Film Retrospective: “Early Kiarostami” — One of Cinema’s Great Humanist Auteurs

By Betsy Sherman

Abbas Kiarostami was the most important filmmaker to come out of the New Iranian Cinema movement, which spawned works that became staples in film festivals worldwide from the late ’80s on.

Early Kiarostami – A retrospective at the Harvard Film Archive in Cambridge, through September 18. Films are in Farsi with English subtitles.

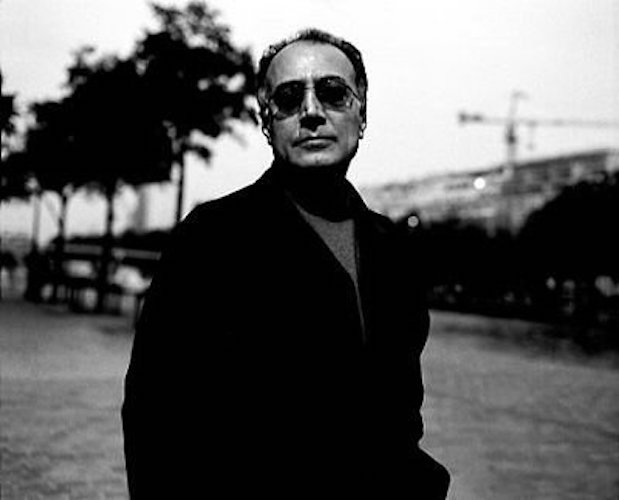

Iran’s Abbas Kiarostami — the most important filmmaker to come out of the New Iranian Cinema movement. Photo: Wikipedia

In 2016, cinema lost one of its great humanist auteurs. Iran’s Abbas Kiarostami belonged to the school of filmmakers who don’t create a world but capture a slice of it. His antecedents include the Italian neo-realists and the Indian director Satyajit Ray; his contemporaries include Taiwan’s Hou Hsiao-hsien and Belgium’s Dardenne brothers; and his descendants include young independents such as Chloé Zhao. Anyone who’s seen the moral-dilemma dramas of Iranian double-Oscar-winner Asghar Farhadi (A Separation, The Salesman) should know that ground was broken for him by Kiarostami.

The Harvard Film Archive’s retrospective of Kiarostami’s work, planned for 2020, arrives at last, but split into two parts, the first now, the second in the winter of 2023. The director made a memorable visit to the HFA’s Carpenter Center cinema in the spring of 2000.

Kiarostami was the most important filmmaker to come out of the New Iranian Cinema movement, which spawned works that became staples in film festivals worldwide from the late ’80s on. But he got his start decades earlier. Kiarostami’s career straddled two ways of life, that lived during the dictatorship of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, and that lived after Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution. Before the revolution, Iran had a thriving commercial industry, with crowd-pleasing genre films akin to those made by Bollywood, as well as a subset of more serious fare. The industry ground to a halt upon the revolution, as the nascent theocracy wrestled with what sort of a national cinema it could live with. That turned out to be a medium under strict censorship (prohibitions included no contact between men and women on screen, and a woman’s hair had to be covered even when she was shown in her own home).

Not a person who grew up impassioned about cinema — he much preferred talking about Persian poetry — Kiarostami developed an unconventional approach to making movies. He entered a project without a firm script in hand, established a remarkable rapport with the nonactors who peopled his films, and let the story germinate, allowing for improvisation and happy accident. His films feel more like a series of linked questions than a narrative path that leads to an incontrovertible answer. Writer/filmmaker Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa called his storytelling style a cinema of ellipses and omissions. Kiarostami said that he built open spaces into his films out of respect for the viewers, whom he felt capable of filling them in and connecting seemingly disparate vignettes. Indeed, a Kiarostami movie makes you lean forward into it, and affords a deepened experience with each viewing.

The centerpiece of Early Kiarostami is what has become known as the Koker trilogy, although it was not planned as a trilogy in advance. Where Is the Friend’s House?, And Life Goes On, and Through the Olive Trees will each be shown twice, on a Friday night and a Sunday afternoon.

A scene from Where Is the Friend’s House? — A parable-like story about how precious and monumental a simple act of compassion can be.

The masterful Where Is the Friend’s House? (1986) is the perfect opener for the series. With a light touch, Kiarostami shows in this parable-like story how precious and monumental a simple act of compassion can be. The feature is the culmination of Kiarostami’s many years working with children, and reflects his strategies for imbuing meaning into his films while not crossing the censors. It didn’t hurt that he was working far away from the authorities in Tehran; the film’s locations are Koker, a farming village 200 miles northwest of the capital, and the neighboring village of Poshteh.

Eight-year-old Ahmad sits uneasily by as his tearful deskmate Mohammed Reza is scolded by the teacher for having misplaced his homework notebook again. When Ahmad goes home and discovers he has taken Mohammed Reza’s notebook by mistake, he’s determined to return it. While he’s supposed to be buying bread, Ahmad searches for his friend’s house, but he doesn’t know the address and can’t find anyone to help him. Ahmad can’t conceive of not doing everything he can to keep his friend from getting in trouble. He hardly even speaks, and when he does he has to repeat his words because adults just do not hear him. By the end of the film, the unyielding child has been gently transformed into a hero. Similarly, the notebook becomes a symbol of honor; it physically hurts to witness a contractor snatch it away from Ahmad and rip out a page on which to write.

Friend’s House was so beloved in Iran that when an earthquake hit northern Iran in 1990, killing 50,000, there was nationwide concern about whether the boys who played the two main roles in the movie (brothers Babak and Ahmad Ahmadpour) had survived. Kiarostami drove with his 11-year-old son to the devastated area the third day after the quake to look for them. And Life Goes On a.k.a. Life, and Nothing More (1992) is a fictional re-creation of that search. In it, a middle-class film director and his spoiled but curious son talk to a variety of earthquake survivors as they drive on choked roads to the villages in which Friend’s House was filmed, searching for the Ahmadpour brothers. Shooting took place in two parts, five and 11 months after the earthquake.

Where Is the Friend’s House? was told in a conventional narrative style, but thereafter, the Koker movies took on a self-reflexive dimension, raising questions about using an inherently deceptive medium like film to get at the truth, and about the artist’s place in society. Actually, these matters, and a blurring of documentary and fiction, were kick-started by Kiarostami’s 1990 Close-Up, which will be included in part two of the series.

And Life Goes On pays tribute to the residents’ resilience, but always at a very human level; for example, much effort is put into reinstalling a TV antenna, so they won’t miss the soccer World Cup. The lead, Farhad Kheradmand, wasn’t an actor, but an economist; he learned to drive for the film. The car, which valiantly makes its way through the ravaged mountain landscape, becomes a character in its own right.

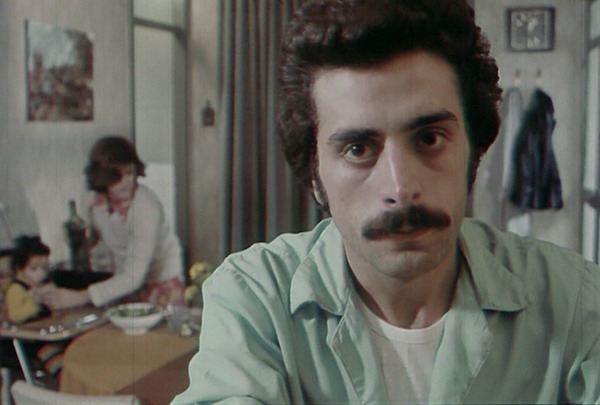

A scene from And Life Goes On

A four-minute scene in And Life Goes On concerns a man who tells of being wed right after the earthquake hit. Through the Olive Trees (1994) uses this nonactor, Hossein Rezai, as its hapless hero. In this fictionalized movie about the making of the previous movie, the hook is that the woman who has been cast to play Hossein’s bride in And Life Goes On is the woman he is genuinely in love with — and she barely acknowledges his existence. The Kiarostami surrogate here (called “the director”) is played by Mohammad Ali Keshavarz, a rare case of the casting of a veteran actor. It’s downright dizzying to watch surrogate Keshavarz directing surrogate Kheradmand — while they’re both in reality being directed by Kiarostami.

But the film belongs to Hossein, the delightfully stubborn gofer who sees his chance to act in the film as an opportunity to impress his beloved. There are two strong women’s roles in the movie, the young actress Tahereh and the director’s assistant Mrs. Shiva. Olive Trees culminates in one of those Kiarostami ellipses, as the director character watches, but cannot hear, what’s going on between the young man and woman in an olive grove.

Hallmarks of the trilogy that would persist in Kiarostami’s oeuvre include long shots, in terms of distance from the camera (these cool the emotional impact), and shots of long duration, which make room for spontaneity. Kiarostami’s mid-period films tend to unfold in exteriors. His love of landscape extended to his work as a photographer (he had exhibitions worldwide). A zigzag path that he had carved into a hill for Friend’s House, with a lonely tree at the top of the hill, became the iconic image for the Koker films.

Born in 1940 in Tehran, Kiarostami studied painting at that city’s University of Fine Arts. Initially a graphic artist, he designed film credit sequences and directed commercials in the ’60s. In the ’70s, he helped establish the filmmaking department at Iran’s Institute for Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (known as Kanoon). Through films made about children — almost exclusively boys — for Kanoon, Kiarostami developed a storytelling manner that presented moral dilemmas with economy and immediacy, and speculated on their resolution with wit and empathy rather than heavy-handed didacticism. There are no professional child actors here, it’s strictly first-timers, with whom the director honed his casting skills.

Those familiar with educational films by the National Film Board of Canada, and its standout filmmaker Norman McLaren (these were a feature of my school days) may sense a resemblance. Kiarostami hadn’t seen the films at the time, but he did get a sense of them from a catalogue he got hold of.

These early shorts and features trace the evolution that led to the trilogy, and the HFA series provides a rare chance to see them in a theater. Shorts will accompany most of the features.

A scene from the Kiarostami short Bread and Alley.

Kiarostami’s debut short, Bread and Alley (1970), puts us in the shoes of a little boy going home from an errand to buy bread, walking through zig-zagging alleyways. He’s suddenly confronted by a large dog. After trying to find alternate routes, the boy must brainstorm through his fear to reach a truce with his foe. Music includes a jazz instrumental of Ob-la-di Ob-la-da. On the basis of this short, Kiarostami was awarded a scholarship from the Czech government and spent six months in Prague working at a film studio.

Breaktime (1972) is Kiarostami’s first depiction of the punishment of students, this one a boy who’s broken a school window while playing soccer and is beaten for it. He then tries to join in a street game and experiences a different kind of estrangement. With this short, the director explored the aesthetics of using space.

The Experience (1973) (which wasn’t available for preview) is an hour-long film about an errand boy at a photography shop who’s infatuated with a middle-class girl.

The Traveler (1974) is the last of Kiarostami’s black-and-white films. This subtle and affecting feature is based on a story by Hassan Rafie. Its protagonist is a far-from-perfect poor rural boy whose life revolves around soccer. Qasem (young first-time actor Hasan Darabi never tries to ingratiate himself to an audience) is determined to run away to see his favorite team play an important match in Tehran and schemes to get the bus fare and ticket money by any means necessary. He tells a series of breathtaking lies, manipulates his timid friend, trades on his father’s good reputation, and exploits little children via a strategy that, when you think about it, indicts cinema itself. He accomplishes some, but not all, of his goals, leading to a poetically shot conclusion. The Traveler casts its eye on a system in which poor boys are kept in their place. Even Qasem’s illiterate, hard-working mother is complicit, handing him over to the headmaster for a beating.

There’s much sensual pleasure in the compositions and rhythmic editing of The Colors (1975), which shows examples of similarly colored objects, and How to Make Use of Leisure Time: Painting (1977). The latter short suggests that helping around the home — in this case learning how to prep and carry out painting jobs on doors, furniture, etc. — can be fun and transform one’s environment.

A scene from the Kiarostami short So Can I.

So Can I (1975) is a morsel in which footage of various animals is shown to two schoolboys. One of them acts out whatever that animal can do — until they’re shown a bird in flight (humbling, ain’t it?). Two Solutions for One Problem (1975) is a key work in the director’s Kanoon canon. Schoolboy Dara borrows his friend Nader’s textbook and returns it with its cover torn. The result could be anger, escalating destruction, and a tussle — or maybe there’s another way. This gem of a movie is an ode to constructive problem-solving (as Alan Arkin and his wife used to say on Sesame Street, “Cooperate!”).

Solution (1978) reminded me of Norman McLaren’s live-action shorts. There’s no dialogue in this vignette about a man trying to hitchhike on a cold mountain road; he’s carrying a replacement tire to put on his car that’s quite a trek away. With no one to accommodate him, he and the tire — companions, you could say — find a way to get there.

A Wedding Suit (1976) right off the bat says something about social class, as a teenage tailor’s apprentice is tasked with helping to make a suit for a rich boy around his age. A kid with few options is contrasted with a kid with many. But this film isn’t a pity-party about Ali, the apprentice. He plays a perilous game that provides some tense comedy: by night, he barters the use of the suit to his friends, fellow working boys who’d never be able to afford one. What could possibly go wrong? As someone who has seen a lot of post-revolution Iranian film, I was startled to see flirting, an unchaperoned date, and a mixed-gender karate class.

A scene from the feature The Report.

The Report (1977) is a two-pronged drama. Through its lead character Mohammad Firuzkuhi, a tax collector in Tehran, it examines corruption in government. It also explores his home life, showing domestic abuse within an unhappy marriage. The workplace story might be more meaningful to those familiar with the late stage of the Shah’s regime. But anyone can recognize a degree of rot here, with callous and cynical functionaries looking down on the public. Mohammad is accused of demanding bribes, which he (not very convincingly) denies. We’ve already witnessed the tetchy relationship between him and his wife. When things hit the boiling point, he lashes out at her and uses their little daughter as a pawn (he doesn’t treat her very well, either). Lead actor Kurosh Afsharpanah is opaque, imprisoned by his brooding. The wife is played by Shoreh Agdashloo in her early days as an actress, before she left Iran and went on to a successful career in Hollywood. Unfortunately, she doesn’t get much more to do than be sullen and angry. The film was made when Kiarostami’s own marriage was breaking up.

A notable instance of a film that encompasses material from before and after the revolution, First Case, Second Case (1979) has a staged component that is then commented on in interviews. In a boy’s high school classroom, the teacher draws an ear on the blackboard and tries to teach a lesson, but is interrupted by a student’s deliberate banging. He banishes the entire last row to the corridor, saying he’ll let them back in if the offender is identified. Two possibilities are filmed, one in which someone informs, and one in which the boys stay silent in solidarity. A surprisingly diverse group of adults comment on the scenarios. Some are parents of the boys, others educators, others community and religious leaders. With fresh memories of the Shah’s secret police, and uncertainty about what the revolution would bring, the issue is provocative; however, the talking heads format does become fatiguing cinematically. The HFA will have a guest speaker, Mahan Maolemi, to put this interesting work (banned by the Islamic regime) in context.

The Chorus (1982) is a sweet little story that nevertheless has some bite. An elderly man is susceptible to danger in the streets if his hearing aid should malfunction. But, when he chooses to turn it off, it’s his protest against the noisy modern world. He finds peace in his apartment where he insists all sounds be muffled, but that risks losing a vital link with the outside. A cheerful collective of head-scarved little girls lend their robust voices to the efforts of two special visitors to get the man’s attention.

Orderly or Disorderly? (1981) is a sly experimental work. It starts out as a Goofus and Gallant-type behavior lesson. First, a sequence in which schoolboys leave class in an orderly fashion is followed by one depicting a chaotic, time-consuming free-for-all. Then the story goes meta, as, on the soundtrack, Kiarostami and his crew discuss what’s on screen and how it could be clarified. Eventually, the film becomes a commentary on one of Kiarostami’s pet peeves, terrible traffic, which here involves bad pedestrians as well as bad drivers.

A scene from the feature Homework.

The extraordinary Homework (1988) was a step even further toward bringing transparency to the documentary form. This time, Kiarostami put himself and crew in full view, which reminds the audience that they’re watching a film. He is sometimes in the same shot with his subjects, a succession of young boys who attend a poor public school in Tehran. The documentary is framed as an investigation sparked by a personal agenda. Kiarostami wonders how he can get his own son to do his homework. Each speaker is interviewed by the director, who tries to cut through the boys’ tendency to say what they think adults want to hear (such as, that they prefer homework to cartoons). These kids are beaten at home, beaten at school, and many have illiterate parents (they might get some help with their studies from siblings or neighbors). The Iran-Iraq war (1980-88) is ever present. The boys are shown chanting enthusiastically at a patriotic rally in the schoolyard. Homework will be introduced by Mahan Maolemi.

Further post-revolution works Fellow Citizen (1983) and First Graders (1984) weren’t available for preview. The first is a documentary that spotlights a Tehran traffic officer, a riff on the director’s favorite pet peeve — impossible traffic and bad drivers. The second visits another favored topic, the disciplining of children, this time set in a school in a poor neighborhood.

The winter continuation of the retrospective will put on display Kiarostami’s evolving strategies to work within and critique the system of censorship in Iran, and his move to international locations. Its screening of Close-Up will be introduced by Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf, currently a Radcliffe Fellow, who figures into the subject matter and makes a cameo appearance.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for the Boston Globe, Boston Phoenix, and Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

Tagged: Abbas Kiarostami, And Life Goes On, Betsy Sherman, Early Kiarostami, New Iranian Cinema, Through the Olive Trees

Mrs. Sherman.

As an Iranian-American, a kiarostami fan, and a cinema student, I was moved by your honest, precise, and educational article, Early Kiarostami. Being familiar with the political situation in Iran quite well and the scrutiny filmmakers in Iran are under for their craft, one should appreciate more such a filmmaker and his works with a universal voice. Thanks again for reminding the world the legacy of such humanist as Abbas.

Reza.E.