Opera Album Review: Meyerbeer’s Comic Opera about Peter the Great, A Welcome Return

By Ralph P. Locke

This rerelease of a superb recording of a major Meyerbeer opera reminds us what treasures are available to opera companies (and college opera programs) willing to step beyond the well-trodden path.

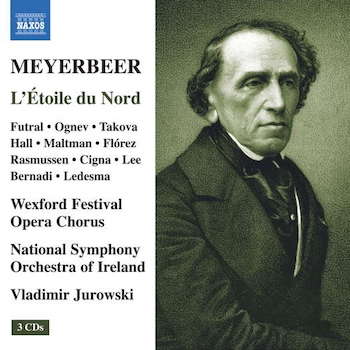

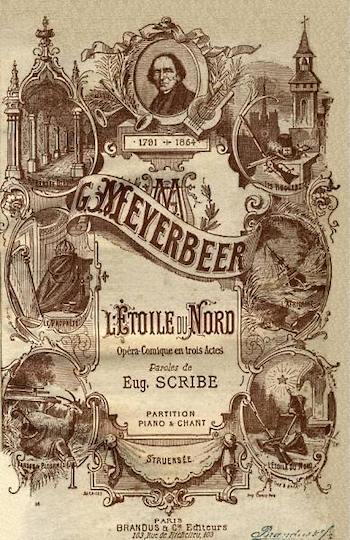

Giacomo Meyerbeer: L’Étoile du nord (1854)

Elizabeth Futral (Catherine), Darina Takova (Prascovia), Aled Hall (Danilowitz), Juan-Diego Flórez (Georges), Christopher Maltman (Gritzenko), Vladimir Ognev (Peter the Great).

Wexford Festival Opera Chorus, National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland, cond. Vladimir Jurowski.

Naxos 8.660498-500 [3CDs] 164 minutes.

To purchase and to hear the beginnings of each track, click here.

This is a rerelease of a 1996 recording that made relatively little splash when first released on the Marco Polo label. I hope it gets attention now, and sticks around in the catalogue for decades to come. It has changed my assessment of Meyerbeer, and also, quite simply, provides close to three hours of listening pleasure, thanks in large part to a collection of immensely gifted singers, some of whom (Futral, Flórez, Maltman) have, in the meantime, gone on to become superstars of the opera world, and two of whom (Takova, Hall) I am delighted to discover for the first time.

This is a rerelease of a 1996 recording that made relatively little splash when first released on the Marco Polo label. I hope it gets attention now, and sticks around in the catalogue for decades to come. It has changed my assessment of Meyerbeer, and also, quite simply, provides close to three hours of listening pleasure, thanks in large part to a collection of immensely gifted singers, some of whom (Futral, Flórez, Maltman) have, in the meantime, gone on to become superstars of the opera world, and two of whom (Takova, Hall) I am delighted to discover for the first time.

That the work has the Russia czar Peter the Great as its central character makes it all the more fascinating as an example of the profitable, if often misleading, interaction of history, myth-making, and artistic endeavor. (For a more accurate account of Peter’s life and contributions, see the clearly and engagingly written book by Yale professor Paul Bushkovitch, now in its 2nd edition.)

The average operagoer surely knows that Meyerbeer (1791-1864) wrote an important series of largely serious operas that, for over half a century, were a dominating presence in the international repertory, whether in French or in translation (most often Italian). But Meyerbeer had a gift for lighter things — catchy tunes, dance music, and operatic comedy — that crops up even in some of those serious operas: for example, the ballet music for the deceased nuns in Robert le diable; the sardonic Marcel in Les huguenots; the three chattering, if creepy, Anabaptists in Le Prophète. No surprise, then, that the two French comic operas that he composed were likewise enormously successful in their own day: Le pardon de Ploermel (also known as Dinorah) and the present work: L’Étoile du nord (“The North Star,” not to be confused with a similarly entitled work by American playwright Lillian Hellman, which also deals with Eastern Europe, specifically Soviet resistance, in Ukraine, to the Nazi invasion).

As with Meyerbeer’s other operas, only a few numbers of L’Étoile du nord (1854) continued to be known in the later 20th century. For example, portions of the extended final scene can be heard in aria CDs by Joan Sutherland, Diana Damrau, and Julie Fuchs. But the remarkable bits that have been known should have alerted us to the existence of an engaging and broadly conceived work of great staying power.

Here it is, in a recording that somehow escaped general notice but did get a warm welcome in a few places. BBC Music Magazine, for example, said that Elizabeth Futral “sings with noteworthy charm,” that the rest of the cast was “adequate if not breathtaking,” and that Jurowski’s conducting was “both vigorous and lyrical.” Vladimir Jurowski (son of the conductor Mikhail Jurowski) was only 24 when the recording was made. He has, since then, gone on to become the renowned music director of the Glyndebourne Festival, the London Philharmonic, the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, and the Bavarian State Opera. He has also conducted at the Met.

The plot derives in large part from an 1844 comic opera in German that Meyerbeer had written for Berlin, Ein Feldlager in Schlesien (A Military Encampment in Silesia), whose central character was the Prussian king Frederick the Great.

Apparently much of the music for the French work is based freely on material in Feldlager but extensively reworked, and much is entirely new. The libretto, by Meyerbeer’s frequent collaborator Eugène Scribe, makes an effective, if sometimes overcomplicated, new tale out of snippets of quasi-historical givens. The basic premise is that the young Russian czar (emperor) Peter the Great has decided to experience life by taking a disguise and presenting himself as a simple workman. A closely similar plot was used in Lortzing’s Zar und Zimmermann and in Donizetti’s Il burgomastro di Saardam, both of which put Peter in the Netherlands instead of in Finland.

The central role of Peter was written for a bass. The woman he loves, named Catherine Skowronska — a “canteen woman” (i.e., someone who provided food and drink to soldiers) — is a coloratura soprano. There is a second romantic couple: Prascovia and Catherine’s brother Georges (soprano and tenor), and a comic tenor part, the Russian pastry chef Danilowitz, that is more extensive than that of Georges. The cast includes another half-dozen roles, as well as parts for choral soloists in the many choral numbers. The whole thing is in three full acts, the first act taking place in Finland (at that time ruled by Sweden), the other two in Russia.

The central role of Peter was written for a bass. The woman he loves, named Catherine Skowronska — a “canteen woman” (i.e., someone who provided food and drink to soldiers) — is a coloratura soprano. There is a second romantic couple: Prascovia and Catherine’s brother Georges (soprano and tenor), and a comic tenor part, the Russian pastry chef Danilowitz, that is more extensive than that of Georges. The cast includes another half-dozen roles, as well as parts for choral soloists in the many choral numbers. The whole thing is in three full acts, the first act taking place in Finland (at that time ruled by Sweden), the other two in Russia.

The title (The North Star) refers to a prediction made by Catherine’s mother, back in Poland, that her fate will be governed by that reliable northward-pointing spot in the heavens. And indeed she ends up finding out that Peter is the emperor of Russia and marrying him. The historical Peter the Great did marry a servant from Marienburg (Aluksne, in what is today Latvia) whose family name was indeed Skowronska; she ruled with him for two years as Catherine I, not to be confused with the later Catherine the Great. Danilowitz in the opera is clearly modeled on Aleksander Danilovich Menshikov, who was a member of the czar’s household and later an important statesman (and for a time de facto ruler of Russia) and was (maliciously?) rumored to have been a pastry cook by origin.

The plot is elaborate, with Catherine taking disguise twice: in Act 1 as a Gypsy fortune-teller (a hoary stereotype invoked here, but at least given a positive spin) and in Act 2 (set in the Russian military camp) as her brother Georges (so that he can have two weeks with his new wife, Prascovia). She learns of a conspiracy against the current czar and, when she tries to approach Peter’s tent, the Cossack leader Gritzenko, believing that she is Georges — who is wanted for attempting to desert — orders him/her to be shot. Peter is at this point too drunk to recognize that “Georges” is his beloved Catherine. But when he sees a note that Catherine has passed to Gritzenko warning of the plot, he sobers up and reveals himself as the czar.

Act 3 winds things up no less richly. Georges quivers with (semicomical) fear that the army is looking to have him shot, and he and Prascovia agree to flee together. Soon after, Peter overhears Catherine’s voice and comes to find her, but she has lost her reason, believing that he has abandoned her. The opera ends with an elaborate multimovement scena in which moments from earlier in the opera are reenacted, complete with scenery that the characters create or assemble imitating the sets of Act 1, and Peter plays a flute tune that he remembers that Catherine loved back then. She recognizes both the tune and Peter, her reason is restored, and all hail her as the new empress of Russia. (The flute-playing bit in the plot must have worked more convincingly in Feldlager, since the actual Frederick the Great, as is well known, was an accomplished flutist and composer. Various of his works are still performed and recorded today)

None of this would matter if the music of L’Étoile were inept or routine, but it is neither. The ear is caught repeatedly by enchanting turns of phrase and harmony, imaginatively orchestrated (e.g., gorgeous high strings at the end of Danilowitz’s aria, shortly before the Act 3 finale). Some attention-holding melodies resemble ones that you may know and love from other operas written shortly before or after (e.g., by Verdi), which is just fine with me and which raise interesting questions of mutual influence (or indebtedness to a common source, such as Donizetti).

There are also heavily accented passages that are meant to sound like Russian folk music or like what Scandinavian townspeople might sing while drinking beer or whatever (drinking chorus, CD 1 track 5).

The work makes canny uses of space, as in some of Meyerbeer’s other operas: for example, an offstage bell toward the end of that drinking chorus, calling the workers back to the shipyard and thereby interrupting what was about to become a political brawl between pro-Swedish workers, on the one hand, and the two Russians — Peter and Danilowitz — on the other. Arias are often enriched by sung commentary from other characters on stage. As a result, and even more than in most Italian operas of the same era, there are a lot of words to follow here in the libretto!

The spoken dialogue on the recording has been trimmed somewhat, but enough remains to keep the plot clear. Meyerbeer also composed some passages of mélodrame — orchestral underscoring — that help make a spoken interchange extraordinarily effective.

Soprano Elizabeth Futral. Photo: Karli Cadel

The soloists vary greatly in skill and artistry. Futral (then 33 years old) is in glorious early-career shape, five years after winning the Metropolitan Opera Auditions. Aled Hall (from Wales) gets the substantial but primarily comic role of Danilowitz. With his lightweight tenor, great high notes in a kind of half-voice, and a knack for putting words across, he has lots of fun with it.

Darina Takova, from Bulgaria, is a delight to hear as Georges’s fiancée Prascovia. (Over the next decade she would take leading roles in recordings of operas by Rossini and Verdi.) As for Christopher Maltman (age 26), the role of Gritzenko sits too low in his voice for total comfort. One would not suspect from hearing this how eminent he would become in opera (the Met, Paris, etc.) and art song. But his intelligence and good vocal control do come through.

Juan-Diego Flórez, even at the early age of 23, already seems highly capable as singer and actor, but his voice is often not caught well by the microphones. Also, the part, as mentioned, is a secondary one, less attention-getting than that of Danilowitz, taken by Aled Hall. (Remember, Georges disappears from Act 2 because his sister, disguised, takes his place in the army.) Flórez’s spectacular abilities were drawing raves at other European opera houses that very year, but one would not predict a spectacular career on basis of what is heard here.

Vladimir Ognev, who received his training in Novosibirsk and has performed mostly in Russia, is gruff and, appropriately, a bit scary as Peter the Great. His tone production can be beautiful and touching when he sings high and quietly, but his coloratura is huffy. The role must have been taken with more vocal elegance and variety in early productions, such as by the great Luigi Lablache when the work was done in London.

The French text is sung and spoken effectively throughout, though of course without the numerous subtle inflections that native French singers trained in comic opera know how to introduce. Ognev’s Russian accent obtrudes, but one can partly write this off as realism. The orchestra and chorus sound small but are well tuned and respond alertly to Jurowski’s direction. The libretto and a good translation are available for free download at the Naxos site.

The recording blends three performances of a staged production in 1996 (at Ireland’s renowned Wexford Festival Opera). The audience has a grand time, understandably; their applause is, fortunately, not caught too loudly and has been trimmed to a minimum. The recording seems to have been made with just two mikes hanging over the stage to avoid picking up audience noise. We could use a studio recording now, one that allows us to hear more details in the orchestra and in the sometimes complex and overlapping writing for the voices on stage.

There is little competition. A recording that is musically less complete (starring Janet Price) was once available on Opera Rara. A 2017 video from Finland is not commercially available but can be watched online. It is staged simply and effectively (sometimes quite imaginatively, as with one scene done in silhouette). Vocally, the Peter and Prascovia are somewhat weak links, but the Catherine is splendidly accomplished. And there are English subtitles to help clarify various plot points. Taken together with the Wexford recording reviewed here, whose cast, as I’ve said, is generally capable and well-rehearsed, we can now appreciate the work’s many strengths. Like Meyerbeer’s other opéra-comique, Dinorah, L’Étoile du Nord deserves to be mentioned in the same breath as his four French grand operas.

For the curious, I would also recommend Meyerbeer’s very early German comic opera Alimelek and his Italian operas Romilda e Costanza and Il crociato in Egitto (two recordings, available here and here). The latter was composed shortly before his move to Paris — a move that was to change the course of opera history.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and is included here by kind permission.

Tagged: Giacomo Meyerbeer, L’Étoile du nord, National Symphony Orchestra of Ireland, Naxos, Ralph P. Locke