Opera Album Review: Gluck’s Final Opera Finally Steps into the Spotlight via a Superb New Recording

By Ralph P Locke

Rejected in Gluck’s time because it lacked dramatic thrust, today Écho and Narcissus proves to be a candy-box of delights.

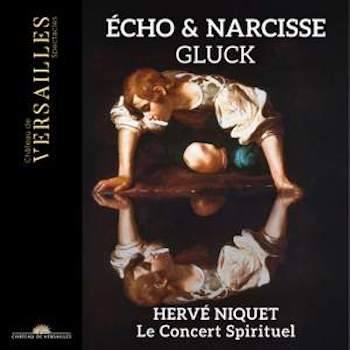

Écho and Narcissus, Christoph Willibald von Gluck

Adriana González (Écho), Myriam Leblanc (Amour), Cécile Achille (Eglé) Adèle Carlier (Aglaé), Cyrille Dubois (Narcisse), Sahy Ratia (Cynire).

Le Concert Spirituel, cond. Hervé Niquet.

Versailles Spectacles [2 CDs] 102 minutes.

To purchase or hear any track, click here.

Écho et Narcisse, the last opera of the great eighteenth-century composer Christoph Willibald von Gluck, was first performed at the Paris Opéra in 1779, where it failed in its first staging as well as in two subsequent attempts at remounting it during the composer’s lifetime. Perhaps because of this, the work has only been recorded once before: in 1987, by René Jacobs, in a recording that I have not heard, starring Sophie Boulin and Kurt Streit. (Jacobs’s recording is no longer available except in used copies, nor is it on Spotify, but it can be found on YouTube these days. Stanley Sadie, a musicologist best known as editor-in-chief of the 1980 edition of Grove’s Dictionary of Music, complained that the microphones captured far too much thumping and other on-stage noises.)

The problem, in Gluck’s day, seems to have been that the audience wanted a work of high tragedy and rich characterization, such as the composer had given them several times before, including Iphigénie en Tauride. The latter work, which has been often performed and recorded in modern times, includes an aria that, as Berlioz pointed out, has an orchestral part that pointedly contradicts the words of calm that the singer (Orestes) claims to be feeling.

There is little such psychologizing in Écho et Narcisse. Many of the characters sing music that is tuneful, seductive, and lilting, clearly inspired by recent developments in Neapolitan opera. Or else straightforwardly yearning or lamenting. Still, the two main roles of Echo and Narcissus are often intense and “dramatically accented,” to quote the booklet-essay by Benoît Dratwicki. Dratwicki even proposes that, in this work, Gluck was attempting to fuse (or, I’d say, alternate!) French and Italian tastes, thereby resolving the “quarrel” that had arisen recently between supporters of Gluck (and the Lully/Campra/Rameau tradition) and of Piccinni and other composers from south of the Alps.

The work is not a tragedy but a “pastoral,” and this leads us to hear (and, if we were attending a performance, watch) numerous dances –sometimes with choral singing — for groups representing the Pleasures and Pains of Love (in the prologue) and for Nymphs and Sylvan Creatures (in Act 1). The dramatic tension rises when the nymph Echo, the ruler of the woods and waters, encounters Narcissus, who cannot respond to her affectionate entreaties because he is so obsessed with the reflection of his own beauty in the surface of the river. The rest of Act 1 and then Acts 2 and 3 show Echo gradually wasting away in misery, Narcissus suddenly awakening to the reality of her love for him, his arriving too late, and then Echo being brought back to life by Cupid (or “Amour” in French).

Tenor Sahy Ratia. Photo: Facebook

Gluck was apparently heartsick that the work did not succeed, and ended up leaving Paris — and operatic composition — forever, living out his last years in Vienna, the scene of some of his notable earlier successes (including Orpheus and Eurydice, the one opera of his that has a central place in the repertory today). But there may have been other reasons: he was already 65 years old and in ill health.

I found Écho et Narcisse quite enchanting. I don’t remotely mind hearing lovely singers and an almost lovelier early-instrument orchestra doing dozens of short graceful numbers, especially when the jollity and grace are relieved from time to time by moments of intensity, such as Echo’s statement (over quick repeated notes and slashing scales in the strings) to Narcissus’s friend Cyniras (Cynire) at the end of Act 1: “Hope has fled my heart. . . . The earth trembles beneath my footsteps!”

There are also effective numbers for two or more singers, such as a quartet near the end (for the lovers plus Cyniras and Cupid) when Echo is brought back to life: the excitement of the two lovers is splendidly reinforced by syncopated pulsing chords in the winds. And Gluck applies the principle of echoing in several musical numbers, including a funeral procession for chorus, soloists, and orchestra at the end of Act 2, and, in Act 3, a duet for Narcissus and, in response, the voice of the dead, aptly named, and soon-to-return Echo. I bet that opera lovers would respond as eagerly to this near-forgotten work by Gluck as they always do (understandably enough) to his Orpheus and Eurydice (whether the latter is done in Italian or in Gluck’s own later French adaptation).

Two of the most consistently enchanting singers here, appropriately, are Adriana González and Cyrille Dubois as the (eventual) lovers. I have praised Dubois previously in operas by Salieri, Halévy, Saint-Saëns, and Reynaldo Hahn; González is a new find for me! Myriam Leblanc’s name, too, is unfamiliar to me, but she is a welcome presence in the important recurring role of Cupid. The tenor singing the role of Cyniras, Sahy Ratia, is from Madagascar; his full family name at birth (in 1991) was Ratianarinaivo. Ratia’s voice is small but true, marred only occasionally by a slight shakiness (which disappears on higher notes). Indeed, everybody here shows grace, poise, and facility, and pronounces the French wonderfully.

A look at the performance of Écho et Narcisse in the palace of Versailles (conductor Hervé Niquet at far left). Photo: Operaphile

The multi-hued period-instrument orchestra is led by Hervé Niquet, one of France’s leading conductors of early music (and some nineteenth-century works as well). The recording comes from two unstaged performances in the Royal Opera House at the Versailles Chateau in October 2022. Applause has been mercifully removed.

The libretto and the fine essays are given in French, German, and English. The translations are attributed to two specific human beings and are, perhaps predictably, smoother and more reliable than the ones in other Versailles Spectacles releases, where they were done by a translation firm (or perhaps, as I at times wondered, by a machine). But there is no mention, in the printed libretto (though there is in the tracklist), that the opera ends with two orchestral numbers: dances, I assume. Some unwary listeners might pop the CD out prematurely and miss two more jewels, splendidly mounted by Monsieur Niquet!

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Adriana González, Christoph Willibald von Gluck, Cyrille Dubois, Écho et Narcisse, Hervé Niquet, Le Concert Spirituel