TV Review: “Barry” — An Inevitable Season Four

By Jason M. Rubin

What made Barry such a hit was that it was deliciously funny; the laughs were a balm for the uneasiness viewers felt as the body count rose from episode to episode.

Warning: *SPOILERS* Ahead

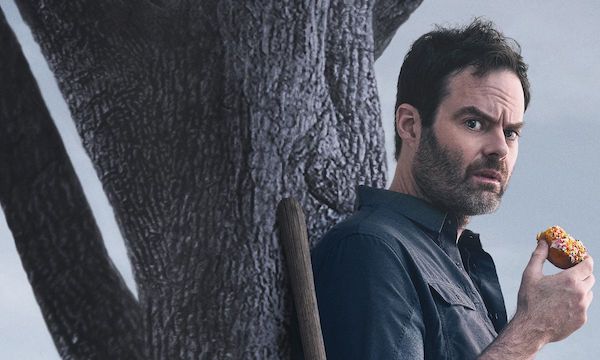

Bill Hader in Barry. Photo: HBO

I suppose there was no fully satisfying way to end the TV series Barry. Since its inception, every character put their flawed foot forward as they spiraled down to almost primitive levels of fear, shame, anger, and grief. No one in this cast of characters was worth rooting for, yet we wanted the best for each of them because they were so richly written and performed. At the same time, we knew that wasn’t going to happen. There was a cognitive dissonance at the beginning: viewers celebrated Bill Hader’s titular character (a hit man who believed he could change) as a hero because of his ridiculously efficient ability to shoot up a room of bad guys like a Gen X Dirty Harry. That shifted over time, as we saw that Barry was irredeemable. There were two possibly sympathetic characters during the four-season run: Barry’s ex-Marine friend Chris and Janice, the police detective who was also the love interest of acting coach Gene (Henry Winkler). Barry killed them both.

What made the series such a hit, earning 44 Emmy nominations (winning nine) to date, was that it was deliciously funny; the laughs were a balm for the uneasiness viewers felt as the body count rose from episode to episode. But, after a Covid-enforced hiatus between seasons two and three, the series returned even darker: many of the yuks were traded for explosions of psychological turmoil. Even the sets changed. Gene’s acting studio, where so much of the comedy played out, was gone, replaced by a vast empty landscape that became a key symbolic feature of both flashbacks and the jarring fourth-season flash forward. Gene himself underwent a major transformation. While his insatiable ego continued to get him into trouble, without his studio (and his girlfriend) he was adrift, easily manipulated by anyone who needed something from him.

The most striking change in character, though, might have been that of Chechen wannabe warlord NoHo Hank, who went from charmingly funny to tragically ambitious. In the beginning, Hank could make the audience laugh with just a facial expression. But over the last two seasons he became serious and unforgiving — mirroring the surprising arc of Nate in Ted Lasso. As Barry’s love interest, Sally broke away from the acting studio and finally landed her opportunity in La La Land. But having cut the cord with the studio — where she at least had the confidence to rightly declare she was the most talented in the room — she was soon lost in the hypocrisy and shallowness of show business. When she and Barry ran away together midway into Season 4, you knew she (and Barry as well) would become hopelessly lost, untethered, and deeply unhappy.

As for Barry’s character, in the latter seasons he was always unshaven, always unkempt, always off balance. Perhaps coinciding with his apparent conversion to a religious lifestyle, his instincts began to fail him — he became easy to ambush. The saddest part of Barry’s psychopathology is that he not only believes he can redeem himself, he also thinks he can make it up to Gene by getting him back into the business. At no point (except maybe at the end of the series finale, when Gene plants a bullet in his head like Michael Corleone and the police captain), does Barry understand that you can’t murder someone’s girlfriend and still get to be friends.

And then there’s Fuches, Barry’s mentor, father figure, and murder pimp. Fuches went through multiple bouts of torture throughout the series, toggling back and forth between being Barry’s protector and Barry’s prey. At the end, though, when it seemed that Barry and Sally’s son John was in danger of being caught in a deadly crossfire, it was Fuches who not only kept the child safe from harm, but also delivered him back to his grateful parents. At last, after 32 episodes, a true hero emerged in this series.

Oddly enough, the thing that unsettled me the most is that the explosive Barry theme music (“Change for the World” by Charles Bradley) went unused for the entire last season. Its absence brought out the starkness of the show’s narrative and the series’ overarching message that entertainment is ephemeral, guilt burns hot as the desert sun, and death is unending silence.

All of this is to say that Barry was just as good in Season 4 as it was in Season 1, just with less humor and more psychological depth. From the get-go, the thing that I admired most about the show was that Hader always played against type. He rarely delivered the show’s comedy and, when he did, he eschewed the things that made him famous on SNL, namely his impressions. While he had shown some acting prowess in films such as The Skeleton Key, no one could have expected Hader to win two Emmys for Best Actor. But he did, and they were well deserved. In fact, all the key characters — Barry, Sally, Gene, Hank, and Fuches — were perfectly cast and the respective actors totally owned their characters, both their good qualities and their faults. It was a rich ensemble and Hader’s directing (much of the series, and all of Season 4) makes a strong case for him to be an A-list director in television and perhaps in motion pictures as well.

As emotionally draining as Barry could be, it was short by today’s standards: just eight half-hours each of its four seasons. The aforementioned Ted Lasso (also now finalized) delivered its exceptional stories by the hour, as do many other series. Barry delivered concentrated storytelling, with characters so complex that viewers spend the next half hour processing what they just saw. I plan to binge the entire series and look for the bread crumbs Hader had sown throughout, which ultimately led to the hard justice meted out in the series finale.

It was clear from the start of Barry that there would be no happy endings for any of the characters. Those still alive at the end are scarred (and scared) for life; those who perished received the only ending that could have made sense — or at least it can be said that they got what was coming to them. Barry’s final utterance in the series, “Oh wow,” was supremely fitting.

Jason M. Rubin has been a professional writer for nearly 40 years, more than half of those as senior creative lead at Libretto Inc., a Boston-based strategic communications agency, where he has won awards for his copywriting. He has written for Arts Fuse since 2012. Jason’s first novel, The Grave & The Gay, based on a 17th-century English folk ballad, was published in September 2012. Ancient Tales Newly Told, released in March 2019, includes an updated version of his first novel along with a new work of historical fiction, King of Kings, about King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. His latest book, Villainy Ever After (2022), is a collection of classic fairy tales told from the point of view of the villains. Jason is a member of the New England Indie Authors Collective and holds a BA in Journalism from the University of Massachusetts Amherst. jasonmrubin.com.