Book Review: “The Undercurrents” — History as a Whisper in Your Mind

By Thomas Filbin

Kirsty Bell’s psychological-cultural-topographical-historical walking tour of Berlin is an idiosyncratic delight.

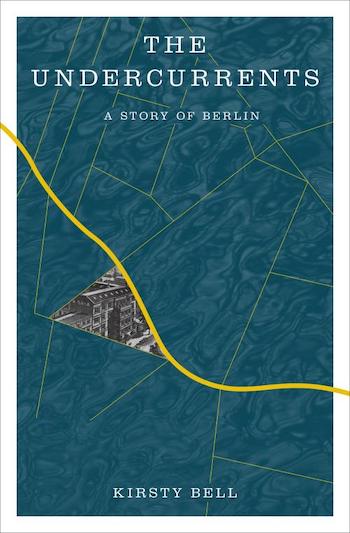

The Undercurrents: A Story of Berlin by Kirsty Bell. Other Press. 385pp. $18.99

Fernweh!

Fernweh!

The Germans like to string a succession of short words together to form a single word that embraces a concept. Derfallschirmspringerschule is “the parachuting school,” while a Funejahresdervertag is a “five-year contract.” My favorite word, partly because of its charming brevity, is Fernweh, which refers to homesickness for a place you have never been, a longing for an illusion that cannot be logically explained but is deeply felt nonetheless. Fernweh is how I felt about Berlin while reading Kirsty Bell’s psychological-cultural-topographical-historical walking tour of the city, where she has resided for two decades.

Bell, a British-American writer and art critic, left New York in 2001 to live with her German boyfriend, later husband, in Berlin. It was after the fall of communism and German unification, and Bell writes that she felt “belated”: artists, writers, filmmakers, and actors had arrived before her to become part of the city’s renaissance. She loved Berlin but, after a decade of marriage and two sons, her world changed when the relationship collapsed, almost without her seeing the tell-tale signs. Remaining in Berlin with shared custody, Bell decided to find the time on her own to become acquainted — in an idiosyncratic way — with the metropolis. The Undercurrents is the splendid result, a narrative driven by a spirit of curiosity and serendipity, very much in the spirit of flâneur Walter Benjamin (in some ways Bell’s patron saint). The book is a speculative excursion, a writer celebrating a search for place, time, and self.

“There are things you can see and others you can only feel, that you sense in a different way, as a whisper in your mind, or a weight in your bones,” Bell observes of her method. The perceptual journey she takes us on is subjective, impressionistic — it is more about things absorbed than history elucidated. Water is one of her motifs, inspired by the fact that she had moved into an apartment on the banks of the Landwehr Canal, whose enormous beauty becomes hazardous at the time of seasonal flooding. She accepts this duality with a laconic stoicism: nature is larger than we are and not susceptible to our wishes.

Buildings and their provenance fascinate Bell. She plows through deeds, drawings, and plans in order to tell the stories of selected structures. A man named Zimmerman built on a plot of land that she examines. She plays around with the meaning: the word in German is an occupational surname for a carpenter, but it can also be interpreted as “maker of rooms” — a more poetic image. Bell’s keen ear for excavating language is also exhibited when she talks about the breakup of the marriage. When looking at a new place to live with her husband, she broaches the subject of their future happiness: “My husband’s answer, remote and dulled, seemed dredged up from an ocean bed. Ich bin nicht unzufrieden. I am not unsatisfied. So many things were left unsaid.”

Literary Berlin is not neglected. One December afternoon in her wanderings she stops for coffee and picks up the Berliner Zeitung lying on the table with an article commemorating the upcoming bicentenary of the birth of Berlin’s famed 19th-century author Theodor Fontane (1819-1898). She is fascinated by the article’s title Sich treiben lassen (“Let yourself drift”). She reads with pleasure that “Fontane’s way of thinking and writing did not follow a compulsive urge toward completion … he believed far more in moods and coincidence than the need for comprehensiveness.” The impetus behind Bell’s book is the same: she is not after neat explanations but evocations of the emotional power of where one finds oneself. She embraces a kind of “eternal present” in which consciousness rules.

Writer and art critic Kirsty Bell. Photo: J. Baier

One of the book’s heroines is Marie von Bunsen, a woman who never married and used her financial independence to hold salons on Sunday mornings (starting in 1900) for writers, artists, thinkers, diplomats, and generally interesting people. Bell calls these gatherings a kind of tableau vivant of conversation — it was also a dress rehearsal for female emancipation. Revolutionary Rosa Luxembourg, who had moved to Berlin from Zurich in 1898, represents a proletarian version of von Bunsen. Her opposition to World War I, compounded by her writing and speaking, made her a radical threat to those in the prowar establishment — left and right. The ’20s brought Dada and violent disillusion to a civilization that — contrary to its own rationality — ending up leading Europe into a conflagration that nearly killed off a whole generation of men. Bell reflects on the disgust felt by Bertolt Brecht, Thomas Mann, and George Grosz, artists and cultural figures who defined a generational mood of opposition.

Bell’s investigation of Berlin goes into how the German rail system was the most extensive in Europe. Constructed as an economic good, it later became a tool for the massive deportations of Jews to concentration camps in wooden-slatted cars intended for cattle. 30 to 50 cars a day arrived at Treblinka or Sobibor, horrific tributes to legendary German efficiency. Postwar Berlin was in ruins, rebuilt but divided among the Allies into zones. For Bell, the fall of the Berlin Wall was a political and cultural event that opened the door for a fruitful rebirth — once more Berlin would become Germany’s proud capital. The downside of renewed prosperity was predictable: gentrification and the arrival of widespread homogenization. Bell laments that the distinctive color and character of the city she loves are changing, a transformation that includes a loss of energy and complexity that comes when historical connections are severed.

Some readers, in search of a detailed history, might find this book too subjective, too personal. But, to me, it is this freewheeling approach that makes The Undercurrents such an impressive achievement. Prefabricated structure is ditched — Bell wanders through time and space articulating and meditating on her impressions. Benjamin would approve; he posited that genuine understanding and appreciation were about chance intake and then quiet analysis. His fascinating (though uncompleted) Arcades Project was about comprehending Paris by viewing its streets, alert to delicate paradoxes in the inscrutable cityscape. Edmund White’s 2001 The Flaneur continued this imaginative research. For the flâneur, to perceive and then reflect becomes part of the history of a place — it is also (perhaps) the highest state of being. Bell’s unconventional examination of Berlin is a potent contribution to that modernist tradition — it is not only a pleasure to read but a spur to further contemplation.

Thomas Filbin is a freelance critic whose work has appeared in the New York Times Book Review, Boston Sunday Globe, and Hudson Review.