Listening During Covid, Part 11: Making Classical Music New in All Kinds of Ways

By Ralph P. Locke

Two exquisite sopranos bring us refreshing songs, arias, and cantatas; and a noted Broadway composer and a remarkable Black librettist offer a searing opera about police brutality.

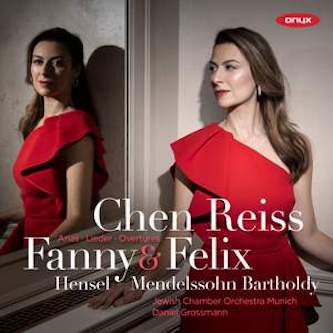

Fanny & Felix Mendelssohn: Arias, Lieder, Overtures. Chen Reiss, soprano, and the Jewish Chamber Orchestra Munich, cond. Daniel Grossman. Onyx 4231—65 minutes.

Trennung: Songs of Separation. Carolyn Sampson, soprano, and Kristian Bezuidenhout, fortepiano. Bis-2623—73 minutes

Blue (music by Jeanine Tesori; libretto by Tazewell Thompson). Briana Hunter (Mother), Aaron Crouch (Son), Kenneth Kellogg (Father), Gordon Hawkins (Reverend), Washington National Opera, cond. Roderick Cox. Pentatone PTC 5186-967—122 minutes.

To purchase, click here for: Trennung, Fanny & Felix Mendelssohn, or Blue.

I often like to be entertained and challenged by classical music, not comforted by yet another once-over of familiar sounds.

But, as regards Covid, I’m still a Nervous Nellie (or Nervous Nelson, being a him-pronoun person). So no concerts for me yet, nor any Metropolitan Opera transmissions in the movie theater.

Fortunately, the record companies are more than meeting my need for fresh pleasures and adventures. This installment of “Listening During Covid” treats three releases, each of which involves music that is mostly unusual, or performed in unusual ways, or both — and all deeply satisfying.

The best-known name here is that of Felix Mendelssohn. Lyric soprano Chen Reiss (her first name means “Grace” in Hebrew) and conductor Daniel Grossman pair several very disparate works of Felix’s with pieces by his immensely accomplished composer-sister Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel. Eight of Fanny’s songs, originally for voice and piano, soar and glow here in stylistically appropriate orchestrations by Tal-Haim Samnon. Two of the eight were originally published under Felix’s name because it was considered unseemly at the time for a middle-class woman to be selling her wares — even if those wares were settings of poems by, say, Goethe.

The best-known name here is that of Felix Mendelssohn. Lyric soprano Chen Reiss (her first name means “Grace” in Hebrew) and conductor Daniel Grossman pair several very disparate works of Felix’s with pieces by his immensely accomplished composer-sister Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel. Eight of Fanny’s songs, originally for voice and piano, soar and glow here in stylistically appropriate orchestrations by Tal-Haim Samnon. Two of the eight were originally published under Felix’s name because it was considered unseemly at the time for a middle-class woman to be selling her wares — even if those wares were settings of poems by, say, Goethe.

Song lovers will be fascinated to hear Hensel’s thoughtful take on “Die Mainacht” (The May Night), a sweet-sad Ludwig Hölty poem better known through Brahms’s highly evocative setting. We hear a remarkably dramatic concert aria — “Infelice!” — by Mendelssohn, and a no less vivid “dramatic scene” by Hensel, based on the ancient Greek legend of Hero and her secret lover Leander. The important violin solo in “Infelice!” is played by the renowned soloist Arabella Steinbacher.

The CD is completed by two excerpts from Fanny’s “Lobgesang” cantata (not to be confused with Mendelssohn’s “Lobgesang” Symphony) and an early version of Mendelssohn’s overture “The Hebrides (Fingal’s Cave)” that is as satisfying in its own way as the revised version that music lovers rightly hold dear.

Reiss sings exquisitely and meaningfully throughout, as she did in a collection of Beethoven songs and arias that I reviewed here. The Jewish Chamber Orchestra Munich sounds lean and sweet (and beautifully tuned), and also, at crucial moments, forcefully passionate. (For an interview with soprano Reiss about Fanny Hensel that is much more informative than the somewhat odd CD booklet, click here.)

Carolyn Sampson is one of the most-often recorded lyric sopranos of our age, best known in oratorio and in art song. Her latest CD is entitled Trennung, from one of the many beautiful songs on it, Mozart’s “Das Lied der Trennung” (“Song of Separation”). The songs, all of which deal in some way with love sundered, or at the least made painful by distance, are by a varied batch of composers from across the 18th century, including Mozart and Haydn but also — in order of birth — Wolff, Fleischer, and Herbing. Gosh, composers back then knew how to write gratefully for the voice and characterfully for the keyboard! Of course, it helps that there’s such a superb artist as Sampson singing, and that her collaborative pianist is Kristian Bezuidenhout, renowned for his many recordings, solo and with orchestra (including Mozart’s and Beethoven’s concertos). You can feel singer and keyboard player listening to each other and interacting, pausing ever so slightly, nudging a tempo, and often pointing out thereby interesting felicities in the poetic text. Bezuidenhout plays a modern copy of an 1805 Viennese instrument that is a pleasure to hear and superbly responsive.

The 2019 opera Blue yanks us forcefully into our own day. It tells the tale of a Black policeman (called simply The Father) whose teenage son gets shot to death during a protest against — the bitter irony — police brutality. We come early into the story, meeting The Mother (likewise African American), when she admits to her Girlfriends — I use the opera’s terminology — that she “married a cop” and reveals that she is pregnant. We see The Father interact with his three Policemen buddies (“Welcome to the daddy club!”). We witness The Father forcefully reminding The Son how to dress so as not to be targeted (“take off the hoodie”). And we experience the agony of the couple in the aftermath of their son’s murder. In a powerful epilogue they recall the last words their son said to his father: “I can’t [be home] this weekend…. One more, a silent protest. Nothing will happen. You could come with me. Nothing will happen. Nothing….”

The 2019 opera Blue yanks us forcefully into our own day. It tells the tale of a Black policeman (called simply The Father) whose teenage son gets shot to death during a protest against — the bitter irony — police brutality. We come early into the story, meeting The Mother (likewise African American), when she admits to her Girlfriends — I use the opera’s terminology — that she “married a cop” and reveals that she is pregnant. We see The Father interact with his three Policemen buddies (“Welcome to the daddy club!”). We witness The Father forcefully reminding The Son how to dress so as not to be targeted (“take off the hoodie”). And we experience the agony of the couple in the aftermath of their son’s murder. In a powerful epilogue they recall the last words their son said to his father: “I can’t [be home] this weekend…. One more, a silent protest. Nothing will happen. You could come with me. Nothing will happen. Nothing….”

The music is by Jeanine Tesori, best known for her score of Caroline, or Change, the 2003 Tony-winning Broadway musical about a Black maid working for a middle-class Jewish family. The libretto is by the renowned stage director Tazewell Thompson. The opera was first performed, fully staged, at the Glimmerglass Festival, but the recording was made by the Washington National Opera (with most of the same singers) under studio conditions, and with a certain amount of physical distancing, in June 2021. YouTube has several valuable videos of excerpts and explanations from the composer and the librettist (here and here) and from opera scholar Naomi André.

Tesori’s music is engaging and memorable. Echoes of blues, jazz, and gospel styles recur, not least in several powerful scenes in Act 2, in which The Father and The Mother confront — or hide from — the vastness of their loss. There’s definitely some Motown in the scene of The Girlfriends.

Tesori says that she listened repeatedly to a recording of Thompson reading the libretto, in order to capture his intended inflections. She succeeds marvelously. It helps that the singers on the recording of Blue are so intensely communicative. Most have secure voices (though Kenneth Kellogg as The Father is less steady than the rest) and put the words across well. The one big name in the cast is Gordon Hawkins, a world-renowned Porgy, Rigoletto, and Alberich, who here establishes a rock-solid presence as The Reverend.

Blue is surely one of the best new operas to have been written in North America (I don’t know ones from elsewhere) in the past dozen years. I’d put it up there with Mexican-born composer Daniel Catán’s Il postino (2010, in Spanish; available in a DVD featuring Plácido Domingo), Scott Wheeler’s Naga (2016, with Anthony Roth Costanzo), and Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones (2019; it opened the Met’s 2021-22 season, with a cast featuring Angel Blue, and has been shown on PBS).

Anybody who tells you that classical music is too predictable, specializing in retreads, isn’t listening to what I’ve been listening to!

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich).