Arts Reconsideration: The 1971 Project — Celebrating a Great Year in Music (September Entry)

Looking back after 50 years, the great albums in this month’s entry for the 1971 Project all seem frozen in time as immortal classics. But in their own day, these albums each had their eye on history and legacy in diverse ways. The Who, Bob Dylan, and the Beach Boys were all aware of their fans’ expectations, and each created brave new music to recast their images and free themselves to explore new roads of creativity. Classical composer George Rochberg released the traditional string quartet from its chains to the past, writing a musical manifesto for what would become a new postmodern age. Finally, a new band from Texas with the oddball name ZZ Top had the temerity to title their first album ZZ Top’s First Album, which now sounds conveniently factual, but at the time was a confident declaration that there would be more to come.

For those who missed them, here are the 1971 music entries for February, March, April, May, June, July, and August.

What are your impressions and memories of these records, and what are your favorite masterpieces from 1971? Let us know in the comments.

— Allen Michie

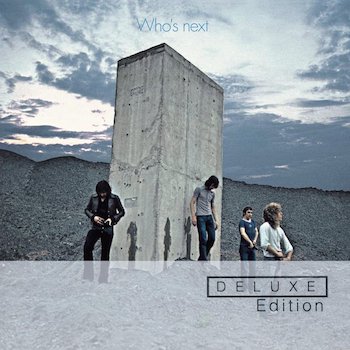

The Who, Who’s Next (Decca)

So, the GRROAT? Greatest rock record of all time? Why not? After all, Live at Leeds (1970), its precursor, was “the best live rock album ever made.”

So, the GRROAT? Greatest rock record of all time? Why not? After all, Live at Leeds (1970), its precursor, was “the best live rock album ever made.”

Pete Townshend had intended to write a follow-up rock opera to Tommy, called Lifehouse, but that project collapsed and Who’s Next emerged, with a few Lifehouse leftovers.

Just as well: no godawful corny storyline or meandering bubblegum teen narrative connective tissue. Here was rock, with no roll — no rockabilly swing, no Delta-blues shuffle, no doo-wop. The power chords of “Won’t Get Fooled Again” (which would eventually ring, it seemed, through ubiquitous TV crime dramas and car commercials), the stentorian vocals, and the pummeling, foursquare but fluid drums: it was all glorious bombast. Here’s one epic anthem after another, one singable hit after another, if not in whole then in parts (“Gettin’ in tune to the straight and narrow”; “I don’t care about pollution/I’m an air-conditioned gypsy”) and anti-slogans (“They’re all wasted!”).

And the music. Chord progressions that never wear, while at the same time avoiding proggy pretension. A virtuoso rhythm section that was as flexible as it was hard and fast, the beats seeming to turn on themselves and go backwards. (A friend of mine asked of Live at Leeds, “Since when does the guitarist get his ideas from the drummer?”) And those tunes — at least two hit power ballads, “Love Ain’t for Keeping,” and the dystopian diptych “Behind Blue Eyes” (“And if I swallow anything evil/put your finger down my throat”), and singable melodies everywhere.

Instead of the opera, we got a dystopian cyberpunk vision, right there in the slag heap wasteland album cover and its men’s room joke (pissing on Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 monolith, no less). From the very beginning, with the frozen mechanistic hailstorm of those predigital sequenced synths on “Baba O’Riley,” to the finale of “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” the music seemed to emerge in elemental bytes from that wasteland, and the question was “What is this stuff?” Guru Meher Baba meets minimalist godfather Terry Riley? How many other rock albums leave indelible slogans to go along with all those indelible tunes? “Meet the new boss/Same as the old boss” is now as much a boomer op-ed cliché as the musical cliché of those car commercial power chords. But that’s only because they’re as undeniable as “Don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.” And if you doubt it, listen again, in context, on Who’s Next. Townshend has recorded two rock operas, but this is his epic masterpiece.

-Jon Garelick

Bob Dylan, Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits, Vol. 2 (Columbia)

An artist as capacious as Bob Dylan was an awkward fit for the music industry contrivance known as the Greatest Hits album. Dylan’s singles were only sporadically his major works. Thankfully, Dylan compositions recorded by others were intrinsic to the concept in both Greatest Hits 1 and 2. This latter volume, from November 1971, wisely included songs from as far back as 1963.

An artist as capacious as Bob Dylan was an awkward fit for the music industry contrivance known as the Greatest Hits album. Dylan’s singles were only sporadically his major works. Thankfully, Dylan compositions recorded by others were intrinsic to the concept in both Greatest Hits 1 and 2. This latter volume, from November 1971, wisely included songs from as far back as 1963.

Yet it is still a strange bird. There was only one real reason ardent Dylan lovers like myself anticipated the release of Vol. 2 as a major event: there were a handful of new songs promised. A cup of water in the desert seems a miracle.

By 1971 there’d been no regular concerts in five years. And the albums since 1968’s transcendent John Wesley Harding were minor affairs, some crooned in a manner more Bing than Woody. (The deliberately underwhelming Self Portrait was Bob’s perverse attempt to stave off Dylan-idolatry.) Beneath the changes in voice and genre, it seemed his fountain of inspiration had receded to a trickle. The very first words that led off the double album — from his latest single (and nonhit) “Watching The River Flow” — bluntly confronted this very issue: “What’s the matter with me/I don’t have much to say.”

Placed next to “Watching,” 1963’s “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright” now seems like a precious relic from an entirely other lifetime. Attitudinally, both songs take the stance of purposeful retreat but, in the old gem, irony abounds. The album’s most felicitous choice of early Dylan was the previously unreleased “Tomorrow Is A Long Time,” a nakedly tender love ballad covered by both Elvis Presley and Judy Collins.

Among the 21 selections are some of the most potent, many-layered songs of the 20th century. Yet when you hear “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” followed by the cliché-ridden “If Not For You,” it causes aesthetic whiplash. The inclusion of the latter song was no doubt a product of industry thinking: there “had” to be a song from the slight New Morning LP, and this one was recorded by both George Harrison and Olivia-Newton John. But give Bobby Dylan credit even here: After recently listening to this catchy song just once, I sang and hummed it to myself all day and night!

On the three songs recorded with guitarist Happy Traum expressly for this project, the best news for fans was that he’d dropped the country croon for his old rough-and-ready nasal plea: very folkie, and casually credible. There are playful new lyrics and a fine, frisky vocal on “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere.” “I Shall Be Released” can’t hold a candle to The Band’s version, but it is heartfelt. The stripped-down acoustic approach suggests a man who wants to be himself — not the godhead DYLAN. The last words on “Down In The Flood” — the last words on the whole double album — seemed to be a direct message to his fans: “You’re gonna have to find yourself another best friend somehow.”

–Daniel Gewertz

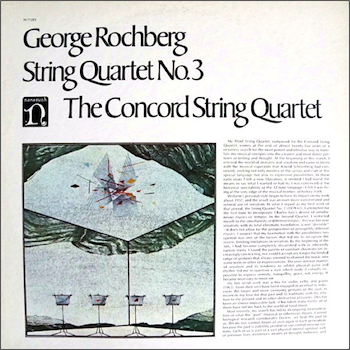

George Rochberg, String Quartet No. 3 (Nonesuch)

As I said in regard to a famous series of Bach recordings, 1971 was a watershed year for classical music, as I clearly recall. (I was 22.)

As I said in regard to a famous series of Bach recordings, 1971 was a watershed year for classical music, as I clearly recall. (I was 22.)

1971 was the year that George Rochberg completed his String Quartet No. 3. Its first performance (in 1972) got lots of attention in the press. Negative, mostly. Rochberg was treated as a kind of traitor, his music now, in Andrew Porter’s word, “irrelevant” to the modern age. I didn’t catch up with the Third Quartet until the Nonesuch recording came out in 1973, when a fellow grad student (a composer) insisted that I come to his apartment to listen together to this brave new work. I was astounded. (It was released in Quadraphonic sound — remember that? — but we heard it through two speakers.)

There, nestled in the middle of a piece otherwise written in the usual rebarbative style of high modernism, was a slow movement (theme and variations) that sounded for all the world like a previously unknown movement from a late Beethoven quartet amped up with some harmonic coloration from Mahler. For many of us classical-music lovers, “the Rochberg Third” announced that postmodernism had arrived; obeisance to the cult of Schoenberg, Babbitt, and Boulez was no longer required; and new music could now be … all kinds of different things. (In retrospect, a more accessible strand of modernism had already been available for emulation, in works of Sibelius, Poulenc, Vaughan Williams, Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Bartók, Britten, Copland, Weill, Blitzstein, Bernstein…) The liberatory ’60s, in short, finally reached the world of classical music in 1971, with effects that are still with us.

—Ralph P. Locke

ZZ Top, ZZ Top’s First Album (Warner Bros.)

That little ol’ band from Texas was certainly making a statement when it titled its debut record ZZ Top’s First Album, confident that there would be more to come.

That little ol’ band from Texas was certainly making a statement when it titled its debut record ZZ Top’s First Album, confident that there would be more to come.

And true to its word, ZZ Top released a string of very successful albums, hitting a couple of commercial peaks — first in the ’70s with such FM rock radio staples as “La Grange” and “Tush,” and then again in the ’80s with MTV-powered hits “Gimme All Your Lovin’,” “Sharp Dressed Man,” and others — that have sustained a career that remains vibrant to this day. (Although the future does seem a bit uncertain for ZZ Top, given that founding bass player Dusty Hill died on July 28.)

Released in January of 1971, ZZ Top’s First Album, while not yielding any big hits that became signature tunes, can be viewed as a blueprint that the trio of guitarist Billy Gibbons, drummer Frank Beard (though credited as Rube Beard on this record), and Hill continuously used to great effect with minimal variation.

The blues serve as ZZ Top’s anchor, and Gibbons is a masterful guitarist within the genre, preferring a hip, sinewy, groove-laden style over any sort of flashy excess (which belies the approach that the band took with its stage shows that grew to rodeo-sized proportions at the height of its fame).

It’s not hard to peel back the synthy veneer of the ’80s hits and find the heart of First Album. Beard and Hill hold down a driving, insistent unflappable beat. This was no Yes. Gibbons deploys searing riffs and licks, playing with an economy that stays closer to the blues tradition compared to bands inspired by Cream, whose approach was to stretch out the blues into lengthy psychedelic jams. And he establishes a badass vocal style that somehow balls together a drawl, a slur, and a growl. The effect is, for lack of a better term, nocturnal.

Then there’s the sex.

ZZ Top’s catalog is stuffed with carnal innuendo and euphemisms, and it all started with “(Somebody Else Been) Shaking Your Tree,” track one on side one of First Album. “Brown Sugar” is not a song about baking. And the mischief continues through “Bedroom Thang,” “Just Got Back from Baby’s,” and “Backdoor Love Affair.”

ZZ Top’s weirdo humor bubbles up on “Squank,” and the group’s knack for unfolding a twisted tale is on display with the Hill-sung “Goin’ Down To Mexico” and Gibbons’s murderous “Neighbor, Neighbor.”

ZZ Top worked and reworked these elements into what you’d call the Classic Top of “Tube Snake Boogie,” “Cheap Sunglasses” and “Precious and Grace.”

Gibbons and Beard have continued to perform with longtime guitar tech Elwood Francis playing bass. But it’s a shame we’ve lost the opportunity to hear Hill dig into First Album, should ZZ Top decide to pull out any of its tracks in honor of the record’s 50th anniversary. To once again serve up what was described on the back cover of their debut as “abstract blues … from friends.”

–Scott McLennan

The Beach Boys, Surf’s Up (Warner Bros.)

The book on the Beach Boys’ recorded output post 1966’s Pet Sounds, and particularly its albums during the ’70s, is that mastermind Brian Wilson was out of commission. He had been bloodied and bowed after pulling the plug on the legendary Smile album, which was supposed to vie with Sgt. Pepper’s (which the Beatles were working on simultaneously). This caused the rest of the band to flounder miserably until the 1974 compilation of early surf-era hits, Endless Summer, saved their fortunes. It’s long past time to toss this book out the window, for while their studio albums in the wake of Pet Sounds didn’t do as well as they had before, the early ’70s in particular were a creatively fertile time for the Beach Boys, Brian included.

The book on the Beach Boys’ recorded output post 1966’s Pet Sounds, and particularly its albums during the ’70s, is that mastermind Brian Wilson was out of commission. He had been bloodied and bowed after pulling the plug on the legendary Smile album, which was supposed to vie with Sgt. Pepper’s (which the Beatles were working on simultaneously). This caused the rest of the band to flounder miserably until the 1974 compilation of early surf-era hits, Endless Summer, saved their fortunes. It’s long past time to toss this book out the window, for while their studio albums in the wake of Pet Sounds didn’t do as well as they had before, the early ’70s in particular were a creatively fertile time for the Beach Boys, Brian included.

Surf’s Up, the title track of which was to have been a centerpiece of Smile, was their second album for Warner Brothers, an attempt to update their image and sound while harking back to past glory. (It is also one of the two albums bookending the just-released five-CD boxed set Feel Flows, reviewed by me for Arts Fuse) From the album’s cover — a Native American on horseback in dark blues and greens, an image at odds in every way with the sunny album title — to the moody, mostly mid-tempo music within, the message was clear. This is not your older sibling’s Beach Boys.

Speaking of siblings, the band was always fortunate to have three brothers: Brian, Carl, and Dennis Wilson. While Brian wrote all their best material, his brothers stepped up admirably after he drew back following Smile’s dissolution. Dennis began writing great songs in 1968 and was arguably the star of 1970’s Sunflower. On Surf’s Up, Carl came to the fore with two stellar compositions: “Long Promised Road,” featuring a blistering guitar solo, and “Feel Flows,” a trippy number that Cameron Crowe selected to play over the end credits for the film Almost Famous.

In addition, the album features Bruce Johnston’s best-ever contribution, “Disney Girls” — later covered by Cass Elliot, Art Garfunkel, and the Captain and Tennille (“Captain” Daryl Dragon played in the Beach Boys’ touring band at the time and was a frequent songwriting partner with Dennis Wilson). Rhythm guitarist Al Jardine, who tours with Brian to this day, scored with an earnest folk ballad called “Lookin’ at Tomorrow.” “Student Demonstration Time,” Mike Love’s lyric rewrite of “Riot in Cell Block #9,” comments on the Vietnam-era protests on college campuses.

But as ever, it was Brian who produced the album’s highlights. “A Day in the Life of a Tree” and “’Til I Die” are autobiographical songs that show the depths of Brian’s encroaching mental illness, which included depression. “’Til I Die” in particular, with its bald lyrics of sheer hopelessness, would be a difficult listen if not for its beautiful arrangement and vocals. Still, the jewel of the collection is the last song, “Surf’s Up,” salvaged from the Smile scrap heap. This, to me, is Brian’s greatest composition, and no less an authority than Leonard Bernstein praised the work on CBS television. With lyrics by Van Dyke Parks that are as moving as they are abstract, “Surf’s Up” features a newly recorded lead vocal by Carl in the first part of the song, followed by Brian’s original 1967 vocal for the second part. The song ends with an elegant and ultimately triumphant weaving of disparate vocal lines sung by the band that is simply astounding, the equal at least of anything on Pet Sounds.

— Jason M. Rubin

Tagged: Allen Michie, Bob-Dylan, Daniel Gewertz, George Rochberg, Ralph Locke, Surf's Up, The Beach Boys, The Who, Who's Next

I just can’t get past that album cover for “Surf’s Up.” I don’t think of existentialist irony when I think of The Beach Boys.