Opera Review: Thomas Adès’ “Powder Her Face” — Scandalously Relevant

Powder Her Face proved the perfect capstone to Odyssey Opera’s month-long survey of British (mostly comic) opera: biting, darkly humorous, provocative, and relevant.

Ben Wager and Amanda Hall in the Odyssey Opera production of “Power Her Face.” Photo: Kathy Wittman.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

In hindsight, it’s almost like it had to end with fishing rods. Near the close of Thomas Adès’ 1995 opera Powder Her Face, the story’s protagonist, known simply as the Duchess, is about to be evicted from the hotel room in which she’s been living for some time. As she laments the emptiness of her life and her impending demise, out of the orchestra pit rises the sound of one, then two, then three, and, finally, four fishing rods, inevitably reeling her to her fate, as it were.

In terms of orchestration, it’s a brilliant stroke; psychologically, it’s rich; and, in Sunday’s finale of Odyssey Opera’s exceptional summer festival, “The British Invasion,” at the Boston Conservatory Theater, the gesture came off with subtlety, irony, and a surprisingly emotional payoff. In the event, Powder Her Face proved the perfect capstone to Odyssey’s month-long survey of British (mostly comic) opera: biting, darkly humorous, provocative, and relevant. What more could you ask for from the most dramatic of art forms?

For its narrative, Powder Her Face takes, with a few minor liberties, scenes from the life story of Margaret Campbell, the Duchess of Argyll. Her sensational divorce trial from her third husband (the Duke), which ran between 1959 and 1963, brought to public attention her numerous affairs (which were documented by some graphic photographs, a few of which were projected onstage during the opera’s sixth scene) and generally hedonistic lifestyle. Librettist Philip Hensher didn’t shy away from anything: the text is filled with suggestive dialogue and double-entendres, orbiting around an explicit (though in Odyssey’s production, discreetly-handled) depiction of oral sex at the end of Act 1.

And the brash, acerbic libretto is matched line-for-line by Adès’ kaleidoscopic score. The music embraces the avant-garde but never loses sight of the purpose of its raucous sound world and gestures; rarely has such musical complexity sounded so, well, populist and accessible or served such clear, dramatic ends. Written for just four voices (taking seventeen roles) and an orchestra of fourteen (playing roughly fifty instruments between them), Powder Her Face fragments and distorts a host of familiar musical idioms, tangos and popular song styles among them. The instrumental ensemble serves as a kind of Greek chorus, commenting on the action with shrieks, sighs, grunts, and occasional snarling laughter. The vocal writing is highly acrobatic and rhythmically complex. The result is an opera that demands fearless singers who can act; an audacious pit band; and balanced, even-handed stage direction.

Odyssey had all that and then some in soloists Patricia Schuman, Ben Wager, Daniel Norman, and Amanda Hall; the reduced Odyssey Opera Orchestra; and, especially, in stage director (and scenic designer) Nic Muni. Muni’s set placed the opera’s action all within the Duchess’ hotel room. Each scene was announced with projections of newspaper headlines and photographs from the year in which the action occurred (spanning from 1934 to 1990). His thoughtful, straightforward direction of the singers kept the action moving smoothly and let the music and characters speak for themselves.

The other members of the production team played key roles, too. Linda O’Brien’s subtle lighting design added psychological and emotional depth, especially during the final couple of scenes in each act. And Amanda Mujica’s costumes and Rachel Padula Shufelt’s hair and make-up designs transformed the three singers taking multiple roles (only Schuman, as the Duchess, sang one part) convincingly and, often enough, humorously.

Odyssey’s singers were all very well cast. Adès and Hensher clearly don’t have much sympathy for the Duchess – her egocentrism and vanity are never far from view between the opera’s opening scene and its last – but, in Patricia Schuman’s heroic account of the part, there were moments towards the end that evoked a kind of sympathy for this tortured woman. Schuman sang with power and lustrous tone, projecting an aristocratic bearing throughout her scenes, especially as her character became increasingly unhinged.

As her opposite, the Duke (also the Hotel Manager, Laundryman, Other Guest, and Judge), baritone Ben Wager also made a strong impression, stentorian in some roles (like the Duke and Judge), more sweetly lyrical in others.

If there was a standout among these four superb singers, to these ears it belonged to Amanda Hall, whose clarity of tone and precision of pitch and diction didn’t falter throughout the evening. Whether cackling with laughter as the Maid, lamenting her plight as the Waitress, commenting on the divorce proceedings as a Cockney Rubbernecker, or interviewing the Duchess as the Society Journalist (here done up as Gloria Steinem), Hall’s singing was intense and focused; she’s one to watch.

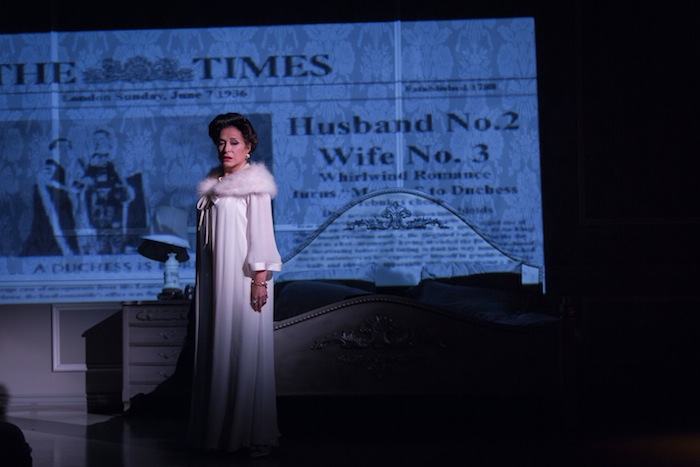

Patricia Schuman in the Odyssey Opera production of “Powder Her Face.” Photo: Kathy Wittman.

And Daniel Norman, with his sweet-toned tenor, was no slouch in any of his myriad roles, whether suggestively mocking the Duchess as the Electrician, crooning a soft-shoe number as the Lounge Lizard, or receiving the Duchess’ favors as the Waiter.

In the pit, Gil Rose drew a precise, riotously colorful account of the orchestral score. Adès’ instrumental writing at times bears the mark of a young composer not fully experienced in writing to accompany voices onstage: ensemble numbers can sound a bit cluttered and some bursts from the pit cover the Duchess during her final aria. But the instrumental parts are never dull and Rose balanced his ensemble just about as well as could be hoped for. If all of the text didn’t come across as clearly as it might have, that owed more to Adès’ demanding writing than anything else: the gist of Hensher’s libretto came over well enough (though supertitles could have helped the audience delve into its layers of meaning).

It should perhaps come as no surprise that the finale of such an invigorating and satisfying festival as “The British Invasion” be so compelling. Still, for marriage of production concept and direction, musical execution, and visceral drama, Odyssey’s Powder Her Face was as convincing an operatic presentation as I’ve seen anywhere. You don’t necessarily expect that from a company that’s not yet reached its third birthday, but that’s the level that Odyssey is working at, even now. It’s exciting to be in a city where one can experience such things.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: British Opera, Gil-Rose, Odyssey Opera, Power Her Face