Music Commentary: Nanci Griffith vs. the “New Yorker”

By Daniel Gewertz

It was the sniping tone that made the article perplexing. I would almost call it perverse. Why treat so cavalierly — even shabbily — a deceased, highly esteemed, Grammy-winning artist?

Nanci Griffith — the New Yorker feature would have driven her crazy. Photo: Wiki Common

The New Yorker finally decided to do a feature piece on the award-winning folk/country singer Nanci Griffith. It’s a good thing Griffith, who died in 2021, isn’t around to see it. It would have driven her crazy. The story, published this fall, contained a surprising share of factual errors and musical misunderstandings. But it was the sniping tone that made the article so perplexing. I would almost call it perverse. Why treat so cavalierly — even shabbily — a deceased, highly esteemed, Grammy-winning artist? It’s not as if the piece were puncturing the reputation of some overblown cultural big shot. Though a beloved star with roots music fans in cities as far-flung as Boston, Austin, Dublin, and London, Griffith and her career are no doubt unknown to most New Yorker readers.

The article was written not by a novice journalist, as I first assumed, but by Rachel Syme, 39, a New Yorker staff writer for 11 years, who normally covers — in the magazine’s own words — style, Hollywood, and culture, the latter presumably meaning the ups and downs of changing fads and fashions. Her only connection to Griffith? Growing up in the South, Syme was forced to listen to cassettes of Griffith’s songs on long automobile drives with her mother. For most of its length, the article is apparently her revenge.

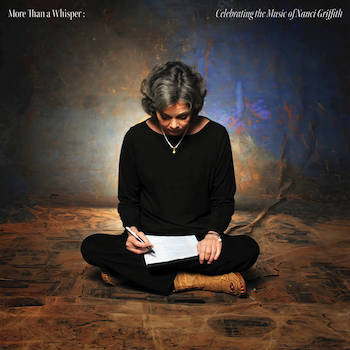

Though the album release of More Than a Whisper: Celebrating the Music of Nanci Griffith is the ostensible reason the article was written, Syme chooses not to comment on the 14 interpretations of Griffith songs. Instead, she seems to offer up a slur to counter each complimentary quote supplied by her musician sources, Jim Rooney, 85, and Sarah Jarosz, 32. Both adored Griffith’s work. Searching for pathos, the feature focuses on Griffith’s neurotic side along with her 25-year-old battle with the Texas music press. It rekindles an old trope about how country fans may have been put off by Griffith’s so-called pretentious habit of holding volumes of her favorite novels on album covers. It wonders why she never became a big country star without analyzing the aesthetic facts of the matter: Griffith’s music, and her voice, simply didn’t hit the commercial bull’s eye of the era’s country radio tastes. Yet her career is far from a failure.

Seemingly basing her analysis on those automobile rides of her childhood, Syme states that Griffith “seemed to have a special hold on a certain kind of suburban Boomer mom in the nineteen-eighties and nineties who took solace in Griffith’s high-femme cooing about loneliness, long drives, and lost love.” And if that isn’t dismissive enough, she calls one of the most admired folk/country songwriters of the ’80s and early ’90s the creator of “romantic ditties.” To be didactic for a moment, the word ditty is a belittling term defined as “a short and especially simple song.” Now, here is an honored songwriter, whose subjects included war, racism, the Dust Bowl, farming, capital punishment, and miscegenation laws, in addition to many distinctive, heart piercing songs about love, loss, and loneliness. And yet, the key term to describe her work is ditties! The New Yorker story actually echoed the word ditties in its freaking subtitle.

If Syme had mentioned her long ago musings as a child and then quickly moved on to an adult understanding of Griffith’s output, I would have read on with full appreciation. But for over half of the piece childhood griping is uppermost. Here’s another doozy: Griffith’s voice was “coquettishly girlish, aggressively dulcet, almost lamblike in its high, warbly register.” What does this even mean? Lambs bleat, right? And the warbling? It is purposeful, affecting quavering. I guess it is an acquired taste, but the trills of Griffith’s voice are an essential part of her overall power. At its best, Griffith’s vocals create a juxtaposition of honest frailty and steely strength — a merging of hope and fear, neither quality canceling the other.

If Syme had mentioned her long ago musings as a child and then quickly moved on to an adult understanding of Griffith’s output, I would have read on with full appreciation. But for over half of the piece childhood griping is uppermost. Here’s another doozy: Griffith’s voice was “coquettishly girlish, aggressively dulcet, almost lamblike in its high, warbly register.” What does this even mean? Lambs bleat, right? And the warbling? It is purposeful, affecting quavering. I guess it is an acquired taste, but the trills of Griffith’s voice are an essential part of her overall power. At its best, Griffith’s vocals create a juxtaposition of honest frailty and steely strength — a merging of hope and fear, neither quality canceling the other.

Nowhere in the article does it mention Griffith’s other voice — the rugged, muscular voice she used on certain upbeat songs. Griffith knew, at some molecular level of her artistry, that we all own different selves. Griffith separated them, her willful barroom brag seemingly unrelated to her wistful balladry. The shifting vocal approach was unusual, but not the work of a poseur: it was simply the aural emanation of her emotional complexity, the outward aspect of her writer’s imagination.

Mid-article, a pileup of factual errors made my head hurt. Syme attempts a classic New Yorker approach here, an allusive style that, to work well, depends upon firm knowledge. The best New Yorker writers sidle up to their subject to arrive at fresh, associative theories. Syme’s problem here is that she’s partly faking it. For example: she theorizes that dainty Griffith bears an artistic similarity to rock goddess Stevie Nicks, and might have found more luck if she had gone pop. This is patently insane. The vast majority of Griffith’s 34-year output sits solidly inside the traditions of country and contemporary folk. More to the point, nothing in late ’80s pop sounded even vaguely like Griffith. To push the misunderstanding further, Syme’s example of a country star who neatly transformed into a queen of pop was Linda Ronstadt! If you were a music fan alive in the final three decades of the 20th century you’d know that Ronstadt didn’t start off in country and mutate to pop. She began on the California rock scene and then diverted expertly toward a half-dozen genres, including country.

Then Syme instructs her readers about trends in country music history, and gets several correct, and a few mind-bogglingly wrong. In an attempt to explicate why Griffith didn’t become a star, she claims that moving to Nashville at exactly the time she did, 1987, may have been her unlucky undoing. She states that the era of “Urban Cowboy” music was exemplified by Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard, and by the late ’80s that era was over. In reality, the trend known as “Urban Cowboy” started with the 1980 smash-hit John Travolta movie of the same name, and its massively popular soundtrack. Purists thought the “Urban Cowboy” sound was popified and cheesy — a lesser breed of country. It was led by the likes of Kenny Rogers, Mickey Gilley, Crystal Gayle, Johnny Lee — not distinctive talents, but hardly ogres, either. Merle Haggard and Willie Nelson, meanwhile, still reside at the top of the historic heap of country legends, and did not see their popularity plummet in the ’80s. The brief era in late ’80s Nashville that Griffith was part of was labeled by the country radio industry the time of “the new traditionalists.” It fit Griffith as comfortably as any Nashville sound could have. Populated by the likes of Lyle Lovett, Steve Earle, Kathy Mattea, and Suzy Bogguss, it was the momentary attempt at higher artful ground that Earle caustically dubbed “Nashville’s Great Credibility Scare.”

Writer Rachel Syme — for most of its length, her article on Nanci Griffith comes off as an act of revenge.

Syme perceptively points out that Griffith may have been too tenderhearted for the music’s new fan base. I can buy this. She also characterizes this short trend as a more gritty sound, and claimed that Griffith wasn’t gritty enough to click with it. But the era was really about a leaner, more traditional approach: more acoustic instruments (banjo, fiddle) and smarter, fresher, more poetic lyrics. Griffith’s inability to become a big star had little to do with a lack of grit: she just didn’t fit the feminine prototype of either the old Nashville establishment or the new. She was an attractive 35-year-old woman who lacked mainstream sex-appeal. Her modest taste in period dresses and her lack of overt vocal sensuality diminished her salability. That’s the whole megillah. While Northern folk fans saw a spirited, insightful, complex sweetheart of a woman graced with searching, poetic lyrics, some Southern country fans just saw a scrawny, librarian type not worthy of a fan’s adoration.

I have read, over the years, several accounts of how Griffith’s penchant for posing on album cover photos clutching her favorite novels is akin to an arty teenager’s prideful pretension. I heard it from Nanci-haters years ago, and I chalked it up as macho posturing. There’s something about Griffith’s image that not only says vulnerable, but also unavailable. This book-clutching tendency was long-running; it included Moving On and Lonesome Dove by fellow Texan Larry McMurtry and Other Voices, Other Rooms by Truman Capote. She gave her Grammy-winning album Capote’s title, and a later Griffith CD adopted the title of a novel by Carson McCullers, Clock Without Hands. (Coincidentally, both novel and album were late career works, and minor ones.) I think the intention was multifold: to pose with a lucky keepsake, to reveal herself openly as a bookworm, and to promote her favorite writers, all of them fellow Southerners by birth, who later wandered northward. On the cover of Last of the True Believers (1986) various friends (including a very young Lyle Lovett) pose as some of the characters in her songs, while she, center stage, clutches a novel and looks like a 16-year-old innocent. (On the video of the title-track of that album look for a young Lovett singing backup.)

A favorite book was her lucky charm, a talisman meant to speed the album toward favorable fortune. But, in a mean-spirited fashion, some Texan critics derided her as a poseur, pretentiously bragging about how smart she was. During the period that Griffith was attached to MCA, a major Nashville label, there was nary a book in sight on her album covers. They may not have always known how to package Griffith, but one thing they were certain of: bookish just ain’t country.

The more I consider the poses, though, the more I see something deeper and darker. It is not just that Griffith believed writers such as Capote and McCullers were her inspirations. It isn’t coincidental that these authors were fellow Southerners who, for healthy spells, strayed far from their birthplace. By placing their works in her hands, and sometimes next to her heart, she might have been revealing that her muse arrived as much from reading as from “real life.” She may have trusted literature more than her own personal autobiography. A heart might wither, but a sturdy tale lasts.

Griffith’s supposedly unlucky move to Tennessee was concurrent with her garnering a record contract from MCA, a huge label — just as some of her creative comrades were also winning record deals. (Her former backup singer, Lyle Lovett, was one of them.) But she did enjoy moderate success in Nashville: her MCA albums — the ones geared toward a country approach — made the Top 30 country chart, and two singles reached Top 40. There was no better time for her to try to grab the brass ring. One could make the argument that nothing befits a recording artist more than being a success, but not a gargantuan one. Music made Griffith rich. She often played to concert crowds of a thousand. She was nearly always allowed to make the music she desired. If Griffith felt slighted by the Nashville establishment, she also must have known that the best American music is rarely the most popular.

Nanci Griffith at the BBC Radio 2 Folk Awards in 2010. Photo: Wiki Common

Syme also dredges up a feud Griffith had with Texan journalists some quarter-century old, when she put herself in the company of Katherine Ann Porter and other prose writers, who “had the wisdom to get the hell out” of Texas, a place that “actually eats its young” she wrote. It’s one of Syme’s best paragraphs. But it is placed directly after a statement about how Griffith didn’t chart with “Love at the Five & Dime” while her friend Kathy Mattea zoomed up the country charts to #3 with her version of Griffith’s song. The placement of these facts suggests a false connection between Griffith’s “prickly” rapport with the press and her less-than-stellar record sales. In fact, the disproportionate record sales can be attributed to small label vs. big. Griffith’s version of “Five & Dime” was released before she was on MCA, during her artistically fruitful stay at Philo/Rounder Records, and small, independent labels — even one as well known as Rounder — didn’t have the industry pull to achieve hit singles. Oddly, in Syme’s whole discussion of Griffith’s ’80s prime, Philo or Rounder isn’t mentioned. (I suspect this is because they are also missing from Griffith’s Wikipedia page.) Griffith’s first four albums have just been rereleased as a box-set under the title Working In Corners.

For the last quarter of Syme’s piece, the writer abruptly warms her approach, changing her tone toward the fond and appreciative. She adamantly rejects the charge made by Texan journalists, decades ago, that Griffith is a phony, a “faux naïf.” She grows quite eloquent in her praise. She gives old Nanci her props. But the ride to get there seems irrelevant to me, more trick than treat.

I can’t help thinking about how hurt Griffith would be if she had read the piece. Considering that most of her favorite Southern writers published in the New Yorker — even in some cases thinking of the magazine as their literary home — the article would have felt like a sneak attack. Its eventual tone of acceptance and admiration would have salved the wound to a degree. But an important message is conveyed by the astonishing age range of the artists singing on More Than a Whisper — and even the 50-year age difference between the two musicians quoted in the article: here was an artist who had a prime rich enough to affect multiple generations of admirers. The people who didn’t cotton to the voice and persona of Nanci Griffith may well have heard the sound of sadness and girlish pretension. Yet her many avid fans knew a delicate yet open heart, one that knew, in song, how to break as well as mend.

Daniel Gewertz has been influenced by the people he has interviewed for newspapers and radio, including jazz artists Ray Charles, Sonny Rollins, Artie Shaw, Dizzy Gillespie, Jay McShann, Gil Evans, Dave Brubeck, Keith Jarrett, Steve Swallow, J.J. Johnson and Milt Jackson; roots musicians B.B. King, Bill Monroe, Brownie McGhee, Vassar Clements, Phil Everly, Roger Miller, Carl Perkins and Bo Diddley; folkies Libba Cotton, Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, Leonard Cohen, Rambling Jack Elliot, Judy Collins, Roger McGuinn, Steve Goodman and John Prine; classic popsters Tony Bennett, Mel Torme, Eartha Kitt and Pearl Bailey; and film/theater artists Louie Malle, Edward Albee, Jeremy Irons, Glenn Close, Susan Anspach, Yul Brynner, Michael Douglas, Diahann Carroll, Jewel, Jack Klugman, and John Sayles. Daniel’s first live interview, at age 16, was with Art Garfunkel in 1966.

Tagged: Country Music, Lyle Lovett, Nancy Griffith, Nashville, Rachel Syme

Thanks for publishing this commentary. I also read the New Yorker article and felt exactly the same way. The “sniping tone” combined with “the factual errors and musical misunderstandings” made for an unpleasant portrait of the brilliant singer/songwriter Nanci Griffith. Publishing a lackluster hit piece like this is a cheap shot and not worthy of being published by the New Yorker. I truly wish that someone as knowledgeable as Daniel Gewertz could have written the New Yorker profile instead.

Thank you, Stephen. You know, it is possible for someone who knows little about music to write a legitimate story if they are honest, forthcoming about their perspective, and do research. This piece was the opposite of that more humble and careful approach. I guess she thought it was a dramatic way to go.

Thanks to Daniel Gewertz for this excellent piece. For whatever reason the New Yorker‘s occasional music coverage does not seem to be subject to the magazine’s famous fact-checking. A few years ago editor David Remnick wrote a heralded profile of Aretha Franklin that repeated a dubious Wikipedia claim that “Chain of Fools” ripped off an obscure gospel recored released the same year. (In reality it is far more likely that the gospel record simply offered a spiritual version of a hit of the day, which was a common practice.)

Some of the harsher criticisms that Griffith endured at the height of her popularity were surely based in sexism. Darlings like Prine and Lovett wrote more than their share of silly, playful songs without being skewered for them. But as Gewertz points out, Griffith also had reams of positive press, Grammys, and sold out audiences. That she died thinking she was unappreciated says little about her career, but a lot about how depression can be so disconnected from reality.

Thanks, Noah. I recently read an intelligent piece on Dylan by Remnick that in a cowardly if graceful manner skipped the years 1977 to 1997 because they would’ve clouded and complicated his upbeat history.

Brilliant, insightful, honest intelligent and integrous article Daniel — a deep and sincere thank you from this Nanci fan who is by now jaded and disillusioned by so much of the “music journalism” on her work. As a female music lover I also really appreciate you pointing out the ignorance of comparing Nanci with the likes of Stevie Nicks; my pet hate is that female songwriters are too often (lazily) compared to Joni Mitchell, Stevie Nicks or Kate Bush for (the ‘big three’). It makes my roll my eyes at this stage. Nanci was a fiercely singular talent who deserves more than the petty inadequacy of the New Yorker drivel.

Those are truly wonderful adjectives to see describing my work. A journalist sometimes lives without such stout praise for a lifetime, so without sounding like I am gushing, allow to say I am truly grateful.

I went to high school with Nanci at John H Reagan High School in Austin, both of us in the same year at school. I played guitar with a group of friends but Nanci was on her own. I remember seeing her one afternoon walking down the street that led away from the school under overarching trees carrying a guitar case that looked as big as she was. . .all by herself. I remember hearing her sing at a talent night at the school, and I remember the surprise when a few years late, when I was living in Oklahoma that she had put out a record, and hearing of her growing success. She had the talent, and a unique voice; and she had the purposefulness and the drive.

America does not treat well those who rise. . .but not quite to the top. We have a sick obsession with “NUMBER ONE!!!” I remember one year when the Buffalo Bills went to the Superbowl for the second year in a row against the same team, the Dallas Cowboys and lost hearing people in Texas trash talk about them, even though they had gone to the Superbowl two years in a row over every other team except one. . .that’s pathological, and that’s the way that some Americans seem to have seen Nanci Griffith. . .yeah, she was just number two. Number Two out of 360,000,000. That’s not bad, not bad at all.

One of my peeves on today’s scene is that so many gold statues go to the most popular artist, as if there is little difference between real “gold” art and Top 40 gold. I wrote a piece a year or so ago about the Kennedy Center awards sloping downhill. This year’s batch includes Queen Latifah, included partly, I suppose, to grow the viewing audience… and the fact that she’s multi-genre. There is a fear that awards ceremonies will look “elitist” if it chooses winners that aren’t massively popular, as if there is no difference between greatness and units sold. They probably, on some level, think that it’ll look anti-democratic. And there is a belief of sorts that thinks: if it gets a gold statue, it becomes great. And everyone “follows the money.”

“She states that the era of “Urban Cowboy” music was exemplified by Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard”. That alone is mind-boggling and disqualifyine.

disqualifying (😉)

I wrote a book for Nanci and we talked about that kind of journalism. Decided and brought down to basics it’s narcissism. It should not be humoured.

What an inspired idea, Dan, to take an article that pissed you off for its malice and inaccuracy and write a critique, an inspired one. Oh, the sacred New Yorker, famous forever for its magnificent fact-checking. I guess not in this case. Thanks for your essay.

“Though a beloved star with roots music fans in cities as far-flung as Boston, Austin, Dublin, and London, Griffith and her career are no doubt unknown to most New Yorker readers.” As a born and raised New Yorker, and on behalf of my nuclear and extended family and network of friends who loved Nanci and read the New Yorker, I beg to differ.