Gospel Album Review: Sister Rosetta Tharpe — A “Solid Sender”

By Michael Ullman

I admire Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s wit and daring, her singularly effective guitar playing, and the subtlety of her singing.

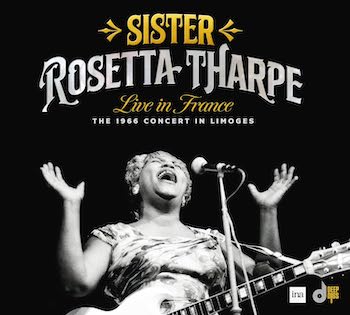

Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Live in France: The 1966 Concert in Limoges (two LPs: Elemental Records)

Sister Rosetta Tharpe was called “the godmother of Rock and Roll” so many times it must have hurt. She was a pioneer, not a precursor. Born Rosetta Nubin in Arkansas in 1915, Tharpe took her last name from one of her husbands, but tweaked it, so she would be forever known as Tharpe rather than that forgotten man’s “Thorpe.” She refused to be pinned down. Her mother was a gospel singer and Rosetta grew up singing with her in churches and church events. As a young adult, already married once, she moved to New York. She made her first records in 1938 at the age of 23. They made her a star. In one of her songs she says of Jesus: “He give me a guitar, I’m going to play it, he’s my friend.” Her talent was, she thought, a gift. A friend said of the Tharpe: “She would sing until you cried and then she would sing until you danced for joy. She helped to keep the church alive and the saints rejoicing.”

Sister Rosetta Tharpe was called “the godmother of Rock and Roll” so many times it must have hurt. She was a pioneer, not a precursor. Born Rosetta Nubin in Arkansas in 1915, Tharpe took her last name from one of her husbands, but tweaked it, so she would be forever known as Tharpe rather than that forgotten man’s “Thorpe.” She refused to be pinned down. Her mother was a gospel singer and Rosetta grew up singing with her in churches and church events. As a young adult, already married once, she moved to New York. She made her first records in 1938 at the age of 23. They made her a star. In one of her songs she says of Jesus: “He give me a guitar, I’m going to play it, he’s my friend.” Her talent was, she thought, a gift. A friend said of the Tharpe: “She would sing until you cried and then she would sing until you danced for joy. She helped to keep the church alive and the saints rejoicing.”

She sang gospel over her own nimble, bluesy electric guitar in clubs as well as churches. She played with and recorded some of her earliest hits with the big band of Lucky Millinder. These included “Shout, Sister Shout” and the blues tune Bertha Hill made famous in 1926: “Trouble in Mind”. The crossover disturbed some of the faithful, whom I suppose we would now call the gospel police. Ira Tucker of the famous quartet the Dixie Hummingbirds put the objections this way on a PBS special: “It was like a bomb had dropped on gospel music when she flipped, … It was hurtful to a lot of people, because they felt as though they had lost something. They had something, and it was great, but now it was gone. They viewed it almost like a death.” She wasn’t deserted by her fans altogether: in 1950 an estimated 20 to 25 thousand of her enthusiasts packed Washington D.C.’s Griffith Stadium to witness her third marriage. They were treated to a concert afterwards. Wedding or no wedding, Tharpe didn’t want to miss a day of work.

I admire Tharpe’s wit and daring, her singularly effective guitar playing, and the subtlety of her singing. Tharpe was daring. In 1938 she made her hit recording “Rock Me.” By then, hundreds of recordings had already been made using “rock me” as a metaphor for sex. “Rock me with a steady roll” was a typical line. (In the early ’70s I talked to Texas bluesman Mance Lipscomb, who was shocked that little girls talked about “rock and roll.”) “Rock Me” begins with a beautifully lyrical guitar solo — it is both relaxed and rhythmically alert. At one point, Tharpe plays a fast run, stops with a zippy chord, and adds a wobbly series of bent notes. It’s an example of instrumental wit. Singing in her brash style with a tight vibrato, she calls on the Lord to “Wash my soul with water from on high, and to “rock me in the cradle of your love.” “Hold me in the hollow of your hand,” she says, as if the Lord were both a comfort and a good buddy. Her later hits include 1939’s “This Train,” and “Down by the Riverside”.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe performing in Cafe Society in 1940. Photo: Charles Peterson

Tharpe’s early records are widely available, but I find this two LP set invaluable because it teaches us, among other things, how brilliantly she handles a crowd. The audience in Limoges seems knowledgeable: she gets them clapping cleanly on beats 2 and 4. A man yells out a request for “Beams of Heaven,” one of the more obscure numbers in her repertoire. The sweet clarity of her playing, its rhythmic variety, is omnipresent. She hints at current issues, using comedy effectively. “Well,” she sighs, people are “always talking about us women.” The women in the audience giggle. She shen introduces the famous gospel song, “Jesus Met the Woman at the Well” in a daring way. “This man,” she says, “may have been good-looking, we don’t know.” Suddenly the scene at the well seems … flirtatious. She infuses the oft-married woman at the well with humanity. The woman at the well, Tharpe tells us in a mock whisper, spies “this fine man…from nowhere.” “May I have some of your water,” this stranger asks. Tharpe enjoys acting out the response: “Umm…well” she says in her most seductive tones. Then she bursts into an especially slow, dramatic vocal, with swoops, whispers, and shouts. “Woman, woman., you have well said” begins the stranger as he excoriates the not-so-innocent woman. Tharpe wrly adds blues-driven decorations of the melody. She moves between a whisper and a shout as Jesus points out: “The one you got now is not yours.” (Keep in mind that Tharpe had three husbands herself.)

The concert begins with a reprise of Tharpe’s hit “This Train” via a restrained version. She had to warm up. Later she sings a comic gospel song (there are such things, she tells us) called “Moonshine.” Tharpe introduces “Down by the Riverside” with a verse I hadn’t heard before. When she gets to the familiar (and wonderful) melody, she rocks it. The crowd starts clapping after the singer shouts and improvises: “Well,well, well ..” She follows “Riverside” with “When the Saints Go Marching In,” pushing the crowd into clapping by pounding her foot on the stage and yelling “Oh yes.” She then plays a chorus on guitar. In the heat of the moment she almost growls out a chorus. God is her protector and her goal: “If anybody bother me, I’m going to tell Jesus.” Jesus has been good to her: “He give me a guitar, I’m going to play it, he’s my friend.” She admonishes as well as challenges us when she revs up to sing :”If we only loved one another, we’d be fed on two little fishes and five loaves of bread.” That’s instead, she adds amusingly, of our usual diet of pork chops and cornbread.

The woman who once recorded “I Want a Tall, Skinny Papa” ends this concert with “Give Me That Old Time Religion” and “If Anybody Bother Me.” Jesus told her “to walk on,” a significant command in that era of demonstrations. Her last number is the sober “Nobody’s Fault But Mine”. She opens “Nobody’s Fault” with a long, held note on the single word, fault. We get the moral message. Performing early and late in her career with “peace and love in her heart,” Sister Rosetta Tharpe was what musicians called a “solid sender”.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bimonthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: Elemental Records, gospel music, Live in France: The 1966 Concert in Limoges