Book Review: “The Death of Vazir-Mukhtar” — A Formalist Critic’s Picaresque Novel

By Laurence Senelick

A new complete translation of the most accomplished novel by Yury Tynyanov, an innovative Russian man of letters during the experimental 1920s.

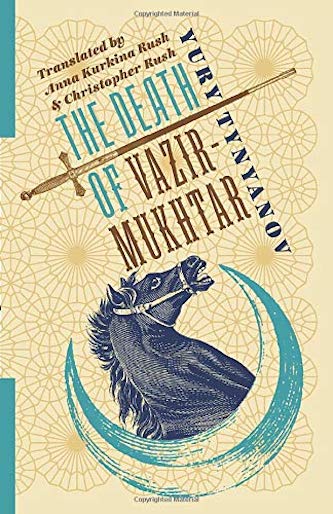

The Death of Vazir-Mukhtar by Yury Tynyanov. Translated by Anna Kurkina Rush and Christopher Rush. New York: Columbia University Press, 2021. xxviii, 599 pp. Softbound. $19.95.

The name Yury Tynyanov will, in this country, mean nothing outside of university Slavic departments and well-read émigé communities. There he may be vaguely recalled as an innovative Russian man of letters during the experimental 1920s, but his unavailability in translation has proven a barrier to wider acquaintance. This may change with the appearance of a new complete translation of Tynyanov’s most accomplished novel, The Death of Vazir-Mukhtar (1927).

Better-known is his novella Lieutenant Kizhe, made into an ingenious film (1934) for which Tynyanov wrote the screenplay. Set in 1800, in the reign of mad Tsar Paul who treated his army like toy soldiers, its action derives from an error made by a copying clerk in a list of military promotions. He takes the plural –ki and the emphatic particle zhe to be a proper name; and so Second Lieutenant Kizhe is born. This phantasmal being, accused of disturbing the emperor’s rest, is flogged, exiled to Siberia, recalled, promoted to general, married to a lady-in-waiting, showered with money; ultimately he dies, is buried and mourned by his sovereign as “his best officer.” Kizhe’s invisibility at these events is attributed to his being “a secret agent without a profile.”

The soundtrack for this Gogolian satire was composed by Sergei Prokofiev, who later refashioned it into a much-performed suite. This in turn was chosen by Alec Guinness for the soundtrack to his high-spirited screen adaptation of Joyce Carey’s novel The Horse’s Mouth. And there we have the six degrees of separation between Yury Tynyanov and Star Wars.

Academics tend to be less interested in Tynyanov (1894-1943) as a novelist than as a theorist and critic connected with the Formalist movement. Put simply, the Formalists were opposed to the tendentious demand of traditional Russian criticism that an author be engaged in civic betterment, preferably in the realistic mode. The Formalists concentrated on the devices that composed a work of literature and stressed its essence as an artifact. Their most famous tenet was Viktor Shklovsky’s concept of ostranenie, “making it strange.” A writer’s task was to lure the reader into seeing the ordinary or the overlooked with new eyes. Hence their favorite author was Gogol.

For Tynyanov, text is the central object of literary criticism, which has to maintain a scientific edge, studying genres rather than themes or content. The words, speech patterns, stylistic devices matter more than sociopolitical, biographical or historical context. He scorned the “life and times” school of literary biography, for he thought a writer’s life as much a product of his writing as the writing may be a product of his life.

Unfortunately, after Stalin came to power in 1925, such ideas became not so much unfashionable as lethal. With socialist realism legislated as the only permissible, the only authorized style, to be labeled a “Formalist” was to be denied publication and an income, if not worse. Imaginative Soviet writers took refuge in children’s stories, translations and, in Tynyanov’s case, biography. To preserve his critical tenets, he recast facts as fiction. This also allowed him to fill in the lacunae left by history with his own speculations

Tynyanov drew his heroes from the 1820s, for, like them, he was obsessed with the so-called Decembrist revolt. In 1825 Nicholas I came to the throne, having sidelined the true heir, his brother Constantine. On the first day of his reign, a group of noblemen and officers held a demonstration calling for a constitution. Nicholas put it down brutally; the ringleaders were hanged or exiled to Siberia, and those suspected of complicity, which meant many of Petersburg’s best and brightest, were punished by banishment or imprisonment. The tsar rapidly turned the Russian Empire into a police state, annexing Transcaucasia, Poland, and Moldavia in the process.

Tynyanov’s trilogy of novels centers on a constellation of writers caught up in the “uprising” and its aftermath: the rebellious poet Wilhelm Küchelbecker, jailed for his participation; Aleksandr Pushkin, exiled for his suspected involvement; and A. S. Griboedov, arrested for his associations. With Pushkin, Tynyanov had to confront what every Russian thought he knew about the national poet, and that novel was left unfinished. With the other two, he was dealing with relatively unknown quantities and could fabulate to his heart’s content.

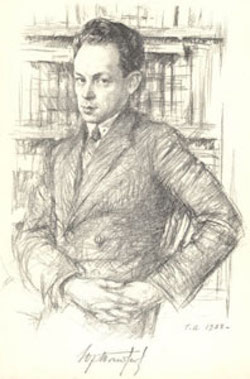

Yury Tynyanov. Photo: Wiki Commons

As Auden wrote, “a shilling life will give you all the facts.” Aleksandr Sergeevich Griboedov, born 1795 (probably), to minor nobility. Excellent education, Moscow University. Dabbles in writing light comedy, in collaboration or by adaptation from the French. 1817 begins to serve in the Foreign Office as a provincial secretary. Fights a duel in which his thumb is grazed. Exiled to the embassy in Tehran (1818-22), where he helps draft a peace treaty. Vacationing in the Caucasus and Central Russia writes Woe from Wit, the greatest verse comedy in Russian; unpublished and unperformed in his lifetime. Late 1825 arrested in Tiflis (now Tbilisi) on suspicion of involvement with the Decembrists, briefly jailed, exonerated, sent back to Tehran to enforce the terms of the treaty. On the way marries a teenage Georgian princess. Sketches out drafts of plays. 1829 the Russian compound is stormed by a mob stirred up by fanatic mullahs. Torn to pieces, tossed in a ditch.

Griboedov left few letters, no memoirs; manuscripts were destroyed during the storming of the embassy. His personality has to be constructed from the recollections of his acquaintances and his likes and dislikes conjectured from Woe from Wit. There is a plethora of documented context for the period, however: into this overcrowded canvas Tynyanov fits Griboedov’s tabula rasa and proceeds to scribble all over it.

Tynyanov begins his tale in the fifth act of his hero’s short life. Civil service, duel, writing, love affairs, exile are all in the past. Consequently much of the novel consists of fragmentary memories, allusions to unseen figures, references to bygone events. Much is this is left unexplained or unglossed. Scenes reconstructed in detail seem peripheral to the general design. At a time when the Stalinist Writers’ Union demanded straightforward narratives, so as not to confuse the newly literate, Tynyanov deliberately thwarts and frustrates those who read for plot. At the same time, he regularly plants signposts of Griboedov’s ultimate fate, suffusing the novel with a pervasive mood of foreboding.

Tynyanov’s Griboedov is not an immediately sympathetic hero. His careerist ambitions are regularly undermined by his indecisive and vestigial idealism. Impassive yet calculating, modest yet self-involved, aspirational yet procrastinating, he comes across as a very 20th-century brand of hero, Musil’s Man without Qualities. His writhing in the toils of two monstrous court bureaucracies, Russian and Persian, brings Kafka to mind. Within the Russian tradition, he seems an amalgam of Pushkin’s Onegin and Griboedov’s own Chatsky, outsiders traveling to forget. Throw in dashes of Turgenev’s superfluous man; Goncharov’s sofa-bound Oblomov; Chekhov’s constipated heroes, well-intentioned but torpid. What all these intelligent gentlemen have in common is an inability to achieve anything constructive. When Griboedov does take action, the results are disastrous.

The book falls into two distinct halves. In the first Griboedov, smarting from a number of reversals in his career and his personal life, is dubious about taking on the government assignment to Persia. His mission is to get the Shah to pay the arrears on the peace treaty Griboedov had had a hand in drafting years before; he is also ordered to repatriate a colony of army defectors now serving the Persians. The scenes are set in Petersburg and Moscow, familiar from so many sources, abuzz with intrigues in high society and government circles.

In the second half, Griboedov sets out, like a disillusioned Quixote with his body-servant Sashka as Sancho, to fulfill the mission. He has been given an empty title, Minister Plenipotentiary, or in Farsi, Vazir-Mukhtar. He loiters in sybaritic Tiflis, where he marries the teenage Nino Chavchavadze and dreams of a life of domestic bliss; then off to various cities and villages in Iran, where the intrigues of court eunuchs, English diplomats, Russian turncoats, and his own taciturn nature bring about his doom. At times, Griboedov’s decisions and hesitations seem to be moves in a deliberate suicide. After what sometimes comes across as a leisurely and digressive travelogue, the last chapters gather speed and intensity. To a reader of our time, the sudden violence of the jihad, its origins and aftermath, have a gruesome familiarity.

Yury Tynyanov by G. Vereyskiy (1928, Leningrad). Photo: K.A. Fedin State Museum.

Despite Tynyanov’s disdain for themes in literature, one of his earliest critics, Prince Dmitry Mirsky, identified a theme running through this novel, that of betrayal. Soured by the failure of the Decembrists, many of the characters betray their ideals. Griboedov himself betrays his promise as a writer by becoming a government agent and then betrays his various conflicting goals. He is constantly betrayed by his superiors, colleagues, and most fatally by circumstance.

Much of the singularity of Tynyanov’s treatment of history surfaces if we compare it with War and Peace. Tolstoy’s viewpoint is Olympian, sweeping over a panorama; even taking into account its animus against Napoleon and the great-man theory, it claims objectivity. Tynyanov’s treatment is close-focus, moving from one consciousness to another, leaving gaps in the characters’ understanding of what is happening. Instead of one godlike narrator who reads into the minds of his creations, we have a swarm of purblind agents trying to make sense of their individual situations.

For all Tynyanov’s screenwriting, it may be too trite or too facile to describe his style as “cinematic,” as Anna Britlinger does in her introduction to this translation. There is nothing cinematic about whole pages purporting to be copied from a doctor’s journal or snatches of folk songs and Persian poetry quoted at random. “Joycean” might be more appropriate. The sudden shifts of viewpoint, the jostling of public pronouncements with private apprehensions, the occasional stream-of-consciousness, the salacious interest in concubinage and castration, the parody of literary tropes, the juggling with foreign languages — all point to an accidental kinship. They are both so steeped in their subjects that they go into writerly overdrive.

Tynyanov did his homework and its shows. There are so many characters both delineated and mentioned that the translators have had to provide a biographical glossary of around 250 names. In his story “’Savonarola’ Brown” (1920), Max Beerbohm introduces a would-be playwright who spends a lifetime writing a verse drama about the Florentine monk. Parodying those writers of historical fiction who drop names as local color, one stage direction reads:

Re-enter Guelphs and Ghibellines fighting. SAV[ONAROLA]

and LUC[REZIA BORGIA] are arrested by Papal officers.

Enter MICHAEL ANGELO. ANDREA DEL SARTO appears

for a moment at a window. PIPPA passes. Brothers of the

Miseracordia go by, singing a Requiem for Francesca da

Rimini. Enter BOCCACCIO, BENVENUTO CELLINI, and

many others, making remarks highly characteristic of them-

selves…

Tynyanov’s novel has many such moments, to wit:

The guests sat in a row: Pyotr Karatygin, tall and discerning,

red-faced, the Bolshoi Theater actor and jack of all trades; a

young musician Glinka, next to a shaggy and sharp-nosed

Italian; the brothers Polevoi, wearing their merchant-style

frock-coats and light-colored neckties with big tiepins.

The ladies were represented by the affectedly grimacing

Varvara Danilovna Gretsch, or “Gretschess” as Faddei

[Bulgarin] called her; the pockmarked little Dyurova,

Pyotr Karatygin’s wife — a French woman whom Faddei

nicknamed “Froggy”; and, of course, Lenochka in a

stunning outfit.

The names Brown drops are at least recognizable to most educated persons; Tynyanov’s ring a distant bell largely with specialists. And this is only a third of the way into his book. By the time we get to Tabriz and Tehran, these tangles of proper names stop the narrative dead in its tracks.

Dramatist Aleksandr Sergeevich Griboedov

The translators also append a dictionary of foreign terms and phrases, since Tynanov shows off his linguistic prowess by studding the narrative and the dialogue with Persian, Georgian, and Tatar words, not always explained. This quickly annoys as an affectation, wooing the exotic at the cost of clarity. Perhaps obscurity is the intent; however, it may be the verbal equivalent of the fog of unknowing in which the characters grope their way. Why should the reader be exempt? It may also be a means of ostranenie, of making the past strange and unfamiliar. Tynyanov’s devices constantly keep readers at bay, preventing them from slipping into a cozy repose, lulled by the rhythm of “and then, and then, and then.” For all its immersion in plot and counter-plot, Dan Brown this is not.

Oddly enough, after languishing in Anglophone obscurity for decades, the novel appeared in 2019 in a British translation begun by the late Susan Causey and finished by Vera Tsareva-Brauner. I haven’t seen it and so cannot use it as a gauge of comparison. The American translators Anna Kurkina Rush and Christopher Rush are to be commended for their devotion to their author. They have sought equivalents for every archaism, period term, or outlandish word. They do not quail before Tyayanov’s most obscure references. They turn verse into verse and annotate assiduously, rather than planting their notes in the text (mostly). I have some trifling cavils: tabak, in context, ought to be rendered “snuff” rather than “tobacco,” and bakenbardy “side-whiskers” rather than “sideburns.” What they call “truffle pie” is pâté de Strasbourg. For all their diligence and ingenuity, however, Tynyanov remains elusive: he toys with various styles, parodies familiar tropes, and even applies the skaz technique of a colloquial narrative embedded in the larger structure. It would take an English writer of equivalent virtuosity to convey this verbal abundance with brilliance. Absent a more audacious approach, the translation reads as a translation, accurate, praiseworthy but flat and uneven, like much of the terrain Griboedov has to cover.

Laurence Senelick’s books include Russian Dramatic Theory from Pushkin to the Symbolists; A Historical Dictionary of Russian Theatre; and A Documentary History of Soviet Theatre. He has translated The Complete Plays of Chekhov (W. W. Norton), as well as works by Gogol, Bulgakov and others.

Tagged: Anna Kurkina Rush, Christopher Rush, Laurence Senelick, The Death of Vazir-Mukhtar

Anna and Christopher Rush are NOT American…Anna is Russian and Chris is a Scot…