starts off with a human-sounding “Whoa!” as a kind of transition at 1:23. From there it’s all about the sounds that only an alto saxophone can make. Cole plays like he only has two minutes left in his life to tell the world what they need to know about Charlie Parker, Cannonball Adderley, Phil Woods, and Richie Cole; all while he is preserving the groove and feel of the Transfer’s gig. It’s a tight little story of wit and imagination, weaving its way through the chord changes without ever losing the carefully balanced ups and downs of his narrative lines. Cole hardly stops to take a breath.

Another relatively looser example is “I Love Lucy,” the theme from the TV show, on the 1980 album Hollywood Madness. Cole has two of his best simpatico bandmates, Bruce Forman on guitar and Dick Hindman on piano. Cole, God bless him, believed that most any tune could be translated into swinging bebop (one album has the theme to Star Trek). Here he shows how bebop phrasing works over a hurtling samba rhythm. No doubt there were overdubs and multiple takes on a recording this slick; the solo was likely as much memorized as improvised. But the final product sounds effortless. It’s all here — the tension-building narrative structure, the bebop brain-twisters, the samba clichés to get your tequila party started, and the simple fun of realizing what a great song this familiar piece has been all along. The second sax solo at 4:23, after the final statement of the melody, is vintage Cole. It has triplets that bring to mind the ditzy comedy of Lucille Ball, and at 4:40 he channels the smarmy sound of Ricky Ricardo singing Cuban lounge music in his puffy sleeves with a simple, perfectly timed change in the style of vibrato. A blizzard of Parker bebop sets up a bubbling section that spins a simple salsa figure around the dance floor, then the whole thing ends with a quote from Sonny Rollins’s “St. Thomas.”

It’s not A Love Supreme, but it isn’t trying to be. Maybe an all-day playlist of Richie Cole records would get a bit predictable. But it’s fun! Jazz needed it in the ’80s and it survived the buttoned-down ’90s, finding new relevance in the jazz education programs of the 2000s as Cole forged a lucrative second career writing jazz vocal charts and ensemble arrangements. These aren’t the kind of solos that change jazz history, but they are the kind that win prizes in competitions.

You might think that a musician with such a conservative style would play it safe with other musicians. However, much (MUCH) to his credit, Cole pushed himself and stood toe-to-toe with his idols. He came from the old school of jazz saxophone that looked at jam sessions as a kind of bleeding-gums contact sport. The master matador of this unforgiving jazz subculture was the alto and tenor saxophonist Sonny Stitt. (The only saxophone player to equal Stitt on the bandstand — no one ever truly defeated him — was Sonny Rollins, and it took 14 minutes in one of the most spectacular jazz performances ever recorded: “The Eternal Triangle.” I’d bet you anything Cole could play it all note for note.) Cole, knowingly and of his own free will, recorded an entire album of duets with Stitt on alto. And, as if that wasn’t enough, Cole took on his teacher and mentor Phil Woods for an entire album, even calling the notoriously difficult bebop tune “Donna Lee” at a triple-fast tempo. And in case you thought the cheerful Cole would chicken out next to a more fearless, tormented, blues-based, experimental, and visionary alto saxophonist, Cole recorded an album of duets with Art Pepper.

Still think Richie Cole is a lightweight? Are YOU ready to record duet records with Sonny Stitt, Phil Woods, and Art Pepper? (I haven’t even mentioned that Cole was the chairman for the National Endowment for the Arts for a year.)

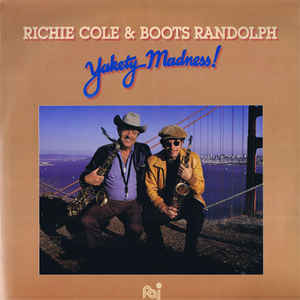

My favorite Richie Cole duet album, however — and stay with me now — is with Boots Randolph. On Yakety Madness, Cole and Randolph have a grand time. Cole pulls a performance out of Randolph like he never played before or since. Listen to “Yakety Sax,” which Richie Cole was put on this earth to play: they tell dumb jokes and laugh through their horns, they imitate any number of barnyard animals, they go streaking past the gas station, they watch reruns of Benny Hill, they drink straight moonshine, and they speculate on what it might have sounded like if Charlie Parker had done a guest spot on Hee-Haw. Yes, 2008 saw alto saxophonist Rudresh Mahanthappa’s modern classic album Kinsmen. But it also saw Yakety Madness. You’ll like both of them. But your kids and your grandparents will love one of them — guess which one.

Finally, a personal note. When I was in high school and trying to learn to play alto sax, the fantasy was to become a famous jazz soloist. But that was hardly the immediate goal. I had heard Parker, Adderley, and Woods, but I looked at them in the bewildered way a busted pine cone might look at a towering fully lit Christmas tree. First on my agenda was to survive in the saxophone section of the school big band, and maybe one day fake my way up to First Chair Alto. Maybe if I’d been hipper and more informed when I was 15, I would have checked out Johnny Hodges with the Duke Ellington band, or Marshal Royal with the Count Basie band. But instead I was hearing the Manhattan Transfer on the radio, and Richie Cole became my model.

If I could have had a one-hour lesson with him, I wouldn’t have asked him about structuring a solo, building a flexible tone that’s always in tune, or about finding a distinctive personal style. I would have asked him about his articulation. Cole’s articulation is amazing, and all saxophone players should listen for it even if Cole’s music isn’t their bag. Leading a sax section, like Cole did for the Buddy Rich band for two years, depends heavily on phrasing and swing. Both are determined largely by the subtlest ways the tongue touches the reed. Underdo it, and it’s all a slurry mess. Overdo it, and you sound old fashioned like Joe Thomas playing with Jelly Roll Morton. Get it just right, as Cole did literally 100 percent of the time, and your sound becomes as personal as a signature. Has anyone had cleaner and more musical articulation on alto sax since Parker himself?

As a jaded adult now, Cole’s music may sound maybe a bit too clean, naïve, and yes, even a bit too white, for our culturally complicated and interconnected times. But when I was a kid, Cole taught me how and why to love jazz. He taught me that it was demanding as hell, but also fun, and the better you could play the more fun you could have. This was candy-flavored medicine, and I needed it then, and maybe we could all still use some now.

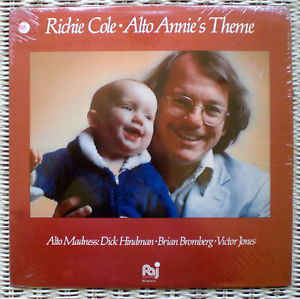

(P.S. If you’re ever bin-diving at the record store and come across Alto Annie’s Theme, the album with Cole’s adorable baby daughter Annie on the cover, grab it and guard it jealously. It’s never been released on CD, it isn’t on the streaming services, and it’s not even a passenger on the pirate ship YouTube. It has perhaps the quintessential Cole solo on one of the hardest swinging tunes in the jazz canon, “Jeannine.” Brian Bromberg plays his butt off on the bass. “Boplicity” is the sound of pure happiness in a unison solo with Cole’s favorite pianist Dick Hindman. There’s also an achingly beautiful salute to Aaron Copland. Hey Mr. Producer Man, if you’re out there reading this, the time is now for a remastered reissue!)

Allen Michie works for the state of Texas in higher education administration. He has a PhD in English from Emory University and is the author of several scholarly works. He writes articles to work out personal issues such as why he feels compelled to collect Bert Kaempfert 45s.

Thank you for this excellent tribute to Mr. Cole. If I might put an extra word on what he accomplished with Eddie Jefferson- E.J. was The Guy before Jon Hendricks came along-a true pioneer of vocalese and not getting his due. Happily, he and R.C. found something in each other’s music and in each other that lit a fire under both of them. They showed a new generation of people that singing could be real jazz and that bop improvisation could fit like a glove with singing. They will both be missed.

I very much enjoyed your tribute, but surprised there was no mention of his sublime forays with Eddie Jefferson. One of the best live performances I ever got to see was catching Richie and Eddie playing at a Holiday Inn lounge in Denver.

I’d never heard of the man before, and this was a wonderful intro– informative, breezy, passionate, and nuanced. Bravo, sir!

“I tell everyone, ‘I don’t play the saxophone; I sing the saxophone.’ I blow the saxophone as a vocalist. I tell a story. ‘I Left My Heart in San Francisco’ does not have a trumpet solo, a piano solo and a bass solo. It would ruin the whole thing. It’s a story—a short story. You want a novel? Listen to John Coltrane! And that’s good too, man!”

-Richie Cole

https://jazztimes.com/features/profiles/richie-cole-bebopper-burgh/

Note: Richie passed away peacefully in his sleep from a heart attack. Nothing to do with Covid-19.

Thank you Allen Michie for this tribute to Richie Cole. Very much on the money. I spent a lot of time with Richie when he lived in Pittsburgh, and he told me many stories over the time period when I produced and played on three of his CDs. He told me about his CD with Boots and how they enjoyed each other. He thought that although he might be sticking his neck out doing this recording because of the difference in styles, he knew it would work and it was well received. He loved staying with Boots on his ranch with Boot’s wonderful wife and son Randy, who Richie said gave him a run for his money. Richie was given the key to the city in Paducah, Kentucky, Boot’s home town. He often spoke of that experience and what a terrific player he thought Boots was. Thought I would share one of the many stories told to me spending time with Richie.

Thank you Mr. Michie.

So nice to read something by someone who ‘got’ Richie.

I especially liked that you mentioned his fearlessness. He adored Buddy Rich and would staunchly defend him whenever someone would berate him for being hard to work for. Richie could take it.

Just like to make a quick mention of his work with Bobby ‘ The Wildman’ Enriquez and Bruce Forman. – Breathtaking!

As mentioned in a previous comment Richies’ death was not Covid related. -Little comfort to those of us who knew him. He is missed.

I miss my friend every day. Richie taught me what not to play. We are kindred spirits.