Book Review: “The Recent East” — Exploring Seldom Seen Territory

By Drew Hart

Thomas Grattan, a New Yorker with German roots, displays an observant eye and a way with dialogue in his first novel.

The Recent East by Thomas Grattan. MCD/Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 368 pp., $13.99.

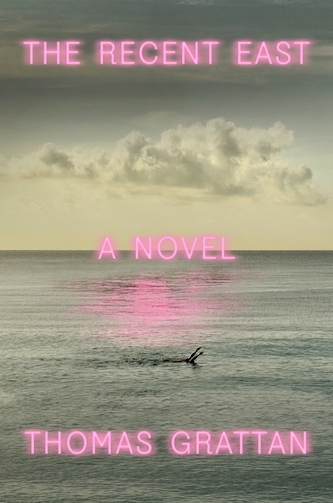

Consider the title of Thomas Grattan’s debut novel and then its cover art, which depicts a lone swimmer out in a somber ocean. They suggest a tale of mystery, without spelling anything out. At first, the puzzle seems to be rooted in political intrigue, but then the story becomes a generational saga. But again, it’s wise to check any assumptions at the door when it comes to this undertaking and its notable ambiguities.

Consider the title of Thomas Grattan’s debut novel and then its cover art, which depicts a lone swimmer out in a somber ocean. They suggest a tale of mystery, without spelling anything out. At first, the puzzle seems to be rooted in political intrigue, but then the story becomes a generational saga. But again, it’s wise to check any assumptions at the door when it comes to this undertaking and its notable ambiguities.

It’s 1968 as The Recent East opens; the “east” under consideration is that which was once communist East Germany. Rarely depicted — the film The Lives of Others is one of few examples that comes to mind — the country and its society are grim and repressive, a police state built on a complicated network of spies and informants. Unsurprisingly, a highly educated professor is seen making arrangements to flee. Viewed from the perspective of his 13-year-old daughter, Beate, their successful escape is facilitated via expensive forged passports. Enduring a chilly interrogation scene, these dissidents land in West Germany and later move to America.

And then — what was that we were saying about assumptions — time abruptly shifts. You could liken the sequencing of this story to viewing something through a prism, as it flashes back and forth over what ultimately turns out to be nearly 50 years. Next it is 1990; the Berlin Wall has fallen, and a grown Beate, whose marriage to an American has ended in upstate New York, is returning with her own two teenage children to repatriate in Germany, where their ancestral house has been sitting empty for decades in a quiet Baltic town. The former East Germany is empty and in disrepair; they move into the home with nothing but sleeping bags. Beate’s son Michael scours other abandoned houses in their neighborhood for furniture, while his studious and idealistic sister, Adela, who’s one year younger and often mistaken for his twin, pores over books that chronicle the country’s tarnished past. Soon a long-lost cousin of Beate’s, Liesl, appears to help them settle in; she has a son, Udo, who befriends Michael and Adela, and before long they are inseparable.

These are the characters that form the core of things here, as the tale swoops in and out of time. We see a new Germany rising out of the ashes, still haunted by its history. Nazi skinhead gangs and Bosnian refugees appear in town and, inevitably, clashes develop, including one which alienates Adela from her cousin — who takes sides against the immigrants and drunkenly engages in a rock-throwing incident. She decides to return to her father, who has moved to California. Meanwhile, Beate finds herself giving haircuts to former Stasi police operatives in a local bar: she works in a nursing home and has entered a short-lived second marriage. Michael, who has explored his gay instinct ever since coming to Germany, becomes a libertine, juggling partners in clandestine sexual encounters.

Later, it’s 2009, and Michael has opened a lively bar where customers play “Truth or Dare”–like games and confess secrets from the communist era. Udo, now remorseful for his violent offense, has settled into a job as a contractor in which he tries to hire foreign help. He too has an unsuccessful marriage, which leads to despair and a death while boating that may or may not be intended. Adela has married a doctor in California and then moved with him to a life in South Africa dedicated to relief work among AIDS victims. She returns to Germany with a young son, Peter, and winds up staying for a while, helping Michael run his barroom. Ironically, she’s not there when he is badly beaten up by a rowdy gang. Ultimately, the narrative settles in 2016: Adela has been in Washington, finding herself remarried; Michael is owner of several popular restaurants in what is now a prosperous seaside town; young Peter, who may be considering sexuality as his uncle did, is extremely close to grandmother Beate, who we see selling her family home, making plans to scale life down.

Regardless of whatever grand historical highlights are covered by The Recent East, it’s more significant to note the novel’s smaller detailings, which are laid down well. You’re looking at a nuanced fabric in which a vision of everyday doings seem to be the larger point. This intelligent, quirky family, moving through time and change, remains strongly connected, devoted to one another throughout. Grattan, a New Yorker with German roots, has an observant eye and a way with dialogue. It would be interesting to know just what led to the book’s writing — he’s exploring seldom-seen territory — as it will be to find out where he turns his attention to next.

Drew Hart writes from Santa Barbara, California

Much of Jonathan Franzen’s Purity is set in East Germany. It gives a fairly in-depth look at East German society,

Thanks for a fine review. I’ve added this book to my reading list.