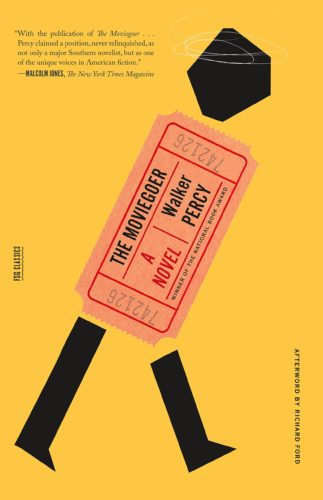

Book Review: Rereading Walker Percy’s “The Moviegoer”

By Gerald Peary

It’s Walker Percy’s subversive strategy to stick us with a decided nonhero and have us gradually appreciate his nonparticipatory status.

When I was 17, and an avid film watcher, I checked out from the library Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer, winner of the 1961 National Book Award, expecting to have a protagonist whom I could relate to. Instead, I recall finding Percy’s Binx Bolling irritating and uninteresting, a do-nothing, and I wasn’t won over by his frequent jaunts to a movie theater. And almost 60 years later? Time for another try.

When I was 17, and an avid film watcher, I checked out from the library Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer, winner of the 1961 National Book Award, expecting to have a protagonist whom I could relate to. Instead, I recall finding Percy’s Binx Bolling irritating and uninteresting, a do-nothing, and I wasn’t won over by his frequent jaunts to a movie theater. And almost 60 years later? Time for another try.

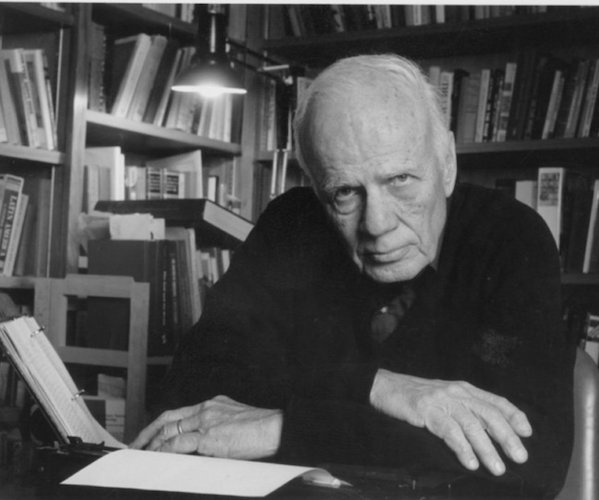

I’ve learned that Percy, a religious-minded writer, was importantly influenced in writing The Moviegoer, his first novel, by Camus and Kierkegaard. But the elements I’m concerned with in the book are much more pedestrian. What do I think now of Percy’s main character? I’ve recently visited exotic New Orleans, the setting of The Moviegoer. How does Percy, who lived there, characterize my tourist destination? Finally, as I’m almost as film crazy as I was as a teen, what does Percy, who was a moviegoer himself, have to say about cinema? Can it be a transcendent place for his protagonist as it often has been for me?

Binx Bolling is still annoying and exasperating. But now I see it’s Walker Percy’s subversive strategy to stick us with a decided nonhero and have us gradually appreciate his nonparticipatory status. I do. He’s someone who says “No” to what well-bred, white-bread Louisianans hold sacrosanct, starting with the wonderfulness of New Orleans living. He’s an outlier in a society that worships home and heritage, having a respectable education and profession, and following a prescribed life from pledging a top fraternity to enthusiastic participation yearly in Mardi Gras, joining a “krewe” of reputable locals with a float, a parade, a ball.

“I can’t stand the old world atmosphere of the French Quarter or the genteel charm of the Garden District,” Binx declares. So much for tourist New Orleans! He resides on the long-running street Elysian Fields, but as far from downtown as possible. He’s rented a basement apartment in an anonymous middle-class neighborhood called (a fictitious name) Gentilly. Binx is proud that “one would never guess it was part of New Orleans.”

True, Binx had gone to Tulane, the city’s banner university, and joined a fraternity, which seemed essential to him as a freshman. As his college years went by, indifference sank in. He sat on the frat front porch doing nothing. There was not a single activity listed in the yearbook except his fraternity membership. Under his photograph was this hapless character description: “Quiet but a sly sense of humor.

Forever after, like Melville’s Bartleby, he preferred not to.

His Garden District aunt and uncle, prominent New Orleans citizenry, are honorary royalty with thrones on Mardi Gras floats. Binx literally says “No” to participating in such de rigeur local celebration. In fact, he agrees to a Chicago business trip so he can forgo Mardi Gras altogether. When he returns home, Binx strategically misses all but the tail end of Fat Tuesday. Author Percy, with a sly sense of dark humor, offers nothing of the glories of Mardi Gras, only this grim, inhospitable, morning-after picture:

“Canal Street is dark and almost empty. The last parade, the Krewe of Comus, has long since disappeared down Royal Street with its shuddering floats and its blazing flambeau. Street cleaners sweep confetti and finery into soggy heaps in the gutter. The cold muzzling rain smells of sour paper pulp. Only a few maskers remain abroad, tottering apes clad in Spanish moss, Frankenstein monsters with bolts through their necks…”

New Orleans’s beloved fest as a 1930s Universal horror flick.

He can’t be a slacker forever. Binx’s well-to-do Garden District relatives have employment plans for him. He should partake of scientific research. “If I had a flair for doing research, I’d be doing research,” he foils their ambitions for him. “Actually, I’m not very smart.” Instead, Binx is content working for an uncle in the disreputable brokerage business. The salary is decent, he’s off at 5 pm, and he can chase after the various secretaries who come and go. Binx’s circumscribed life satisfies him: “For years now, I have had no friends. I spend my entire time working, making money, going to movies, and seeking the company of women.”

Author Walker Percy — what did he, a moviegoer himself, have to say about cinema?

OK, Binx’s constant movie-going. If a reader is anticipating a profound explanation for why he does it, look elsewhere. Binx just likes seeing movies, good or bad. It passes the time pleasantly. Here are Binx’s judgments: It Happened One Night was “very good.” The Ox-Bow Incident? “It was quite good.” As for Fort Dobbs, a 1958 Clint Walker western programmer, which he saw at a drive-in: “Fort Dobbs is as good as can be… The Moonlite Drive-In is itself very fine.”

That’s all, folks.

Only once in The Moviegoer does Binx get stirred up enough to articulate his film enjoyments: “Other people, so I have read, treasure memorable moments in their lives…What I remember is the time John Wayne killed three men with a carbine as he was falling to the dusty street in Stagecoach, and the time the kitten found Orson Welles in the doorway of The Third Man.”

We know it’s 1959 because he sees Paul Newman in The Young Philadelphians. Binx likes Hollywood movies. There is no discussion of any film not a studio one, or not made in the USA. He’s a typical 1959 fan, before the “auteur theory” came into play. He doesn’t mention the name of a single director. He knows movies by the plots and by the actors in them. He talks of “a dignified Adolph Menjou mustache” and of a “a rub of the back of my neck like Dana Andrews.” He says, “I’m no do-gooder Jose Ferrer.”

And talking about Hollywood actors: early in the book, in what could have been an enthralling episode, Binx wanders into the French Quarter and sights star William Holden, there for a film shoot, strolling down the street. Will our movie man walk up to Holden and have a spirited conversation? Perhaps about Stalag 17, or Sabrina, or Picnic? Imagine the possibilities of dialogue! And what if Holden, impressed, asked Binx to have a meal with him, perhaps at Galatoire’s? What a scene! Will Walker Percy provide it, the author’s prerogative?

No.

Holden gets a light for his cigarette from a guy passing by, and then disappears from the book. Percy makes sure that all in The Moviegoer is anticlimax, the climate for his ever-passive Binx Bolling to explain: “I have no desire to speak to Holden or get his autograph.” Or to stay in the hated French Quarter, when he can retreat to his brokerage office in the burbs and fantasize running off with his secretary.

Gerald Peary is a Professor Emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston, curator of the Boston University Cinematheque, and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema, writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: the Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty, and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His new feature documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, is playing at film festivals around the world.

Glad to have Gerry’s take on The Moviegoer, though I am an admirer of the novel and most of Percy’s other volumes, his fiction and philosophical writing. The problem is that, as Paul Elie wrote about a year ago in The New Yorker (in a piece drawn from his afterword to a new paperback edition of the book), the focus of The Moviegoer, despite the title, is not the movies:

I agree, though Bolling’s monologue also reflects a peculiarly modern spiritual predicament, a wondering inertia whose source is the post-war tidal wave of American possibility. The novel sets out to be a diagnosis, from Percy’s Catholic perspective, of a hollow psyche (a soul caught betwixt and between) paralyzed in the land of ever more, where you can be or do everything or just plain nothing. A sentence in Percy’s second novel, The Last Gentleman, sums it up: “The vacuum of his own potentiality howled around him.” In terms of black comedy — crazed American version — the line runs from Nathaniel West to Percy (as well as our unjustly maligned homegrown absurdists, John Barth, Robert Coover, and John Hawkes) to David Foster Wallace.

I recommend picking up The Moviegoer and Percy’s other books. As for the inspiration for his first novel, Hollywood wasn’t it. In an interview, Percy said it was most likely French existentialism:

Interestingly, according to Wikipedia, during the 1980s director Terrence Malick worked on a screen adaptation of the book but eventually dropped it. In December 2005, months after the destruction caused by Hurricane Katrina, Malick explained, “I don’t think the New Orleans of the book exists anymore.”

I think your comments were much more insightful than the original article. The Moviegoer is probably my favorite book mainly because I identify with the characters. The angst, the solitude, the separation from society, the existential dilemma of needing to believe in something and the reluctant desire to take a leap of faith. There was a recent article in the National Review of all things about how the book has become more relevant to our own times and uncertainty.

In many ways it is a heartbreaking book. It pops into my head often and it’s sometimes accompanied by tears. The aunt is so Southern in her stoicism and belief that you have to conform. I have read it about five times but I think about it often because I so identify. One reason, perhaps, is because I also live in the deep South or certain things were expected and either rejected or unachieved. I had a step grandmother that told me I couldn’t drop out of the Junior League (I did) and once when I bought a new house she said will surely you’re Below Broad. I said I wasn’t even below Calhoun. But she was a wonderful person and thankfully I wasn’t as close to her as Binx is to his aunt. I think it is a great piece of literature.

Hi Anne:

I obviously agree — Gerry and Matt were disappointed that they didn’t get a novel that doesn’t exist. This is a quieter, more insistently philosophical/spiritual story than a meditation on going to the movies. For me, it offers a deeper analysis of American postwar malaise than what is served up by the usual suspects, Richard Yates, Ann Beatty, et all.

The tragicomic vision of Percy and other neglected writers of the ’60s — Barth, Hawkes, Gass, etc, — serves, in one way or another, James Baldwin’s seminal insight:

We don’t like to see ourselves as monsters ….

Thanks …

I tried to get into The Moviegoer years ago since I loved its premise and was intrigued by the rather humdrum existentialism. In some ways Percy was very prescient about the idea of going to movies as a way of whiling one’s life away in an ultimately meaningless universe. After all, one must do something. I’m struck sometimes by how many moving pictures people consume these days, how matter-of-fact about consuming it they are, and the way in which it becomes a welcome distraction from, if not replacement for, living life.

I do think he had a few brilliant observations here and there (more of a philosopher than a storyteller) but nothing else has sunk in for me. Now that I actually live in New Orleans, I can’t necessarily corroborate Percy’s glum vision of it but I can say that, like a lot of legendary places, it is never quite what you expect it to be.

Percy is reflecting a distrust of images that was already part of ‘Beat’ lit. For William Burroughs, one of the ways the alien forces take over people is by addicting them to “images.” Tony Tanner noticed this in his still valuable 1971 critical study City of Words. The aliens send “false but enslaving configurations of images which prevent the receiver from establishing contact with any genuine reality either inside or outside him. In this connection, Burroughs has increasingly interested himself in films with the ultimate implication that for a lot of people “reality is actually a movie.” (“Will Hollywood never leave?” — The Exterminator.) The aliens are us. Prescient, yes?

Percy applies this notion in a less apocalyptic way in The Moviegoer, dramatizing how images insinuate (more like pollute or infect) the way we perceive the world around us. Falseness becomes second nature — the existential humdrum.

Oh, that’s definitely prescient. Might prove that Burroughs was actually the Beat whose work is more deeply relevant right now. The cut-ups, the domination by images, the obsessions with the intersection between power and sex. Lots of these insights are pretty dominant in today’s schizoid discourses.

I didn’t really get the same sense of critique from Percy, maybe I missed it, but I saw Bolling as much more essentially passive than all that. He’s not a symptom, he’s barely registering much of anything. Sure, you can be bored alienated and listless anywhere, but in New Orleans? As a non-participating local? Nah. I’d say if that’s the situation, with no occasional revelry to offset the angst, then you’re doing it wrong. Nola is certainly a haunted place– some of my students were very matter of fact about hearing similar strange sounds coming from all different corners of the quarter– and provides a wonderfully dramatic backdrop for any fiction but it seems like poor old Binx is more of a party pooper than an existential savant.

I’m with Gerry on this one. There is a pomposity in Percy’s writing that invites “serious criticism” which appealed to the literati of the time who welcomed a change from Bellow and Malamud and I.B Singer and Grace Paley, among others. The premise of the book is better than the book.

Instead of re-reading Percy find The Keepers of the House by Shirley Ann Grau which won a Pulitzer in 1965 and is a wonderful book.

Too pompous for some and too mundane for others. Given the pileup, Percy deserves a defender. American writers take a risk then they admit they are drawing on philosophical or religious ideas in fiction, particularly when they are used to critique society with black comic fervor. (There are similarities between the strategies of Flannery O’Connor and Percy in this regard.) “The Christian novelist,” writes Percy in his essay “A Novel About The End of the World,” is like a man who finds a treasure buried in a field and sells all he has to buy the field, only to discover that everyone else has the same treasure in his field and that in any case real estate values have gone so high that all field-holders have forgotten the treasure and plan to subdivide.” (Percy wrote about the end-of-the-world in 1971’s Love in the Ruins.)

To me, Percy is part of the ‘60s vision of absurdity which was taken to apocalyptic lengths by such relatively neglected writers as John Barth, John Hawkes, Paul West, William Gass, etc. But his emphasis on the breakdown as a spiritual crisis will take on interesting significance because, as novelist Amitav Ghosh writes in The Great Derangement, the challenge of the Climate Crisis will call for artists to explore collective responses in stories that push aside our currently dangerous political/technological/corporate morass. Religion (the notion of “waking up” to the existence of the sacred) may have a vital role to play in fiction that finds nature (Percy’s field) to be a treasure that must be protected and nurtured.

At this point, I don’t think it makes much sense to pit one faction against another. Bellow’s Herzog might owe something to The Moviegoer‘s examination of inauthenticity. Fifty years on, much of Percy is still in print — as is Bellow, Singer, Malamud, etc. Frankly, all of these writers, along with Updike, are no longer threatened by Percy but by a wave of critics — in and out of academia — who are sharply scrutinizing their treatment of women (or their absence). Given this cultural change, Roberta Silman’s recommendation of Grau comes at a good time. Why the superb Grace Paley has been cast aside is a mystery — Library of America are you listening? She needs to find vocal champions …

Wait – Gentilly is a real place!

I am rereading The Moviegoer now and finding the racism hard to take. It’s one thing to be Mark Twain, who has something profound to say about race, and another to be Walker Percy who seems to throw out statements about Blacks that are run-of-the mill derogatory. If Walker Percy holds different attitudes about Black folks than Binx, why doesn’t he tip his hand? I haven’t finished the book so maybe he does, but since this is not my first read, I think not.

What say you all about this?

For me, the very absence of race — or its caricature — is there to make a point. The novel is diagnostic of a spiritual illness — the emptiness of Binx and his fellow upper class Southerners is linked, in part, with their inability to see the moral degradation of the Jim Crow South. Absurdly, they can’t talk about it and won’t seriously think about it.

James Baldwin would charge that these characters are “monsters” because of this disconnection — this is conveyed through the pervasive emptiness, the sense of not being fully alive, that Binx grapples with — and never quite rises above, though his decision to go to medical school — as a service to others –suggests that he has changed for the better. Percy does not need to “tip his hand” — he is showing us a deeply sad situation — of sleepwalking through life — from Binx’s perspective.