Visual Arts Review: Color on Plaster – Frescoes from Pompeii in New York

By David D’Arcy

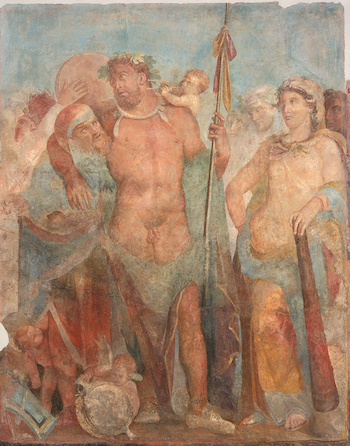

Hercules and Omphale in the Pompeii in Color exhibition. Photo: ISAW

If you are in New York this week there is plenty of art to see. Just a short walk from the Metropolitan Museum is a show that you will probably never see again. You can visit it for free. It closes this weekend.

The show, barely noticed by the press, is Pompeii in Color: The Life of Roman Painting, a wondrous selection of paintings from more than 2,000 years ago, at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World of New York University.

If you have visited the Greek and Roman Galleries of the Met, you have probably seen a few such images from frescoes — where paint was applied to fresh wet plaster — but not the variety of more than 30 works on view in this exhibition.

These pictures decorated houses and interiors in Pompeii, which was covered in volcanic ash in 79 BC. At first glance, these images might strike you as hallucinations in muted colors: they seem faint at first. Look at them for a longer time and figures in these paintings take on an uncanny presence. We see mythological scenes and families at home. There are groups of airborne erotes (cupids, the putti of the Roman empire) and still lifes in colors that are still seductive after 2,000 years.

The exhibition has two versions of Achilles on the island of Skyros. The story behind these scenes is not included in Homer’s Iliad. A prophecy decreed that the Greeks would subdue Troy, but Achilles was fated to be killed in campaign. In order to spare him, the young man’s mother, Thetis, sent Achilles to Skyros and had him dressed as a girl. The Greeks, led by Odysseus, seize him there and take him off to war. One painting of Odysseus’s arrival looks like an ensemble of portraits of the characters involved, including the women of the court where Achilles was disguised. Another picture captures the drama of Achilles being abducted by the Greeks — destiny is thrown into motion.

History, mythologized or not, is not always dignified. Pompeii is best known — beyond the art world — for its erotica. The paintings in Pompeii in Color were shown inside homes, often by their owners to guests, in gatherings where wine flowed freely. No surprise, drinking is often the subject of paintings. So are drunks.

An image that visitors won’t forget, and not just because it is the largest and among the best-preserved in the exhibition, is of Queen Omphale of Lydia (now in Turkey), who buys Hercules — yes, Hercules — at a slave market, and exchanges clothes with him when he’s drunk. The hapless tipsy Hercules, stripped to below the waist and held upright by an old man, stands alongside Omphale, who wears his garments and signature lion’s skin. She is also holding his club — guess what that refers to. She looks a lot like the Italian film actress Anna Magnani as she glances at his body, which glows from the wine he’s consumed. In the Renaissance, some 1500 years later (and ever since), Hercules is usually depicted as a triumphant hero. Not so in this meeting with Omphale: an impertinent child blows pipes in the warrior’s ear while other erotes taunt the man as they play. The enormous Hercules seems too drunk to notice.

The Three Graces in the Pompeii in Color exhibition. Photo: ISAW

Colors throughout the show tend to be subdued, no surprise after two millennia, yet probably less muted than they would have been if Pompeii hadn’t been buried under ash for so much of that time. In sculptures from the period, which would have been painted then, we see (with rare exceptions) the chilling hue of marble.

We can particularly appreciate the use of color in The Three Graces, adolescent figures that are known to us from antiquity (originally from Greece) and from the many depictions (mostly in sculpture) that have come down to us since then. In paint, now shady, the three girls are intertwined, sculptural enough so we feel the balance of their poses, yet painted with delicate skin tone and ambiguous expressions that would have been near-impossible to be duplicated on stone. The scene’s resonance is all over Western art, from Cranach to Canova. I thought of the poker-faced girls in Georges Seurat’s The Models (“Les Poseuses”) from 1886-88 at the Barnes Foundation. Visitors to the show are sure to make their own associations.

This is the exhibition’s second stop in the United States. It opened in a slightly different version in Oklahoma City; a video made there is a helpful introduction.

The Met, nearby, plans an exhibition on the painted sculpture of antiquity, and that will be a revelation to those accustomed to looking at figures of bare stone. That show opens July 5. The exhibition to take in first is Pompeii in Color. It closes Sunday.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.