Opera Review: Saint-Saëns’s “Phryné” — Short and Witty, and Rediscovered

By Ralph P. Locke

A one-hour opera that the world forgot — a world-premiere recording of Saint-Saëns’s Phryné.

Saint-Saëns’s Phryné

Florie Valiquette (Phryné), Anaïs Constans (Lampito), Cyrille Dubois (Nicias), Francois Rougier (Cynalopex), Thomas Dolié (Dicéphile), Patrick Bolleire (Agoragine/A Herald)

Florie Valiquette (Phryné), Anaïs Constans (Lampito), Cyrille Dubois (Nicias), Francois Rougier (Cynalopex), Thomas Dolié (Dicéphile), Patrick Bolleire (Agoragine/A Herald)

Concert Spirituel Chorus, Rouen Normandie Opera Orchestra, cond. Hervé Niquet

Bru Zane 1047—65 minutes

To purchase, click here. To hear what’s in each track, click here.

I have drawn attention here at The Arts Fuse to a number of important but largely neglected short operas, most of them in one act (or two or three very short acts). One-act operas “don’t get much respect” in an operatic culture that tends to be obsessed with grandeur and high intensity: yes, most of the shorter operas are intimate, and many are quite humorous and conversational. They therefore do best in a small space, often with singers who can convey subtle nuances, accompanied by the slightest of facial and hand gestures that would get lost in the vast halls that we have been building (or at least using) for opera over the past century, such as the Met in New York and the Civic Opera Building in Chicago (home to Lyric Opera of Chicago).

At the Arts Fuse I have already reviewed, with pleasure, recordings of short operas by Saint-Saëns, Pauline Viardot, Reynaldo Hahn, Granados, Zemlinsky, Lennox Berkeley, the Swiss composer Richard Flury, and Boston-based Marti Epstein. The letter carrier has now brought me another short Saint-Saëns gem, produced (as was the previous one) by the Center for French Romantic Music, which is located at the Palazzetto Bru Zane (in Venice, Italy).

The Palazzetto’s “Bru Zane” label has risen to become one of the most important for classical and light-classical music (including operetta) over the past decade-plus. The Bru Zane recordings are devoted entirely to forgotten French works, some of which were quite popular in their own day. The scores are carefully edited, from the best surviving sources, by scholars at the Center. And each CD set is accompanied by a small hardcover book containing informative, trenchant essays, often by noted specialist scholars, plus any sung text and stage directions, all in French and good English. The firm’s early releases were misleadingly labeled, on the book’s spine, Ediciones Singulares (and were given ordering numbers that began with “ES”); but that was simply the name of the book printer.

Over the past decade or so, Bru Zane has brought us major works by Johann Christian Bach (yes, an opera he wrote in French, for the Paris Opéra!), Spontini, Gounod, Offenbach, Lalo, Massenet, Reynaldo Hahn, and others. And four little-known operas by Saint-Saëns.

Well, now make that five, and the latest is shorter than most of those (the exception being the delectable one-act La princesse jaune) but no whit inferior in inspiration and finesse. Phryné was first performed in 1893, in a version with lively spoken dialogue between the musical numbers, just as in most examples of opéra-comique and opéra-bouffe of the period, though in this case the dialogue was in verse, not prose. Three years later, André Messager composed recitatives so that Phryné could be performed in theaters in Italy and elsewhere that required that a work be entirely sung. (Carmen, similarly, got its dialogue turned into recitative for performances abroad.)

It’s the all-sung version that we hear here, splendidly put forth by a cast headed by Florie Valiquette (by turns voluptuous and, during coloratura moments, fluent and airy) and Cyrille Dubois (one of my favorite light tenors right now), under the lively baton of Hervé Niquet. The numerous brief contributions from the chorus are intoned with exquisite control and dramatic punch.

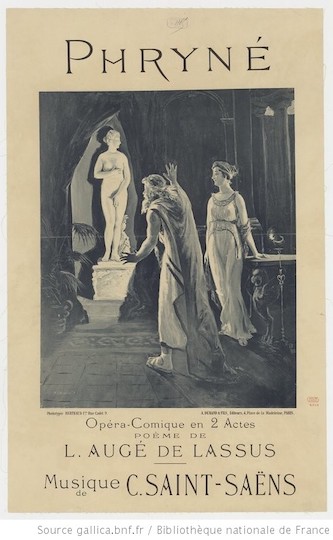

This engaging work is based on the historical (or perhaps semi-legendary) figure from ancient Greek history known as Phryné. Her beauty was so perfect and complete that, it is said, the great sculptor Praxiteles used her as the model for a statue that became widely admired and copied. One also reads that Phryné was accused of profaning the Eleusinian mysteries and was brought before the Areopagus (the high court in Athens). Reportedly, she or her lawyer revealed part of her body, and she was acquitted because her beauty was so divinely perfect.

This engaging work is based on the historical (or perhaps semi-legendary) figure from ancient Greek history known as Phryné. Her beauty was so perfect and complete that, it is said, the great sculptor Praxiteles used her as the model for a statue that became widely admired and copied. One also reads that Phryné was accused of profaning the Eleusinian mysteries and was brought before the Areopagus (the high court in Athens). Reportedly, she or her lawyer revealed part of her body, and she was acquitted because her beauty was so divinely perfect.

Well, this was not a plot that could be enacted in literal detail at the Opéra-Comique in 1893, but Saint-Saëns adapted a play that used the famous episode as a way of twitting the self-importance and hypocrisy of the wealthy men who ruled ancient Athens (or, one might imagine, 1893 Paris, or almost any city today). Briefly, the important leader Dicéphile falls for the beautiful Phryné, who, however, loves the old man’s spendthrift nephew Nicias. (This is not the same Nicias as the one in Massenet’s Thaïs.) Phryné tricks Dicéphile into visiting her, where she seems to promise him access to her, only to show him . . . the naked statue. Nicias enters and finds his uncle prostrate in front of the statue. Dicéphile is humiliated, and fears lest Nicias report his misbehavior (presumably including what he had intended to do when he showed up at Phryné’s). He thus agrees to give Nicias the large inheritance to which the latter has been entitled for a while (having come of age), and the two young people, it is implied, are now free to live a happy, comfortable life together.

The music is tuneful, colorful (lots of lovely wind solos), evocative of the ancient world (some modal melodies sung in unison with plucked or arpeggiated accompaniment), and always supportive of the particular moment in the plot. Several solos and ensembles could become standard items in concerts and on recital discs: Nicias’s “O ma Phryné,” Dicéphile’s ultra-brief “L’homme n’est pas sans défaut,” Phryné’s “Un soir j’errais” (followed by a gorgeous little trio with her servant Lampito—a trouser role—and Nicias) or Lampito’s “C’est ici qu’habite Phryné.” Critics pointed out the Offenbach-like cut of certain lighter moments. (I suspect some influence also from Berlioz’s Benvenuto Cellini.) They less often mentioned the numerous lovely moments of real sentiment (between Phryné and Nicias) and the wonderfully realized passages of satirical pomp and fake grandeur (one of which perhaps influenced the opening music of Virgil Thomson’s Four Saints in Three Acts).

I thought I picked up a slight reminder of one melodic moment in Bizet’s gorgeous one-act Djamileh. There are definitely some parallels to phrases and modulatory devices in Saint-Saëns’s own Samson et Dalila, just as one finds similarities between any two operas by Verdi (or between any two by Wagner). None of these familiar moments and devices from other Saint-Saëns works creates a problem: the opera is a swift succession of delights, worth savoring repeatedly. For further insight into the rich musicodramatic imagination at work in Phryné, I recommend the chapter in Hugh Macdonald’s recent Saint-Saëns and the Theater, a book rightly praised by reviewers as “magisterial.”

The recitatives that Messager composed to replace the spoken dialogue are extensive (unlike the super-concise ones that Ernest Guiraud created for Carmen) and beautifully worked out, making savvy use of motives from Saint-Saëns’s musical numbers. This is clearly the same composer whose alertness to character and drama are evident in Madame Chrysanthème, which had been performed for the first time just a few months before, or in his 1897 operetta Les p’tites Michu (see my review in the scholarly journal Nineteenth-Century Music Review).

I was often a bit unclear where a recitative ended and the next number began. The Bru Zane folks added to my confusion. Nearly every track starts with a recitative (by Messager) and flows into the aria, two-strophe song, brief duet, or whatever (by Saint-Saëns), making it impossible to jump to any given number that Saint-Saëns wrote. Worse, the track list prints the first words of each recitative, omitting the title of the subsequent number!

Soprano Florie Valiquette, by turns voluptuous and, during coloratura moments, fluent and airy. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

We could still use a recording with spoken dialogue between the numbers. But whatever record company tries this will need an all-French cast to do justice to the tightly worded and subtly witty spoken dialogue, as this cast does to Messager’s recitatives. Or else commission a witty translation, in the language of the cast.

A sharply characterized French radio broadcast from 1960 can be heard on YouTube, starring the stupendous Denise Duval (Poulenc’s favorite singer), but it largely jumps from one Saint-Saëns number to the next, making the story impossible to follow, despite the occasional clarification by a well-intentioned narrator.

In the meantime, here we have the all-sung version of one of Saint-Saëns’s most remarkable scores—for the first time ever, with many minutes of equally delectable Saint-Saëns-inspired Messager. For which all lovers of French music should thank the devoted scholars and organizers at the Palazzetto Bru Zane!

And, to close, a suggestion to organizers of opera festivals and college opera companies: two or three short works can be grouped together to make a diverse and diverting afternoon or evening. I’m imagining Saint-Saëns’s Phryné as the sparkling final item after, say, Granados’s passionate Goyescas and Menotti’s disturbing The Medium (or Rimsky-Korsakov’s eerie Mozart and Salieri).

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second is also an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: , Bru Zane, Cyrille Dubois, Florie Valiquette, Palazzetto Bru Zane

[…] Recordings Opera Review: Saint-Saëns’s “Phryné” — Short and Witty, and Rediscovered artfuse.org […]