Opera Review: Pauline Viardot’s and Ivan Turgenev’s First-Rate Fairy Opera Rediscovered

By Ralph P. Locke

Colorful, characterful, and full of worldly wisdom, The Last Sorcerer — by a skilled and imaginative composer, to a text by the great Russian novelist Turgenev– receives a superb world-premiere recording, with Met mezzo Jamie Barton and bass-baritone Eric Owens.

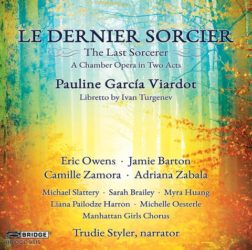

Pauline Viardot: Le Dernier Sorcier (chamber opera in one act). Camille Zamora (Stella), Adriana Zabala (Prince Lélio), Sarah Brailey (Verveine), Michael Slattery (Perlimpinpin), Jamie Barton (the Queen), Eric Owens (Krakamiche), Trudie Styler (narrator). Liana Pailodze Harron, Myra Huang, piano. Bridge Records 9515–67 minutes.

Pauline García Viardot (1821-1910) was one of the greatest opera singers of her day: a mezzo who was also an insightful actress. Meyerbeer composed for her the central role of Jean’s mother Fidès in Le prophète, and Berlioz made his famous version of Gluck’s Orphée et Eurydice to display her artistry. Viardot also inspired two major operatic roles that, because of advancing age, she did not end up performing: Berlioz’s Didon (in Les Troyens) and Saint-Saens’s Dalila.

Pauline García Viardot (1821-1910) was one of the greatest opera singers of her day: a mezzo who was also an insightful actress. Meyerbeer composed for her the central role of Jean’s mother Fidès in Le prophète, and Berlioz made his famous version of Gluck’s Orphée et Eurydice to display her artistry. Viardot also inspired two major operatic roles that, because of advancing age, she did not end up performing: Berlioz’s Didon (in Les Troyens) and Saint-Saens’s Dalila.

“Mme. Viardot” was also a close friend and confidante of George Sand, Chopin, and Gounod. The Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev, smitten with her, spent long stretches in Paris living with Pauline and her husband Louis Viardot (a theater administrator) and behaving as if he were a kind of family member. (A new book by cultural historian Orlando Figes uses their richly entangled lives and careers to explore the growing sense of cosmopolitanism in 19th-century Europe. It is entitled The Europeans: Three Lives and the Making of a Cosmopolitan Culture.)

Pauline Viardot was also a fine pianist and composer, and her songs and folk-song arrangements, with texts in French, German, Russian, and other languages, have been taken up by major singers (e.g., Cecilia Bartoli) and hailed by music historians and record reviewers.

Here we have the world-premiere recording of an hour-long chamber opera (with accompaniment for piano solo) that Viardot wrote to a French text by Turgenev. Its world-premiere performance took place in 1867 at Turgenev’s villa in Baden-Baden, with an illustrious audience in attendance (including Clara Schumann, soprano Giulia Grisi, and the German empress Augusta). Viardot herself performed the demanding piano part, and the roles were taken by her children, voice students, and — in the low-voiced role of Krakamiche — a friend of Turgenev’s. Some later performances used a chamber orchestration by Eduard Lassen (one performance of which was reportedly conducted by Brahms). Lassen’s version has been revived at times in recent years.

The recording offers all the musical numbers in the original piano-accompanied version. (Some excerpts can be heard on this informative video.) They were originally connected by spoken dialogue, but that text seems not to survive. Instead, we hear a spoken narration that prepares us for the next number. (On YouTube one can see a staged production of the work from the city of Jérez de la Frontera, in Spain. Someone has cobbled together the necessary spoken exchanges, in Spanish. Unfortunately, the singers are quite weak.)

The plot tells of Krakamiche, an aged sorcerer who has expropriated the lands of the forest fairies but, by this point, has lost most of his power. The fairies play tricks on him, and they enable Prince Lélio, who has wandered into the forest and fallen in love with the sorcerer’s daughter Stella, to gain her hand in marriage. The opera ends with Krakamiche, Stella, Lélio, and Krakamiche’s servant Perlimpinpin (a former giant, now greatly reduced) retiring to Lélio’s castle. The fairies celebrate the return of peace to the forest.

Turgenev built the plot around a process of rupture and eventual healing in the natural world. This theme has Russian overtones: we find it in, for example, Rimsky-Korsakov’s folk-song opera The Snow Maiden. But the characters’ names here are not Slavic-sounding, and the sole magical incantation that Krakamiche reads aloud from a book of Merlin’s magic spells is comically multiethnic, naming Astaroth, Beelzebub, Lucifer, Antropos (i.e., Human!), only to end with, yes, the Russian witch Baba Yaga. There is also a magic rose that enables Lélio to remain invisible to everyone except Stella. Except that the hapless guy drops the flower in the presence of Krakamiche, causing the latter to threaten him with the aforementioned spell, which, however, is ineffective and ends up making a goat appear instead.

All this might suggest a work that has little claim on our attention today. But in the highly proficient and sometimes magical premiere recording from Bridge Records, featuring two Metropolitan Opera stars and other fine performers, it proves to be a candy box of delights. The music is surprisingly varied (hunt style, gyrating-waltz style, etc.), and often quite comical, not least in the solo song of Perlimpinpin. The former giant grouses about how much better life was when he and his sorcerer-boss were powerful; in the process, he demonstrates his current incapacity by repeatedly failing to carry his own thoughts to completion.

Pauline Viardot. Photo: Wiki Commons.

Many passages are lyrical and touching, not least the duet for Krakamiche and Stella, in which the daughter expresses her desire to spread her wings and the father obsesses about regaining his former efficacy. The duet is in Spanish style, perhaps a tribute by the composer to her own distinguished father (the tenor and composer Manuel García). I particularly enjoyed the duet for the young lovers Stella and Lélio, in which their voices exquisitely intertwine. The fairies, including their queen and the impish Verveine, provide the opera with many moments of liveliness and conclude it with a paean to the peaceable forest.

The work’s harmonic language is relatively straightforward, a bit like early Fauré or such lighter-genre French composers as Delibes, Chabrier, and Messager. The intriguing march of the fairies, who are at this point pretending to be East Asian (“Cochinese”) dignitaries carrying a magical herb, hints, I think, at a well-known Russian or Ukrainian folk song known in German as “Schöne Minka.” (Beethoven wrote variations on it for flute and piano, Op. 107, no. 7. In 1940 it became a hit song for Dinah Shore, under the title “Yes, My Darling Daughter.” The jazz orchestra accompanying her was conducted by Gene Krupa.)

Bass-baritone Eric Owens and mezzo Jamie Barton, both Met stalwarts, are superb as Krakamiche and the Fairy Queen. Barton’s shimmer on high notes is fully the equal of her ripeness at the low end — this is marvelous singing. Owens’s voice is a little thick on this occasion, moving heavily on some short notes, but its heft helps us feel the power that this sorcerer once commanded. A more modestly endowed singer of a musical-comedy or operetta sort might play the role with more nimbleness and verbal variety. But would he sing as eloquently as Owens does Krakamiche’s farewell to the forest (in a gorgeous unaccompanied quartet, with Perlimpinpin and the two young lovers)?

Camille Zamora, an enterprising soprano, did much to pull the whole project together: she is listed as Executive Producer, and she also provided the booklet essay and the printed English translation of the libretto. Zamora sings Stella’s music with much feeling, though not always squarely on pitch. Some of her loud high notes are a bit fierce.

Rich-voiced mezzo Adriana Zabala plays the pants role of Prince Lélio to the hilt, occasionally coloring a single word without breaking the lyrical line. (Here she sings her Act 1 “hunting-horn” aria.) Tenor Michael Slattery is hilarious yet vocally smooth and enjoyable (never annoying) as Perlimpinpin. His command of French pronunciation and inflection is extremely convincing. Soprano Sarah Brailey is at once pert and mellifluous as the trouble-making fairy Verveine. (Verveine is the French word for the fragrant herb known in English as lemon verbena.)

Two superb pianists take turns playing the demanding, quasi-orchestral accompaniment. The connecting narration is read affectingly and with welcome variety and nuance by Trudie Styler, an actress who at times has collaborated with the pop musician Sting (to whom she is married). But Styler’s narration, recorded in a studio with no “room echo,” intrudes aurally each time. I would have preferred that the narrator speak in the same space as the singers.

Soprano Camille Zamora did much to pull the whole project together: she is listed as Executive Producer and also provided the booklet essay and the printed English translation of the libretto. Photo: artistbanner.

Also, the narrator’s summaries, drawn directly from Turgenev’s synopsis, are a bit prosaic. Nothing like, say, Peter Ustinov’s endlessly entertaining narration that takes the place of the original spoken dialogues in István Kertész’s recording of Kodály’s music for the Hungarian-language spoken-language opera Háry János.

One true oddity: the opera contains a minute-long scene of melodrama, in the technical sense of that word, namely spoken dialogue over instrumental music. The preceding narration implies that, during this brief scene, Krakamiche is trying to cast spells. The recording supplies the piano music, but without anything being spoken over it. Record collectors may recall similarly puzzling moments of word-deprived melodrama in recordings of incidental music intended for spoken plays, e.g., Mozart’s music for King Thamos or Mendelssohn’s for A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Still, if you ever thought that opera is sometimes an overblown genre and could profit from a bit of modesty, here’s a wonderful example of how that can be achieved. The Last Sorcerer could be performed in a small hall or even somebody’s living room. It lasts a mere hour, yet it addresses deep human issues and a wide range of feelings. Bridge Records, which came out last year with a superb first complete recording of Marc Blitzstein’s The Cradle Will Rock with the original orchestrations, deserves to be congratulated for taking a chance on this even more obscure but equally delightful and at times touching work.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to the online arts-magazines NewYorkArts.net, OperaToday.com, and the Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in OxfordMusicOnline (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review is based on one that first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here by kind permission.

Tagged: Bridge Records, Ivan Turgenev, Le Dernier Sorcier, Pauline Viardot