Book Review: “Disquiet” — A Compassionate Litany of Tragedies in the Middle East

By Vincent Czyz

This is a timely novel, a lament for the multicultural harmony that has disappeared from Mesopotamia as well as a dire warning: fundamentalism is on the rise, not just in the Middle East but in the West as well.

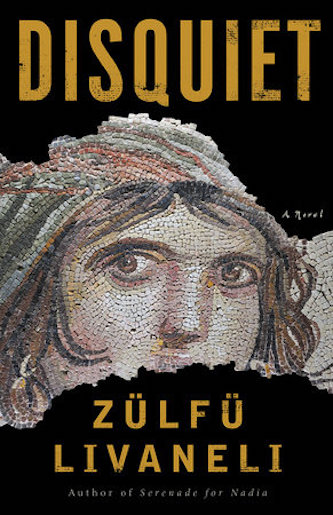

Disquiet by Zülfü Livaneli. Translated by Brenda Freely. Other Press, 176 pages, $14.95.

Everybody knows what’s wrong with Uncle Tom’s Cabin; few people, however, seem to remember how much Harriet Beecher Stowe got right. Published in 1852, it became the best-selling novel of the 19th century — and the most-talked-about work of fiction in the United States. It was responsible for the storming of a New England jail by an abolitionist mob and the death of the jailer, who’d refused to release an escaped slave slated to be returned to the South. In fact, it’s likely that Uncle Tom’s Cabin did more for the antislavery movement than all the sermons and lectures delivered by abolitionist preachers and speakers combined (as Walt Whitman might have predicted). Instead of appealing to logic, the novel dramatized the evils of slavery, giving names, faces, and voices to the slaves themselves. Stowe stoked such strong emotions, created such a stir, that some historians argue the book helped precipitate the Civil War. How many of today’s novels start riots or set armies in motion?

Everybody knows what’s wrong with Uncle Tom’s Cabin; few people, however, seem to remember how much Harriet Beecher Stowe got right. Published in 1852, it became the best-selling novel of the 19th century — and the most-talked-about work of fiction in the United States. It was responsible for the storming of a New England jail by an abolitionist mob and the death of the jailer, who’d refused to release an escaped slave slated to be returned to the South. In fact, it’s likely that Uncle Tom’s Cabin did more for the antislavery movement than all the sermons and lectures delivered by abolitionist preachers and speakers combined (as Walt Whitman might have predicted). Instead of appealing to logic, the novel dramatized the evils of slavery, giving names, faces, and voices to the slaves themselves. Stowe stoked such strong emotions, created such a stir, that some historians argue the book helped precipitate the Civil War. How many of today’s novels start riots or set armies in motion?

Zülfü Livaneli’s Disquiet seeks to do for the Yezidi people what Stowe’s magnum opus, however flawed, did for enslaved African Americans. Indigenous to parts of Iraq, Syria, Iran, and Turkey, the Yezidis adhere to a religion whose origins date back some 4000 years. Over the centuries it has taken on elements of Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Unfortunately, certain Muslim clerics identified the Peacock Angel, one of the Yezidis’ divine beings, with Satan and labeled the Yezidis themselves Satan worshipers. Thus, when ISIS militants overran Iraq, they targeted the Yezidis. Here, in the West, we heard distant echoes of “atrocities” committed against this obscure ethnic group, but we were preoccupied with events closer to home or to our own interests.

Ibrahim, the Turkish protagonist of Disquiet, is himself mostly ignorant of the Yezidis, their religious beliefs, and their plight. A well-known journalist living in Istanbul, he hails from Mardin, a hilltop city in southeast Turkey near the Syrian border. When he accidentally learns that Hussein, a childhood friend, has been murdered by neo-Nazis in Germany, Ibrahim books a flight to his hometown. The hate crime is all the more appalling since, among a gaggle of rowdy friends, Hussein was the sensitive one, a softhearted boy who “even felt sorry for the birds” the boys hunted. As an adult, he “devoted his life to the poor, the sick, and the oppressed.” In the last year or so of his life, Hussein made Syrian refugees his overarching cause. Perhaps not coincidentally, he also jilted his Turkish fiancée and married Meleknaz, a Yezidi whose young daughter is blind.

The Mardin to which Ibrahim returns is much changed. He complains of “Thousand-year-old buildings with cinderblock extensions and extra floors, tangled electric and telephone wires that looked like spilled intestines.” The changes, however, go much deeper than poor taste in architecture. Recalling “the festive days when [Christian] Assyrians, Muslims, and Zoroastrians, including Parsis, mingled in the marketplace and at school and celebrated one another’s holy days,” he notes that “now the atmosphere was closed, the city had been darkened by the shadow of a sterner, angrier Islam.”

Formally speaking, Disquiet is akin to a detective novel: it’s largely a series of interviews in which Ibrahim attempts to reconstruct the last year of Hussein’s life and profile Meleknaz, who has disappeared. He quickly learns that Hussein’s family demonized Meleknaz, insisting she’s a devil who put Hussein under a spell, and that Hussein was shot in Mardin by an ISIS sympathizer — for the crime of marrying a Yezidi — before leaving for the “safety” of Germany. From a refugee named Zilan, Meleknaz’s childhood friend, Ibrahim hears in gruesome detail what the Yezidis endured at the hands of ISIS militants.

Zilan begins with the arrival of ISIS in their village in Iraq; she and Meleknaz were 15. The men are slaughtered while the women and girls — including Zilan’s eight-year-old sister, Nergis — were kidnapped, raped, and sold into sexual slavery. The girls are divided up by different owners and separated.

“The man used me for a few days and then sold me to someone else like a pack of cigarettes,” Zilan says. “They told me that when I’d been in the beds of ten fighters I’d be a Muslim.”

The girls suffer like this for months before they are reunited, but Nergis is so traumatized she is now mute, while Meleknaz is pregnant. A Yezidi in disguise comes to their rescue, buying all three and dropping them off at the feet of a mountain range near the Turkish border. The arduous trek through this unforgiving terrain takes the girls past the bodies of Yezidis who died of hunger, exhaustion, and thirst. Nergis herself, tormented by the memories of the abuse she’s suffered, throws herself from a cliff. She dies shortly after Zilan reaches her, speaking her first words since their reunion and her last in life: “I was a human being, Sister.” Her utterance has the chilling resonance of Kurtz’s “The horror! The horror!” and becomes a refrain in Livaneli’s novel: they are also Hussein’s last words.

Author Zülfü Livaneli. Photo: Cem Talu.

“After talking to Zilan,” Ibrahim says, “everything I saw seemed like nonsense…. Whatever I did … I felt a sense of emptiness, as if there was a deep nothingness within me.” Haunted by an image of Nergis — buried by her sister and Meleknaz under a pile of rocks on the slope of a mountain — Ibrahim is pervaded by a deep disquiet.

Eventually, he gets a tip from Hussein’s brother that Meleknaz and her blind daughter, born on the barren mountainside where Nergis died, are in Istanbul. Having fallen in love with Meleknaz through rumor alone and aware that Hussein’s story is incomplete without her version of events, he returns to Istanbul, where he finally meets the elusive widow.

Despite the litany of tragedies recounted in Disquiet, the novel is less forceful than it should be. One problem is that Livaneli fails to establish Mardin as the unique location it is. Both the city and the surrounding desert get short shrift, with the result that the reader is never genuinely transported to this repository of Mesopotamian culture. (Mesopotamia, with its legacy of vanished cities and civilizations, is Livaneli’s term for the Middle East.) More importantly, however, the greater part of the story is conveyed via monologues rather than presented in-scene as the action unfolds. Even when Ibrahim is a participant, Livaneli often reduces the character to whom he is speaking to a voice. This strategy cuts Ibrahim out altogether, giving us a disembodied monologue rather than a grounded conversation. We hear what we are supposed to, but we don’t see it. Similarly, Hussein exists only in rumor and as a much-discussed memory, so his death goes more to our heads than our hearts.

Nonetheless, Disquiet is written in a lucid, compassionate style that reads well. You may find yourself polishing off this slim volume after only a couple of sittings. Moreover, it’s a timely novel, a lament for the multicultural harmony that has disappeared from Mesopotamia as well as a dire warning: fundamentalism is on the rise, not just in the Middle East but in the West as well. Hussein’s brother puts his finger on the trend when he says, “Muslim jihadis and Crusader Nazis committed a joint murder.” That is, ISIS militants shot and wounded Hussein; neo-Nazis wielding knives smeared with pig’s fat finished the job. Most disquieting, perhaps, is knowing that many of history’s tragedies, so often spawned by intolerance, were — are — eminently avoidable.

Vince Czyz is the author of The Christos Mosaic, a novel, and Adrift in a Vanishing City, a collection of short fiction. He is the recipient of the Faulkner Prize for Short Fiction and two NJ Arts Council fellowships. The 2011 Capote Fellow, his work has appeared in many publications, including New England Review, Shenandoah, AGNI, The Massachusetts Review, Georgetown Review, Quiddity, Tampa Review, Boston Review, and Louisiana Literature.