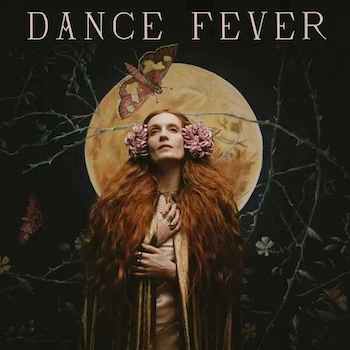

Pop Album Review: Florence + The Machine’s “Dance Fever” – Inside the Artist’s Mind

By Henry Chandonnet

Dance Fever is one of the few pandemic-themed artworks that doesn’t feel contrived — it is specific about the value of music to the individual and by extension to the community.

The introspective pandemic-era project has already become a cliché. Sure, a reevaluation of life, society, and how we define ourselves is always a fruitful artistic endeavor. Still, the genre has become overpopulated with the same tropes about overcoming solitude and the importance of other people. This is not a new idea — thousands of years ago Aristotle said we were social animals. So, for an artist to explore the urge to escape isolation, there must be a fresh approach. Florence + The Machine pulls this off in their new album, Dance Fever, by investigating the nature of performance itself.

The introspective pandemic-era project has already become a cliché. Sure, a reevaluation of life, society, and how we define ourselves is always a fruitful artistic endeavor. Still, the genre has become overpopulated with the same tropes about overcoming solitude and the importance of other people. This is not a new idea — thousands of years ago Aristotle said we were social animals. So, for an artist to explore the urge to escape isolation, there must be a fresh approach. Florence + The Machine pulls this off in their new album, Dance Fever, by investigating the nature of performance itself.

In this album, lead singer Florence Welch questions why we create art, focusing on the phenomenon of “choreomania,” a European social mania where individuals felt the urge to exhaust themselves by dancing. Welch finds this lunacy inspiring, drawing on it to ask (and then answer) the question of why we dance, perform, and revel. She does so by creating tracks that deliver the kind of bliss that might drive listeners into a state of euphoric distraction.

Of course, dancing until you drop has its hazards, to life and limb. Welch takes this up in her song “Choreomania,” aptly named for the project’s obsession. Over flurries of rhythmic claps and exasperated breaths, Welch sings about dancing herself (and others) into the grave: “The pressure and the panic / You push your body through / Something’s coming, so out of breath / I just kept spinnin’ and I danced myself to death.” Here music controls the body, pushing it to the point of pain. Art and mortality are linked, which makes music more than pleasure — it is dangerous. Taking that risk is personal, and Welch confronts this wager in some of the album’s most remarkable lyrics: “You said that rock and roll is dead / But is that just because it has not been / Resurrected in your image?” This question reverberates throughout Dance Fever. Performance is seen as an agonizing process; creation is about searching for truths, no matter how harrowing the quest. In this sense, the record is an exercise in meta-songwriting — Welch comments on music-making as she makes it.

So what is the payoff for the artist? For Welch, creativity is about experiencing complete freedom. In her song “Free,” Welch dramatizes her belief: “Is this how it is? / Is this how it’s always been? / To exist in the face of suffering and death / And somehow still keep singing?” As the dance-pop beat rises, and her bridge swells to a crescendo, she reaches a realization: “But there is nothing else that I know how to do / But to open up my arms and give it all to you / ‘Cause I hear the music, I feel the beat / And for a moment, when I’m dancing / I am free.” Appropriately, this is the liveliest track on the album, its swift drum beat building to an ecstatic release with “I am free” chanted over a synth melody.

It is at this point in the album that Welch turns her attention to the effects of Covid-19 on creativity. The theme of music as freedom is seen as valuable to others because of its value as liberation, a kind of therapeutic promise. When her performance is isolated from others Welch feels as if she is trapped within herself. In the song “Girls Against God,” Welch croons, “Oh, it’s good to be alive / Crying into cereal at midnight / And if they ever let me out, I’m gonna really let it out / When I decided to wage holy war / It looked very much like staring at my bedroom floor.” Over shrill cries and repeated harp flourishes, Welch laments what life would be like without her performing music. What might have come off as a self-aggrandizing sob story — she is performing up a storm in this tune — feels justified, given how previous songs have dramatized how singing frees Welch from her own body. In this way, Dance Fever is one of the few pandemic-themed artworks that doesn’t feel contrived — it is specific about the value of music to the individual and by extension to the community.

By the end of the album, Welch has made her message clear: art is a physical release from inner demons, a laborious and painful process that provides a necessary release. Her final song, “Morning Elvis,” epitomizes this belief: making art is more than a joyous pastime — it is salvation. As swelling harmonies grow to an apex, Welch chants, “Oh, you know I’m still afraid / I’m still crazy and I’m still scared / But if I make it to the stage / I’ll show you what it means / To be spared.” Welch must make her art and she must perform it because it saves her. And by saving herself, she helps others deal with their Covid-19 traumas. The pandemic was all about loss, the erasure of things and people we believed we couldn’t live without. We all are just trying to “make it to the morning,” as Welch puts it, staggering toward a way of life that we may never have again. That longing is mitigated as we hear how Welch has renewed herself. She can perform again, and her songs dramatize her triumph: Welch has surmounted pain and yearning and has attained ecstasy, salvation, survival.

Henry Chandonnet is a current student at Tufts University double majoring in English and Political Science with a minor in Economics. On-campus, he is an Arts Editor for the Tufts Daily, the preeminent student-run campus publication. You can reach out to him at henrychandonnet@gmail.com, or follow him on Twitter @HenryChandonnet.

[…] Online Arts Magazine: Dance, Film, Literature, Music, Theater, and moreMay 26, 2022 Leave a CommentBy Henry ChandonnetDance Fever is one of the few pandemic-themed artworks that doesn’t feel […]