Poetry Review: Jane Shore’s “That Said” — Early and Late

By Jim Kates

If the poems in That Said: New and Selected Poems had been ordered differently, the volume would have made more of its virtues.

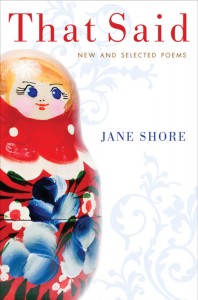

That Said: New and Selected Poems by Jane Shore. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 288 pages, $22.

The first professional book review I ever wrote was of Jane Shore’s 1977 debut Eye Level, and I singled out her verse as that of exploring the art of the eye-witness, of seeing. I wrote then, “There are those who will find [her] poetry too confined, too limited to the actual in its vision, who will feel restless with ‘such delicate maneuvering.’ But we can rejoice in being dissatisfied with a first book of this achievement and promise. Eye Level rewards a careful look, the careful look of a good witness who will see what can be seen and enter it as evidence of things unseen.”

Thirty-five years and a handful of books later, the first new poem of That Said, a collection of her new and selected poems that stretches back to her beginning as a poet, ends with the line, “I was the only one on earth who saw it fall.” (“Willow”) The poet is still looking at things at eye-level. What she was seeing in 1977, she still sees today. The jacket of the new book carries an image from probably the best known poem of her second book (The Minute Hand, 1987). Like “The Russian Doll” of that poem, her own work contains itself, reproduces itself, but always “yet to discover that self, / always hidden, who grows and shrinks, / who multiples and divides.”

In one sense, then, That Said comes as a disappointment: the title is all too accurate. The life that inspires these poems seems not to have moved very far in 35 years. We miss the height and depth that resonates in Shore’s earliest work. Eye Level proffers the wonderful “Fortunes Pantoum.”

You have a fear of visiting high places

Grasp at the shadow and lose the substance

Your misunderstanding will be cleared up in time

Sometimes you worry too much about death

By Music Minus One (1996) Shore settles into writing vignettes, sometime poignant, sometimes plodding, about family and growing up Jewish. The recurrent imagery and subject of dolls in her life is strong, right up through the compelling “Trouble Dolls” of her 2008 book, Yes-or-No Answer:

Single file, they descend

the mineshaft of my unconscious,

with only a pickax and hardhat

beam to light their path.

Gratuitous details (why does it matter that someone is wearing Marimekko in “Pickwick”?) weaken the narrative and the verse. All too many of the poems feel pointless, afflicted with the kind of rambling self-absorption that reeks of poetry workshops: “Write about . . .” For example, among the newest poems is “Fortune Cookies,” a pedestrian, short story of a narrative, somewhat weary in style:

We divided up the bill, and split.

A few left their fortunes behind.

The rest slipped those scraps of hope or doom

into pockets and pocketbooks to digest later.

The difference between this and the “Fortunes Pantoum” illustrates Richard Wilbur’s wise dictum that the genie gets his force by being confined in the bottle. The more Shore allows herself to be restricted by seemingly external constraints of one kind or another, the more powerful her verse becomes, from “Fortunes Pantoum” through her exploration in her more recent work of the ghazal in “Mirror/Mirror.”

Which Jane are you? I asked my mirror.

My mirror answered, Ask another mirror.

So what are we to do—admire the lifelong consistency of voice and vision, or lament the lack of growth and epiphany?

If That Said had been ordered differently the volume would have made more of its virtues. Because the new poems come first, Shore’s strengths become muddled. The more recent poems should be read as building on the visions of the older work, filling in the blanks, elaborating, just as The Midrashim heaps comments on earlier Talmudic texts. (Only after writing this did I notice that Stanley Plumly’s blurb also invokes the Talmud.)

Yet, after all, That Said fits neatly into my own notion that poems should be read individually, not as part of a scheme, even in a retrospective collection. Like people, most will leave us cold, a few here and there will catch our interest, and a rarer few will become inseparable parts of of our lives. So it happens to me with Shore’s poetry. That said, I guess I’m not so disappointed after all with this collection. And let it also be said, too, that the poet’s not done yet.

Jim Kates is a poet, feature journalist and reviewer, literary translator and the president and co-director of Zephyr Press, a non-profit press that focuses on contemporary works in translation from Russia, Eastern Europe, and Asia. His latest book is Muddy River (Carcanet), a translation of verse by Russian existentialist Sergey Stratanovsky. His translation of Mikhail Yeryomin: Selected Poems 1957-2009 (White Pine Press) won the second Cliff Becker Prize in Translation.