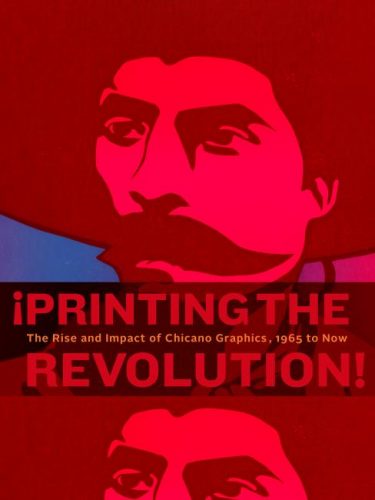

Book Review: “¡Printing the Revolution! — The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now”

By Tim Francis Barry

There’s a looseness, a jagged brio that gives the images in ¡Printing the Revolution! a visual bang — a kind of primal pop.

¡Printing the Revolution!: The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now, with essays by Claudia E. Zapata, Terezita Romo, E. Carmen Ramos, and Tatiana Reinoza. Edited by E. Carmen Ramos. Princeton University Press, 344 pages, $49.95.

Published in association with the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC. Exhibition Schedule Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC — Reopening 2021, Dates TBD

Should there be a revision to Mount Rushmore, I propose chipping away enough stone to add the face of Cesar Chavez. In contrast to his heroic counterpart, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., labor-organizer Chavez was uneducated and toiled in grape fields for little money under withering conditions. He lived the poverty-stricken life that he eventually fought to change. Like Dr. King, Chavez went beyond bringing attention to the piteous plight of his people: he was adept at rallying thousands to the cause. When Chavez began organizing the Mexican-American and Filipino pickers in 1962, their lot was dire. It was a crucial segment of what Michael Harrington in his landmark book called The Other America.

Should there be a revision to Mount Rushmore, I propose chipping away enough stone to add the face of Cesar Chavez. In contrast to his heroic counterpart, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., labor-organizer Chavez was uneducated and toiled in grape fields for little money under withering conditions. He lived the poverty-stricken life that he eventually fought to change. Like Dr. King, Chavez went beyond bringing attention to the piteous plight of his people: he was adept at rallying thousands to the cause. When Chavez began organizing the Mexican-American and Filipino pickers in 1962, their lot was dire. It was a crucial segment of what Michael Harrington in his landmark book called The Other America.

Living in shacks without electricity, running water, or sanitation, brown workers were paid 90 cents an hour, out of which they needed to buy their own food. Chavez took to the streets in protest, arguing that at the very least they should make the national minimum wage, at that time $1.25 an hour. The growers stonewalled, so the protesters marched from California’s Central Valley the 300-miles to the capitol in Sacramento. Eventually the International Farm Workers union was founded, and conditions improved … somewhat.

This not-enough-known chapter in American history is one of the many political/economic struggles of the underclass visually and vividly brought to life in the poster exhibition and handsome book ¡Printing the Revolution!: The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now. Is it worth questioning whether political posters can be appreciated as ‘art?’ On the one hand, there’s artistry involved in the design and execution of posters. But then graphic-design and decision-making talent can be found in street signs, gum wrappers, and on the label on your soy sauce bottle: “lower sodium” and “All Purpose.” And, just as the La Choy Co. is selling you on the benefits of it’s condiment, so you have political groups pushing an agenda — trying to sell you on their party line or call to action.

It is a knotty critical problem; whether the didactic and aesthetic can be happily co-joined. Polemical art often falls short artistically in its single-minded quest to shout out a message. But, like album cover graphics, movie posters, rock concert t-shirts and even neon signs, some political posters rise to the level of art. Maybe not Fine Art — of the type traditionally shown in conventional art museums — but the times they are a’ changin’. Museums are scrambling to attract a new generation populated by a cyber-jaded demographic with shows that feature fashion and David Bowie ephemera. The Museum of Modern Art teamed up in 2015 with the singer Bjork. As for ideology, 70% of millennials polled in 2019 said they’d be somewhat or extremely likely to vote for a socialist candidate.

So rather than grump about the days of yore, when Picasso was all the rage, let’s examine the considerable appeal of what is being shown today. There’s a lot to admire in this exhibition of mostly very angry Chicano and Latinx posters. Wielding the bright, eye-popping color traditions of Mexican graphic art — infused in many cases with ironic humor and biting vitriol — many of these posters also rock the Southern California contemporary art vibe.

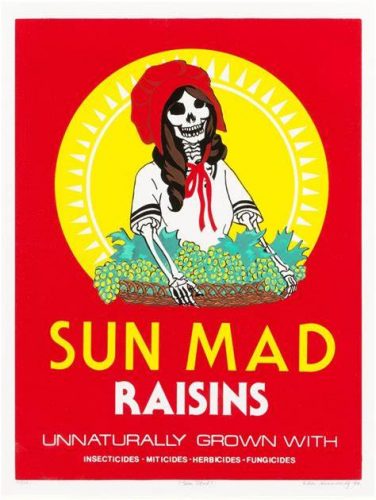

Ester Hernandez, “Sun Mad,” 1982. Photo: Smithsonian American Art Museum.

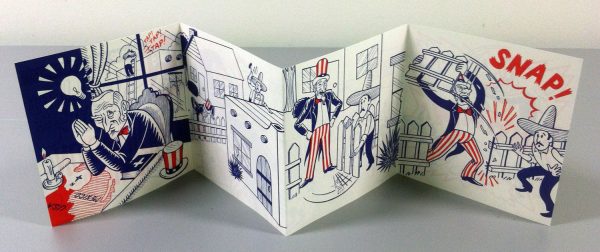

Case in point: Ester Hernandez’s Sun Mad (1982), in which she takes a page from the Pop Art playbook to convert a Sun Maid raisins box into a funny and vivid commentary on the plight of California’s beleaguered grape picker population. Or there’s Julio Salgado’s 2014 screenprint Quiero Mis Queerce, which takes a hard look at the problems facing undocumented queer youth. Eric J. Garcia’s Chicano Codices: Simplified Histories proposes a sort of People’s History of Mexico via a series of slyly subversive but simple graphic drawings. These codices are inspired by the example of pre-Columbian codex, a political/aesthetic strategy that asserts a historical through-line.

The rise of Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 gave the exhibition coordinators an opportunity to be up-to-date; they have included some BLM sign imagery. In truth, this material does not measure up in its graphic power to the Chicano material, though does provide a valuable context in which to draw attention to kindred protests happening around the country, including the struggles among low wage workers (such as, among a number of examples, employees at Amazon) to form unions.

The accompanying catalogue to the exhibition is well-executed; its essays ponder the nuances of graphic design in the context of political protest, and dig deeply into the ‘hidden’ history of Mexican-American culture. For example, the very term Chicano morphed from a racial slur into a proudly uttered badge of heritage, in much the same way Black supplanted Negro a few years earlier in the ’60s. This rejection of the homogenizing impulse behind calls for melting-pot assimilation is summed up in a poster that depicts a Mayan warrior figure with the word “Pilgrim” underneath.

The most contemporary part of the exhibition focuses on the intersection of latinidad with issues of race, gender, class, and sexuality. To be sure, these are zeitgeist driven and worthy pursuits. If the thrust of the book and exhibition comes off as more preachy than radical, well, it is the Smithsonian after all. It’s charter is ‘art museum,’ but the institution’s primary focus is Americana. And, at this point in time, the agenda of the modern museum is about entertainment (albeit the enjoyment is delivered mostly online at the present moment.)

The look of the (mostly) poster art in ¡Printing the Revolution! is some cases garish — day-glo is the hue of choice — but that is understandable given that these pictures are mostly announcements for events, not gallery-bound works of fine art. And, of course, bright colors have been at the core of Mexican political art since Diego Rivera decorated Rockefeller Center back in the 1930s (which was later painted over because of its Communist imagery).

Eric J. Garcia’s Chicano Codices Presents: Simplified Histories: The U.S. Invasion of Mexico

Much of the art here skews toward the street variety, hand-drawn and quickly sketched, which explains the absence of such iconic Latinx political art figures as Daniel Martinez and Los Carpinteros, whose work comes out of a conceptual art tradition. Most of these posters draw on a ‘one-idea, one-picture’ strategy that’s about sending a forceful, unmistakable message, and there is something refreshing about the directness — no theory-based visuals here. The word ‘primitive’ is not the right fit for these images, given how much skill is evident. Still, there’s a looseness, a jagged brio that gives them a visual bang — a kind of primal pop.

Tim Francis Barry studied English literature at Framingham State College and art history at the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth. He has written for Take-It Magazine, New Musical Express, Noise, and Boston Globe. He owns Tim’s Used Books, located in Provincetown and Northampton.

[…] Read More from artsfuse.org […]