Opera CD Review: Congolese Tenor Patrick Cabongo Steps into Stardom in a World-Premiere Recording of Meyerbeer’s “Romilda e Costanza”

By Ralph P. Locke

The composer of Les Huguenots and L’Africaine was already an accomplished master at age 26, as this first-rate recording reveals.

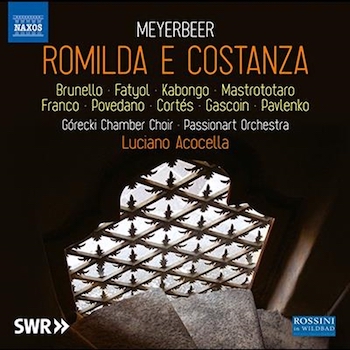

Giacomo Meyerbeer, Romilda e Costanza.

Luiza Fatyol (Costanza), Chiara Brunello (Romilda), Patrick Kabongo (Teobaldo), Emmanuel Franco (Albertone), Javier Povedano (Retello), Giulio Mastrototaro (Pierotto).

Górecki Chamber Choir, Passionart Orchestra, cond. Luciano Acocella.

Naxos 660495-97 [3 CDs] 174 minutes.

Click here to purchase.

Tenor Patrick Kabongo. Photo: David Morganti.

The arrival of a major new high tenor, capable of quick scalar “coloratura” passages, heroically flung high notes, and sweet affectionate murmurings, is always an event in the opera world. One of the latest comes from what might seem an unlikely place: the Democratic Republic of the Congo. His name is Patrick Kabongo (or, early in his career, Patrick Kabongo Mubenga). I already praised his performance of secondary roles in two Rossini operas: Maometto II and what one might call his “Passover opera,” Moïse et Pharaon. (I review the latter here.) But nothing I heard there prepared me for his splendid assumption of the leading tenor role of Teobaldo in the recently released world-premiere recording of Giacomo Meyerbeer’s Romilda e Costanza (1817). The whole opera proves to be quite a find as well, and it helps that Kabongo is surrounded by some of the most skillful specialists today in the operatic music of the early 19th century

Giacomo Meyerbeer, born and trained in Germany, got his start as an opera composer in Italy. In this he was following a path forged by German-speaking composers over the preceding century or more. Handel, Hasse, J.C. Bach, Mozart, and Johann Simon (or, in Italian, Giovane Simone) Mayr had made the same pilgrimage, sometimes to gain further training, other times to compose directly for a particular theater, court, or church.

In Italy, Meyerbeer gained success with a half-dozen operas, beginning with the one that here gets its world-premiere recording, Romilda e Costanza (1817), and continuing with such notable examples as Margherita d’Anjou (1820) and Il crociato in Egitto (The Crusader in Egypt; 1824). Il crociato was produced not only in Italian theaters but in Paris and London, and its success in Paris led to Meyerbeer’s relocating to that city. There he made history with a series of grand operas — including Les Huguenots (1835) — that became standard items in the international repertory for close to a century.

Romilda e Costanza is a “melodramma semiserio,” which means that it features some comic characters (e.g., Pierrotto—recognizable in part by the diminutive version of his name, suggesting lower social class) and that it ends up happily for all. Rossini’s La gazza ladra and Matilde di Shabran are other instances of this interesting and today sometimes-puzzling genre; a better-known one is Bellini’s La sonnambula.

The plot used in Romilda e Costanza is an intriguing variant of the “rescue opera” type that opera aficionados know about from such instances as Grétry’s Raoul Barbe-Bleue and Beethoven’s Fidelio. Here the unjustly imprisoned person is male (Teobaldo, tenor), and not one woman but two seek to release him: his current sweetheart, Romilda, and his former but still faithful one, aptly named Costanza.

The artful libretto by Gaetano Rossi (frequent librettist also for Rossini and, later, Donizetti) makes the most of the complications here, which involve Costanza and Romilda having to overcome their competitiveness for the affections of Teobaldo. There is some interesting confusion along the way: not least, Romilda first shows up in disguise as a young page (i.e., male), which Meyerbeer made plausible by setting the role for alto. (The faithful Costanza is a soprano.) What at first seems to be Romilda’s entrance aria (CD1 track 14) quickly gets joined by Costanza and Teobaldo in a gorgeous trio-movement of emotional complexity (“Che barbaro tormento”) — a movement that reportedly became the best-known number in the opera.

The superb booklet essay, by musicologist Sieghart Döhring, helpfully explains some of the ways in which this first of Meyerbeer’s six Italian operas already goes beyond the Rossini operas that it otherwise strongly resembles. I think I noticed, though, one borrowing from Rossini that is a bit too close: a march motive that runs through CD2 track 9 (“Ma, cos’è questo?”) seems to have been lifted directly from the opening of the Act 1 finale of The Barber of Seville (which had been a big hit a year earlier), matching it even in the way it modulates. I couldn’t help hearing a supposedly drunken soldier (Count Almaviva in disguise) throwing the door open and crying “Hé!”

Particularly notable throughout the opera is the orchestration, which is treated with more variety — quicker shifts and contrasts — than in Rossini’s operas of the same period. This is a testament no doubt to the symphonic achievements of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, which Meyerbeer had clearly studied during his years of training in his native Germany. Intriguingly, a rising series of parallel chords in the strings near the end of the overture seems to predict a moment in Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, though I don’t imagine that Berlioz knew this particular opera of Meyerbeer’s.

Particularly notable throughout the opera is the orchestration, which is treated with more variety — quicker shifts and contrasts — than in Rossini’s operas of the same period. This is a testament no doubt to the symphonic achievements of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, which Meyerbeer had clearly studied during his years of training in his native Germany. Intriguingly, a rising series of parallel chords in the strings near the end of the overture seems to predict a moment in Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, though I don’t imagine that Berlioz knew this particular opera of Meyerbeer’s.

The singers — from widely diverse countries including Mexico, France, Italy, and Romania — are all capable or much more than that. The weakest in the main roles is Giulio Mastrototaro, who is apparently older than the rest, having sung in the festival’s recordings made in 2006-8. His unsteady delivery and approximate pitch are no more welcome here than they were in Rossini’s aforementioned Matilde. But his humorous (manipulative, etc.) delivery is clearly apt and, in front of an audience, must have helped enliven the several important scenes in which he is present, including an extended duet with Romilda in Act 1.

Enormously welcome, as the hero Teobaldo, is aforementioned Congolese coloratura tenor Patrick Kabongo. After getting his start at home, he received extensive further training in Brussels, and has made his career with major opera houses in Paris, Rouen, and Strasbourg. Here he rises to the challenges of a leading role, and the audience is clearly thrilled. I look forward to hearing the confident tones of this dramatically alert singer in future productions. His coloratura is elegant and faultless.

The title roles are taken effectively by soprano Luiza Fatyol (as the rejected Costanza) and alto Chiara Brunello (as new gal Romilda). Meyerbeer’s decision to assign the roles to singers with distinctly different ranges helps us distinguish them throughout the opera, especially because Brunello here has a darker tone than Fatyol, even when the two sing in roughly the same range. Each is quite accomplished in coloratura and becomes, if anything, even more impressive as the opera goes along. (A singer’s voice frequently increases in flexibility as it warms up.) Their multimovement duet in Act 2 (end of CD2) would be a great way to sample this opera. It can be heard for free on YouTube (here is the slow section), as indeed can each track from the recording.

You can even compare there the aforementioned trio movement for Teobaldo and the two women (“Che barbaro tormento”) to a previous recording of that marvelous movement, featuring Chris Merritt and two little-known but fine singers, Bronwen Mills and Anne Mason (on the Opera Rara label; this trio recording is likewise on YouTube). The orchestra is just a bit more polished and more vividly present in the Merritt-et-al. recording, and the coloratura singing is a touch cleaner there (often true in studio recordings). But in the new, complete recording of the opera one gets a stronger sense of dramatic interaction among the three characters: the tempo adjustments and the women’s energetic performance of the scalar swoops near the end prevent the number from feeling, as in the Opera Rara recording, like a highly refined vocal concert.

I was also pleased to encounter again here the baritone Emmanuel Franco (who impressed me greatly in Rossini’s Matilde).

The whole recording is, like most from Naxos, available on Spotify and other streaming services. The beginning of each track from the recording can be conveniently tasted here. And you can download the libretto and booklet for free from Naxos.com.

Conductor Luciano Acocella in action. Photo: Naxos.

The Passionart Orchestra, a group from Kraków (Poland), became the resident ensemble at the Rossini in Wildbad festival in 2019. It plays just as well as did the Moravian orchestra that held the same contract for years. The winds are perhaps even better tuned, though the solo violin in one aria here (CD 1, track 6) is insecure, not remotely up to the level of the rest of the group. (Couldn’t this have been rerecorded and inserted?)

The Górecki Chamber Choir sings with superb tone and balance, though they sound uninvolved in the dramatic proceedings. Was this an unstaged performance? I hear no stage noises, nor do the soloists seem to move around.

The conductor, Luciano Acocella, keeps up a smart pace, yet adapts tempos appropriately. Fortepianist Andrés Jesús Gallucci makes the secco recitatives specific to the situation and, with his occasional semi-improvised right-hand commentaries, musically engaging.

Döhring’s wonderful booklet-essay is printed in type too tiny for aging eyes. The synopsis is detailed and includes track numbers (hurrah!). The Italian-only libretto carefully indicates in paler print any lines of recitative that have been omitted in performance. But I wish that Wildbad and Naxos would also translate the libretto, especially when an opera is as unknown as this one.

This much-needed release will give opera lovers and music historians lots to think about and lots to enjoy. I hope the Wildbad festival rebounds. The festival originally scheduled for 2020 was postponed and, according to recent announcements, will indeed take place on July 8-25, 2021, in performance venues that are suitably safe (e.g., outdoors).

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Giacomo Meyerbeer, Luciano Acocella, Naxos, Patrick Cabongo, Ralph P. Locke, Romilda e Costanza

[…] From Meyerbeer, we get his early Romilda e Costanza (and also his even earlier German opera Alimelek, a comic opera based on the tale of “the sleeper awakened,” from the 1001 Nights). […]