Film Review: A Quartet of Discoveries at the Provincetown International Film Festival

Reviews of four strong independent films that may — or may not — be coming to a screen near you.

By Tim Jackson

Film festivals are one of the best ways to experience the rich variety of films being made by independent directors — before distributors decide what’s best for audiences to see. In the case of the Provincetown International Film Festival, that means sorting through movies with humanist themes or that shine a light on LGBT culture. Here are some discoveries that may — or may not — be coming soon to a screen near you.

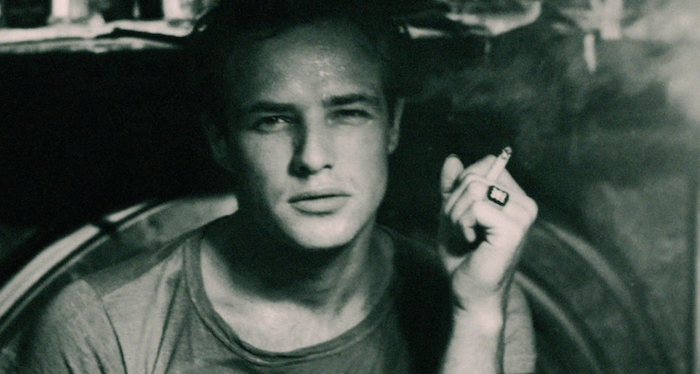

A scene from the documentary “Listen to Me Marlon.”

Listen to Me Marlon

Marlon Brando kept an archive of audiotapes and this documentary (directed by Stevan Riley) draws on these recordings to create a unique confessional profile of the actor. The tapes are filled with opinions and ruminations; they are also chockfull of self-hypnosis sessions. Brando was troubled by a lot of things: an abusive father, his own fame, troubled relationships, his negligence as a parent, acting as a craft, and the hypocrisy of the movie industry in general. Predictably, the monologues leave a lot of questions unanswered. The film acknowledges this with its opening shot of Brando, who is reciting lines from Shakespeare, his rotating and fuzzy head an incomplete digitized image (apparently his noggin was being scanned for future special effect uses). It is an apt metaphor for this documentary: the soliloquies offer lots of information but the portrait of Brando remains incomplete. And so it should, given that the actor’s private voice is at the center of the narrative. This is a memoir — not an exposé. Brando is hard enough on himself. Did he mean for the tapes to be heard eventually? Is this a form of performance? And what motivated his archiving all this material?

Drawing on scenes from Brando’s films as well as on-camera interviews and TV clips, Listen to Me Marlon moves briskly through Brando’s career, often providing insights into his best performances. His pent up anger was infused into Stanley Kowalski, guilt and warmth shaped Don Corleone, confessional panache was part of his turn in Last Tango in Paris. Brando is defensive about Apocalypse Now: “The script was stupid. I rewrote the whole thing. I told him how to shoot it.” He claims that director Francis Ford Coppola, in retribution, lied to the press about the actor coming to the set late, overweight, his lines unlearned. Brando was devastated: “Coppola is a card-carrying prick.”

His comments about studying under Stella Adler at the Actor’s Studio are illuminating: “Stella said ‘don’t be afraid of who you are. Act your soul, not the words. Everybody has a story; everybody is hiding something. We’re always acting. Acting is surviving.’” About his mother, whom he adored and respected, he admits: “My mother was an alcoholic. I loved the sweet smell of liquor on her breath.” His father was brutal. When Brando Sr. appears with the actor on TV, Brando cracks his killer smile, but his eyes tell another story.

Brando’s combination of beauty, sexuality, and pain was riveting. As it should, the movie avoids judgment on the tragic episodes in the actor’s life. Brando changed film acting forever, but he was an uncomfortable revolutionary. In the end he says, “I never asked for this life.” He hated being stared at in public, but confesses that the work had value. “Actors give the audience what they want, what they need.”

One of the resurrected paintings of Edith Lake Wilkinson.

Packed in a Trunk: The Lost Art of Edith Lake Wilkinson

This story of writer/producer/director Jane Anderson’s quest to find the truth about her great aunt received the Best Documentary award at the Festival. A part-time resident of Provincetown, Edith Lake Wilkinson demonstrated talent as a painter as an adolescent. She joined the Art Students’ League in 1888 at age of 20 and created some significant work. But in 1924 she was committed — under questionable circumstances — to the Sheppard Pratt Hospital in Baltimore, a sanitarium for the mentally ill. Most of the paintings were packed away, though Anderson grew up surrounded by the canvases that were kept on display. After a busy career in film and television, Anderson set aside two years and, along with her partner Tess and partner/filmmakers Michelle Boyaner and Barbara Green, set out to to find what just what happened to her great aunt. Her mission was not only to solve the mystery; she wanted to serve her great aunt’s legacy and mount an exhibition of her art in Provincetown. This is a movie with a stunning payoff that received a standing ovation.

I wont give away the end of a narrative that is both detective story and a lesson in art history. What moves the documentary along is the boundless energy of the charismatic Anderson. It turns out that her great aunt’s works are distinctive; the paintings transcend much of the traditional landscape and portrait work seen in Provincetown at the time. More remarkable are the synchronicities between Anderson and Wilkinson, who passed away in 1957. At one point Anderson even consults celebrity psychic Lisa Williams to find out more from The Great Beyond. What they discover is jaw-dropping. I asked Anderson about the spirit-consultation scene. She said that she is not a believer, but that Williams’ insights were plausible and added a lot to her understanding of who Edith Lake Wilkinson was. Several of the psychic’s visions were confirmed in the course of the director’s research. By firmly establishing Wilkinson’s status as a female artistic innovator, Anderson affirmed her own life choices. During the Q&A after the screening, a tearful Anderson was emphatic: “I am living the life that Edith could never have. I owe her this film.”

A scene from “Tangerine.”

The world of transsexual (and transitioning) prostitutes and hustlers is not one with which I am familiar. I am now. Director Sean Baker, working with Indie actor/producer Mark Duplass, did an extensive amount of research. Tangerine is set on Christmas Eve at a location where such underground activity is common: the intersection of Santa Monica and Highland in Los Angeles. There are also a number of scenes shot at a local Donut Time restaurant. The filmmakers cast Mya Taylor, a local African-American transgender woman, as Alexandra and her friend Kitana Kiki Rodriguez as Sin-Dee Rella. The story follows Sin-Dee and Alexandra as each goes about their trade. Sin-Dee, however, has one goal – to get her revenge on the white girl with whom her boyfriend Chester had an affair while Sin-Dee was serving a short prison sentence. A third story involves an Armenian cab driver, Ramzik, who picks up badly behaved fares and later leaves his family’s dinner to seek out a prostitute. The various stories converge.

Christmas Eve in LA doesn’t feel quite like a traditional Christmas, but then again nothing seems right or predictable as Sin-Dee and Alexandra walk the streets, jabbering and kvetching. The camera follows them everywhere. They never stop talking and the cab driver has his own bizarre agenda. The colors are garish and the action moves very fast. The composition of the frame is woozy; the two prostitutes explode off the screen. I asked producer Shih-Ching Tsou how the creators achieved the kinetic camera work and saturated colors. The answer, to my amazement, is that it was all shot on an iPhone 6 in just 5 days and edited with Final Cut Pro. This has since become quite a topic of conversation on blogs and in the press. The producer also said that the owners of the Donut Time restaurant haven’t seen the film yet.

A scene from “Nasty Baby.”

Nasty Baby

I was in the minority when I applauded at the end of this unconventional film. The storyline veers from one plot point to the next and then changes genres about 2/3 of the way through. Avoiding spoilers, the essential narrative is this: a mixed race gay couple in Brooklyn, Freddy (the film’s director Sebastián Silva) and Mo (Tunde Adebimpe from the band TV On the Radio), want a baby. Their best friend, Polly (Kristen Wiig), volunteers to be the surrogate mother. It turns out to be a messy and challenging task.

Freddy’s sperm is not quite up to the task, nor is Mo’s ability to perform. In a sub-plot, Richard (Mark Margolis, in a distinct change from his demented Tio Salamanca in Breaking Bad), is a kindly neighbor. He comes to the couples’ defense when they have problems with a slightly insane resident known only as “The Bishop” (Reg E. Cathey from House of Cards). That pesky neighbor has been rousing the couple every morning with noise from his unnecessary leaf blower. He harasses Polly for dealing with “fags.” While all this is going on, Freddy, a struggling artist, is creating a video-performance piece in anticipation of the baby. The work will be called “Nasty Baby,” and it includes adult performers doing babbling infant impressions. Nothing goes well for anybody. Eventually, the movie moves to another story entirely before reaching a darkly comic, open-ended conclusion.

Chilean director Sebastián Silva also wrote and directed the 2009 film The Maid, which was about a family servant who, after 27 years of service, seriously oversteps her bounds. In 2013, he was at the helm of Crystal Fairy & the Magical Cactus, which can best be described as a psychedelic comedy. In that film, two Americans (Michael Cera and Gaby Hoffmann) go on a quest in Chile for a special hallucinogenic cactus plant.The storyline is a send-up of New Age culture, but it is based on Silva’s own experiences taking mescaline in the desert and meeting a woman named Crystal Fairy. Inspired by a 20-page outline, the dialogue is largely improvised. Silva finished this film just prior to receiving funds for the film Magic Magic, which also starred Michael Cera.

I knew none of this when I saw Nasty Baby, but I had loved The Maid and Crystal Fairy. Silva’s political edge, improvisational style, unpredictable plots, and non-traditional characters are enchanting. He casts actors who ordinarily wouldn’t work together and pulls from them natural and brave performances. As in his other films, Nasty Baby‘s scenario is unpredictable and outrageous, but somehow it feels true. The film is a sly satire on parenthood, adult responsibility, gay acceptance, city neighborhoods, the pretentions of the art world, mental illness, and the fickle comedy of fate. Most commercial cinema has become predictable to the point of putrefaction. I love that now and again I see a film where I have no idea where I’m headed.

Tim Jackson is an assistant professor at the New England Institute of Art in the Digital Film and Video Department. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, many recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate and has also has worked helter skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed a trio of documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater, and Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups. His third documentary, When Things Go Wrong, about the Boston singer/songwriter Robin Lane, with whom he has worked for 30 years, has just been completed. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog.

A terrrific complement to my own piece on the P-Town Festival. A lovely description of the Brando movie. I wish I’d seen Packed in a Trunk. We both watched Nasty Baby and had different levels of liking it. Tim, making a positive case for the film, you didn’t dare talk in detail about the movie’s bizarre change in plot and tone and genre in the last quarter, suddenly — and without any motivation — becoming a Patricia Highsmith murder mystery.