Jazz CD Reviews: John Scofield’s “Überjam Deux” and Dave Holland’s “Prism”

Dave Holland’s Prism tells stories, several of which are very effective. Scofield’s, like his earlier Überjam releases, extends the jam-band esthetic into jazz without completely giving in to it. And neither of them would be as they are without the great looming shadow of Miles Davis.

Überjam Deux by John Scofield (with Avi Bortnick, John Medeski, Andy Hess, Adam Deitch, Louis Cato). Emarcy CD, 2013.

Prism by Dave Holland, Kevin Eubanks, Craig Taborn, and Eric Harland. Dare2 CD, 2013.

By Steve Elman

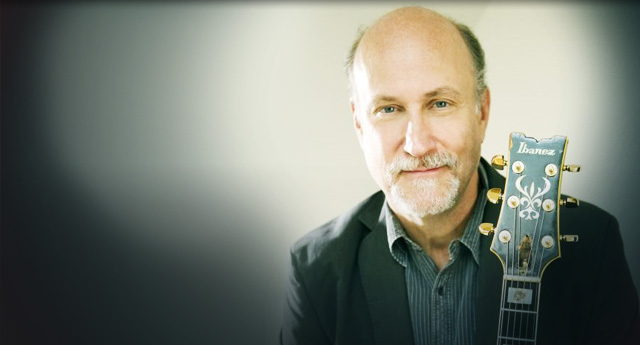

Twenty-two years after Miles Davis’s death, 28 years after John Scofield played with Miles, 43 years after Dave Holland played with Miles, we have new CDs by Scofield and Holland, and I still can’t help thinking about Miles.

Holland’s new band Prism, featuring guitarist Kevin Eubanks and keyboardist Craig Taborn, is solidly connected to the music Miles Davis was making in the late 1960s and early 1970s—the period that spawned Herbie Hancock’s space music band, Weather Report, Circle, the Mahavishnu Orchestra, the Tony Williams Lifetime, and many other less-successful projects that would have been very different or not at all if Miles hadn’t inspired the musicians who went out on their own to make them.

Scofield’s new CD reunites the members of his Überjam band, featuring guitarist/electronics whiz Avi Bortnick, who were last heard on Überjam (2002) and Up All Night (2003). Even though this group’s aesthetic draws a lot from traditions that are removed from jazz, when Scofield solos he brings back memories of his stint with Miles from 1983–1985, arguably Miles’s most jam-band oriented period.

Maybe the place to start is with a short and oversimplified digression on the difference between forward motion and stasis in music.

Jazz is, for the most part, a form that uses “development” as it’s been understood in Western music from the Renaissance onward—the idea that a musical performance is supposed to take the listener from one place to another, much in the way that a drama or a story does. A great jazz solo has long been described as one that “tells a story,” and the phrase can be applied equally validly to a good blowing tune or a successful jazz composition, especially when either is enriched by a centerpiece of good improvisation. Even though most of the basic forms on which jazz performances are built—blues, popular songs, original compositions with chorus structures, even free-form pieces built on pre-composed heads—are circular, jazz interpretations make them into spirals. The solos on these tunes aren’t simply supposed to replicate the emotional or musical material of the composition but rather to expand them, to take them to new places, to invest them with new meaning. And, to come back to the starting point, one of the greatest story-tellers of all was Miles Davis.

The marathon improvisations on modal structures that possessed John Coltrane and his acolytes in the 1960s drew from the story-telling tradition, but they stretched it so far that it approached the stasis esthetic, consciously building on Indian, African, and other non-Western idioms.

India, Africa, China, Japan, and the Middle East (just to name a few) have centuries of music that prizes stability more than forward motion—the essential goal is not to take the listener from one place to another but to lock him or her into a groove, a state of mind, timelessness, ecstasy. Within the past 70 years, Western musicians have drawn on and transformed this idea, from classical (Terry Riley, Steve Reich, etc.) to neo-ethnic (drum ensembles, gamelan orchestras, etc.) It took on the boldest of Western clothes when James Brown innovated pure uncut Funk, music that was supposed to grab you instantly with a beat, get you moving, and never let you go.

Miles drew on JB and his 1960s spawn, like Sly and the Family Stone, in the early 1970s as he moved his group away from music that developed in traditional ways and opted for longer and longer jams that slipped from one tune to another, noodled on for many minutes of groove, and then either stopped suddenly or petered out. What many rock listeners perceive as the distinctive subgenre of jam-band emerged in the wake of the modal movement in jazz—the long formless jam was first embraced by the Byrds, then The Grateful Dead, then Cream. Their group improvisations had some of the feel of jazz, but the performances became a transcendent wash of sound—crescendos and climaxes were incidental to overall effect. On that path a thousand flowers subsequently bloomed—Little Feat after Lowell George, Phish, Gov’t Mule, and all the rest.

The two CDs in hand are new examples of these two ancient esthetics. Dave Holland’s Prism tells stories, several of which are very effective. Scofield’s, like his earlier Überjam releases, extends the jam-band esthetic into jazz without completely giving in to it. And neither of them would be as they are without the great looming shadow of Miles Davis.

For about 15 years, Holland has led small groups that drew on and extended the traditions of small-group jazz typified by the iconic Blue Note groups of 1950s and 1960s—stellar soloists, original compositions with unusual structures and/or time signatures, plenty of solo space and compositional opportunity for all the members of the group, and, for want of a better term, an “acoustic” framework—a sound that avoided the amplification, distortion, and sound manipulation that distinguishes electric music. Holland was a charismatic leader, giving his groups a solid core—his remarkably rich bass sound—and a basic book of his own beautifully-crafted tunes, many of which showed the influence of George Russell’s Lydian Chromatic Concept. Occasional Latin tinges and periodic excursions into funk rounded out the picture and made these groups among the most satisfying of the new century.

The new group, Prism, is a departure, although Holland has pointedly said that he does not want it thought of as an “electric band.” This is correct—Prism is no more an electric band than is Dave Douglas’s quintet with Uri Caine. However, it dispenses with the brass, reeds, and vibraphone, which were integral to the sound of Holland’s earlier groups, and gives prominence to electric guitar and occasional electric piano.

The presence of guitarist Kevin Eubanks, who gained wide notice as leader of the Tonight Show band, might suggest that this group shades towards smooth jazz, but Eubanks fans will be in for a surprise. His fondness for Jimi Hendrix takes the lead role here, and he uses more distortion and fuzz on this CD than he has on any of his own releases as a leader. His own tune, “The Watcher,” leads the CD, and he sounds as aggressive as Vernon Reid on it. Elsewhere, he pulls back, using some Leslie effects and damped-string picking to make his solos pungent. As always, he’s a fine craftsman with cogent things to say.

I was unfamiliar with keyboardist Craig Taborn’s work before hearing this CD, and shame on me. He’s adept on acoustic and electric keyboards, a strong soloist, and a very interesting composer. His “Spirals” has a long line in odd rhythm, with splashes of free improv between the more formal solos.

Drummer Eric Harland served several years with SF Jazz Collective and sharpened his compositional chops there. His gospel-flavored “Choir” is easily the most appealing thing on the Prism CD, with some nice stop-time effects in the head.

So why don’t all these elements add up to a more satisfying CD? One problem is the dry acoustic, which makes the music feel tight and constrained; a little more presence on the guitar would have helped, I think. (Holland himself produced this release, so he has to take some responsibility for this.) Second, the sonic materials are by their very nature limited in timbre—the addition of Sasha Sipiagin’s trumpet or Steve Nelson’s vibes would have refreshed the familiar guitar-keyboard combination and incidentally would have provided a link to Holland’s earlier band. Third, I have the sense that Prism is still feeling its way toward a collective identity. Holland has said he prefers not to record until he feels the music is right, and this CD may have been a bit premature. In this case, everything is rehearsed and executed beautifully, but there isn’t a sense that the players are in real conversation with each other. Considering the cohesive nature of his previous groups, that’s an understandable and maybe an unrealistic expectation. Maybe the next Prism CD will have more of what I’m missing here.

John Scofield’s Überjam Deux is less conventional as a jazz CD, but it’s more appealing as group music. The dynamic of this well-seasoned band depends greatly on the interaction of Scofield and fellow guitarist Avi Bortnick, and the two have forged a very interesting partnership. Bortnick does not solo at all on the CD; in fact, no one takes a traditional solo except Scofield. But Bortnick’s contribution is fascinating. He provides rhythm guitar figures and “atmospheres” for the tunes from sampled and pre-recorded sounds, which he mixes live into performance using pedal controls. In effect, he sets up a framework for Scofield’s melody lines, and “produces” the actual performance as it goes along. Keyboardist John Medeski is present on five tracks, but his contributions are more in the nature of additional atmosphere than in any out-front role.

This is the format for most of the CD, but there’s more variety to Überjam Deux than there was in either of the two previous Überjam releases (probably reflecting the diversity of Scofield’s many loves in music). In addition to the tracks with a pure-jam feel, like the very strong “Snake Dance” and “Endless Summer,” there’s the self-explanatory “Al Green Song,” “Curtis Knew” (with a hint of Curtis Mayfield’s “Get on Up”), a Ray Charles-style modified blues called “Scotown,” a reggae track called “Dub Dub,” and a cover of Ronnie Dyson’s “Just Don’t Want to Be Lonely.”

No complaints about the rhythm section—bassist Andy Hess and drummer Adam Deitch are veterans of the earlier Überjam band, though Deitch is replaced ably by Louis Cato on three tracks, and Tony Mason is driving the drums in their current tour.

All of these elements give the CD solid foundation and great surface appeal, and Scofield’s “aw-shucks-I-just-play-guitar” persona might lead one to think that that’s all he’s striving for. But John is actually a much wilier musician than his interviews sometimes indicate, and each of his solos on this CD elevates it to a place that is more creative than its context. Scofield has one of the greatest “story-telling” gifts in music. The first notes of his solos almost always seize your interest, and he brings you along from idea to idea in the spirit of (but far from the manner of) Jim Hall, for whom he has often expressed admiration. For me, those solos are what make Überjam Deux worthwhile. The jam-band-feel is agreeable and fun; Scofield brings it to a higher plane.

Prism and Überjam are both on tour this year. Prism opens in Monterey, CA on September 21, mostly spending time on the west coast before going to Europe in October, including stops in Vienna, Frankfurt, Amsterdam, Oslo, and London They return to the US for a show at Birdland in New York on November 26, which is as close as they will get to New England, at least in so far as dates that have been announced.

The first phase of Überjam’s current road trip concluded on August 4 in Salt Lake City. They resume touring on September 1 in Detroit with a number of US dates (including Chicago, DC, NYC, Seattle, and Cambridge, at the Regattabar, on September 11 and 12). After that, it’s a world-wide jaunt through the end of November—Shanghai, Tokyo, Berlin, Vienna, Amsterdam, Istanbul, etc. etc.

Lucky Angelenos will have the chance to see both bands on the same bill October 5 at UCLA’s Royce Hall.

Tagged: Adam Deitch, Andy Hess, Avi Bortnick, Craig Taborn, Dave Holland, Eric Harland, John Medeski, John Scofield, Kevin Eubanks, Louis Cato, Prism