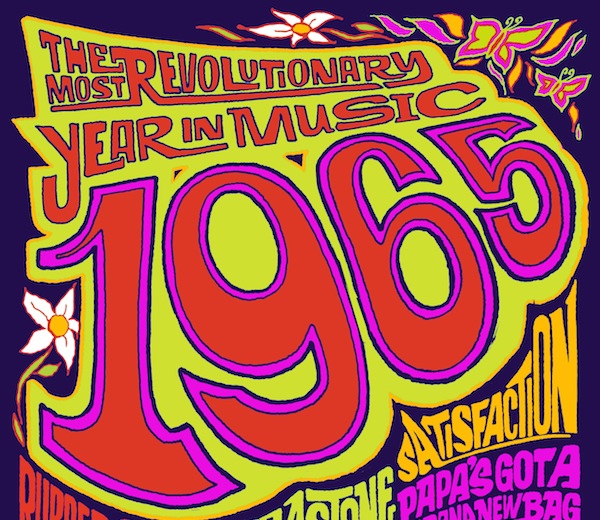

Music Interview: Andrew Grant Jackson on 1965, Music’s ‘Annus Mirabilis’

1965 was the year in which the leading artists in American and British popular music pushed themselves beyond making albums that mixed covers with subpar originals and strove to create their own classics.

By Blake Maddux

Andrew Grant Jackson’s latest book is 1965: The Most Revolutionary Year in Music (Thomas Dunne/St. Martin’s. 328 pp. $27.99), a project that encouraged him to simultaneously indulge in and to branch out a bit from his chronic case of Beatlemania.

1965 was the year in which the leading artists in American and British popular music pushed themselves beyond making albums that mixed covers with subpar originals and strove to create their own classics. The result was that all of these musicians influenced each other in a spirit not so much of competition as admiration.

Behind the scenes, songwriting teams in New York City (e.g., Carole King and Gerry Goffin at the Brill Building) and Detroit (Holland-Dozier-Holland at Motown) were composing the tunes that would define genres and a generation, while practically unknown teams of session musicians dubbed The Wrecking Crew and The Funk Brothers provided the instrumental accompaniment on the recordings.

By the end of this annus mirabilis, purveyors of rock, pop, folk-rock, soul, funk, jazz, and country had all made profound commercial and artistic statements.

In addition to maintaining an admirably thorough Beatles website, Andrew Grant Jackson – an Emerson college alum – has written two previous books about the Fab Four: Still the Greatest: The Essential Songs of The Beatles’ Solo Careers and Where’s Ringo?, a book of cartoons in which one must locate Liverpool’s best-known percussionist rather than the more famously elusive character.

Having worked as Jeff Bridges’s Development Associate at AsIs Productions and tried his hand at screenwriting, he now writes about music and culture and has contributed to sites like Slate and Rolling Stone and is the proud father of a five-year-old daughter.

Jackson spoke to The Arts Fuse by phone from his home in Los Angeles about the book in which he expertly and lovingly recreates a defining year in American political, social, and popular culture.

Arts Fuse: What took you from Detroit to Emerson College to Los Angeles?

Andrew Grant Jackson: I was a mass communications major [at Emerson]. My dad did car commercials, being from Detroit, so I always wanted to do film. And then I came out to L.A. and I was writing scripts. I did an indie film called The Discontents [2004] that was in festivals but didn’t sell. So I wrote scripts but I wasn’t having any luck. Kind of out of pure escapism I kind of got obsessed with…I’d always loved The Beatles, and I then I suddenly got obsessed with their solo music. The Internet came around and I could explore it all without shelling out thousands of dollars and stuff. So then I did a book on that and I just wanted to keep rolling after that book. It turned out that music criticism ended up being better for me than film, although I did a lot of film jobs and worked for a lot of entertainment companies.

Andrew Grant Jackson — He’s a music journalist because in his heart he would like to play but it didn’t work out that way. Photo courtesy of the author.

AF: Are you a musician, trained or otherwise?

Jackson: Well, I played drums in high school in a couple little bands but they never got out of the garage. Total, ultra-garage bands that never even played anywhere else. So that was the extent of it. I loved writing the lyrics, but I couldn’t really sing too well. I guess that’s why I’m a music journalist, right? Cause in my heart I’d like to play but it didn’t work out that way, though. I think trying learn those things helped me appreciate it more.

AF: In the book 1965, you do a fine job of alternating between the revolutionary musical and political scenes. Are you a history buff?

Jackson: Yeah, that was my minor in college. And I think my name was coincidental. My first name was one grandfather’s middle name and then my middle name was my other grandfather’s first name. Subliminally, that probably made me a little more interested than maybe the regular student in history. So I was always reading about that stuff. Although the more I read about Andrew Jackson, I get a little unnerved because of his policies toward the Native Americans and all that.

AF: Did growing up in Detroit make you a fan of Motown?

Jackson: Definitely. I think that more than anywhere else in the country, that music is in heavy rotation everywhere. So it seeps into your subconscious. It’s still on oldies stations everywhere, but probably in Detroit 50 times more than anywhere else. I was a little kid in the ’70s, but Detroit had a slow, decades-long kind of decline at least in terms of the city itself. But my dad lived downtown in the ’70s, so it still had an amazing feel to it even though it was getting more dangerous as every year went by. That was one of the things I loved about writing the book: getting to describe Motown a little bit.

AF: Did you discover music on your own or did your parents have it around the house?

Jackson: My dad, whenever we were driving anywhere, [would play The Beatles’] Abbey Road and Sgt. Pepper and High Tides and Green Grass, which was a Rolling Stones compilation. And they had Simon & Garfunkel’s Greatest Hits. Around 12 or so I started going off further into it on my own. Getting more into all of the Beatles albums and everything. But it was definitely through my parents originally.

AF: Is 1965 your favorite year for music?

Jackson: For me if I only had ’65 to listen to but I could never listen to the other years…whatever year you’re forced to listen to, you’ll kind of yearn for the other ones, so I think it’s great to be able to switch ‘em around, because I love Blonde On Blonde [Bob Dylan, 1966] and Revolver [The Beatles, 1966] and Beggars Banquet [The Rolling Stones] from ‘68 and all that stuff. Personally, I guess, I always loved oldies from even like Buddy Holly and Elvis and then I loved all the stuff after ’65, which got more heavy and psychedelic. For me ’65 was like the perfect combination year of both. It’s still kind of had that old-fashioned kind of feel to an extent, but then you hear all the new crazy trippy stuff kind of emerging from it simultaneously. That’s why I got the most kick out of ’65. I think it was the most transformative year.

AF: Who were some of the lesser-known or underappreciated contributors to the ’65 sound?

Jackson: At lot of people know them, and I think they are getting more attention all the time, but The Staple Singers did this tune “Freedom Highway” that they recorded in early April, right after the march from Selma to Montgomery. I think it’s just a really rousing song. I think the album is being reissued this year because of the 50th anniversary. I fascinated by the fact that Mavis Staples, the lead singer, and Dylan were having an affair throughout the decade. When he wrote “Like a Rolling Stone,” on the hotel stationary or something, he wrote her name on the page.

And also the gospel singer Mahalia Jackson is due for a bit of a reappraisal. He’s definitely not underappreciated, but I liked going off from the rock thing and talking about Waylon Jennings. It was interesting getting into him and early Bob Marley, and ska and stuff like that.

AF: Was the titular year the best year of any particular musician’s career?

Jackson: I don’t know his later work enough to say that it was the pinnacle, but it was definitely [a great year] for Gene Clark of The Byrds. I think if you took all of the Gene Clark songs from that year you could probably put together one amazing Gene Clark Byrds album.

The Beach Boys, if you took just the best stuff and made an album, personally I might like that even better than Pet Sounds [1966], because it’s a little more upbeat. I love Pet Sounds but it’s somewhat melancholy and mellow, so you’ve got to be in that mood.

The Rolling Stones, it wasn’t their best year. Their albums were still primarily covers, but they had so many great originals that year that if you pulled all those into one coherent album, that would have been – I don’t know, I’m going a bit out on a limb – but that might have equaled [Bob Dylan’s] Highway 61 Revisited and [The Beatles’] Rubber Soul.

AF: Have any other years or eras of the past 50 years given 1965 a run for its money?

Jackson: The late 70s period, when you had disco, punk, and hip-hop all kind of exploding out of New York, that was probably one of the most revolutionary periods after the ’60s. Then in the early ’90s you had alternative, Nirvana and all that, and gangsta rap both booming. So that was another big time, too.

AF: Before closing, I would like to ask you something related to your book Still the Greatest: Are there any Beatles solo albums that are better than any LP released by the band?

The album Yellow Submarine [1969] by The Beatles has got only four new songs and then it has all instrumentals on the second side. If you include that one, then there are a lot of [solo] albums that that you can say are better. The classic solo albums are probably [John Lennon’s] Plastic Ono Band and Imagine, [Wings’] Band on the Run, [Paul McCartney’s] Ram is getting a lot more respect lately, [and George Harrison’s] All Things Must Pass. Being an oldies fan, I love the early Beatles, too. But those who like the later Beatles albums might like the solo albums more than the early Beatles albums. Personally I’d have to say the Beatles albums are still going to be a little bit better than any of the solo albums.

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist who also contributes to The Somerville Times, DigBoston, Lynn Happens, and various Wicked Local publications on the North Shore. In 2013, he received a Master of Liberal Arts from Harvard Extension School, which awarded him the Dean’s Prize for Outstanding Thesis in Journalism. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife in Salem, Massachusetts.

Tagged: 1965: The Most Revolutionary Year in Music, Andrew Grant Jackson, Beatlemania