Visual Arts Review: Is There a Boston Art?

By Helen Miller and Michael Strand

Arnold Trachtman, Isabelle Higgins, and Barbara Ishikura are all “Boston Modern” artists who never stray far from communicating all-too-human joys and worries.

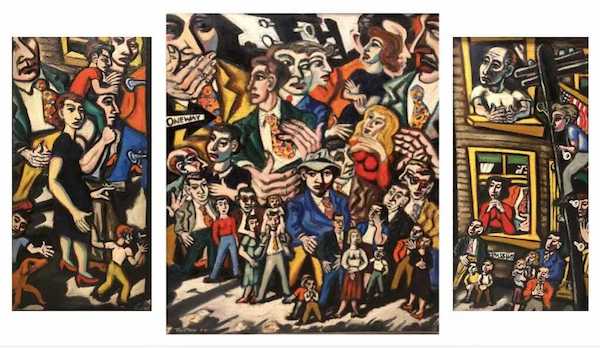

Arnold Trachtman, The Watchers (1961). Photo: courtesy of Childs Gallery

On the Town, at Childs Gallery (through March 11), features a selection of Boston-based artist Arnold Trachtman’s cityscapes and group portraits. The artist, who passed away in 2019, had a long career and had many ties to the area, so the show offered an invitation to explore the movements in which he may have played a part. Fortuitously, Between You and Me at LaMontagne Gallery in SoWa on the South End (through March 25), which showcases the portraiture of contemporary Boston artists Isabelle Higgins and Barbara Ishikura, aided and enriched that quest.

At first glance, these two shows might seem to have little in common. Nonetheless, the work in both somehow feels very “Boston” and that distinctive look fed our curiosity: What is the legacy of this colorful, blunt, woozy, representational painting, a kind of neo-expressionism, which keeps bubbling up? Associations that immediately come to mind include social realism, Mexican mural painting, German expressionism, cubism, Courbet, Manet, Kahlo, and art deco, with its mix of modern and classical. The paintings of Trachtman, Higgins, and Ishikura are nothing if not stylized. But this does not mean they are any less connected to a tradition that is recognizably local in both form and content.

In one sense, the local connection is institutional. The Massachusetts College of Art and Design serves as a conduit for Trachtman, Ishikura, and Higgins alike—they were all educated there. Ishikura and Higgins now teach there, and Trachtman taught at MassArt starting in 1982. This is relevant to their work’s vernacular, and it may reflect the prominent place of illustration at the school today. But to probe our initial impressions, which are related to painting specifically, we need more. A long time visitor to Boston art, Philip Guston, is helpful for lending further perspective; after all, he rediscovered figurative art while lecturing at the Boston University School of Fine Art in the late ’60s and through the ’70s. We wonder whether the city may have been essential to Guston’s paradigm shift. Maybe he had to come to Boston to fully realize the potential of the figure for his work; the stakes of abandoning abstraction were simply too high everywhere else.

With the delayed exhibition Philip Guston Now open last May, we cannot help but see Higgins and Ishikura’s recent paintings in relation to Guston’s work. In Our Christmas Card (2022) and Sins Paid in Full (2022), for example, Higgins portrays herself and her partner in bed—a place where many of Guston’s late portraits of himself and his wife take place—each hair on their naked legs a separate brushstroke. The outsized, cartoonish hands and feet of Ishikura’s otherwise elegant subjects in paintings like Rebecca on Floral Chairs (2023) and Nancy on a Plaid Blanket (2023) remind us of Guston’s blocky shoes, a marker of the artist’s newfound freedom from abstract expressionism. His evolution involved mundane, often self-deprecating motifs and poignant historical commentary. Ishikura’s freedom seems to lie in the option to take her shoes off, literally, along with other liberated women in her life.

Guston influenced a generation of Boston-area painters, many of whom studied with him at BU, or next door at the Museum School. Yet before Guston entered the Boston scene, other influential painters made their way, or spent some part of their exile, in the city, like the German artists Max Beckmann and Karl Zerbe. It is not hard to see the characters, trumpets, and green shadows in Beckmann’s famous Family Picture (1920) or Carnival (1920) echoed in Trachtman’s Kinder Spiel (Children’s Game) (1961) and Parade (1960), included in the Childs’ show. The interest in harlequins and the sinister runs deep. Zerbe, meanwhile, remained in the city, became a US citizen, and led the painting department at the Museum School (now affiliated with Tufts) through mid-century. He taught figurative art to, among others, David Aronson, who recruited Guston to teach at BU.

But even accounting for Guston, and his welcome reception by faculty and students, something is still missing. If Guston found a home in Boston, it may have been because the city itself was, in a sense, prepared to receive him and embrace his figurative turn. Boston-bred artists Hyman Bloom and Jack Levine both learned to paint in a settlement house and later with the Harvard professor Denman Ross.It appears they both arrived at an almost corporeal expressionist style, bold and adaptable enough to adequately confront the prejudice and insecurity experienced by Jewish immigrants to the city, and even the violence of the Second World War, foreseen by Beckmann in Hölle der Vögel (Birds’ Hell) (1938), a sardonic but ferocious condemnation. The expression of such inhumanity reverberates in the most dark and daring, if not the most widely exhibited or popular, of Trachtman’s work. Bloom and Levine themselves put paint to canvas in a shockingly expressive way for city patrons accustomed to the virtuoso surfaces of John Singer Sargent or the glittering brushwork of Childe Hassam’s American impressionism, set in drawing rooms or overlooking the golf course. The work was modernist, and Bloom and Levine would later join Zerbe in the Modern Artists Group of Boston, where Beckmann lectured.

Jack Levine, Street Scene No. 1 (1938).

In Bloom’s The Synagogue (1940), a vivid and crowded synagogue is captured from above and below simultaneously—bright chandeliers, on the one hand, and shadowy steps on the other, taking up two thirds of the composition. Rabbinical figures in the middle ground of the painting are flanked by adolescent boys and young men, their heads tilted back in song and prayer, their mouths wide open like baby birds. The image depicts an intense and, it has been noted by critics, defiant spirituality. Levine’s Street Scene No. 1 (1938) employs a similar palette of red, white, black, and gold in an image that reflects ordinary life in a Jewish community. The ruddy flesh tones of its store managers stand out above their crisp main-tailored shirts. A customer waits patiently, while the city appears distant, caught in the upper left corner of the background. The picture presents a mysteriously layered, even sullied view, the entire composition jarringly aslant.

Trachtman, who was also Jewish but a generation younger than Bloom and Levine, offers another scene of Judaism in Boston at the Childs Gallery exhibition. In his study for Mr. Tillson Makes His Way Through The Brickyard (Lynn, MA) (c. mid-century), Trachtman harkens back to Levine in terms of content and style, transforming what might otherwise be a straightforward scene of an orthodox elder’s daily walk, forcing us to accept a new perspective as the painting bends its way around a host of younger figures.

In Trachtman, we can see how figurative painting survived in the city. The Watchers triptych (1961), a highlight of the Childs’ show, harnesses Beckmann, defining the mood and movement of each individual in relation to a scene of dramatic commotion. The repetition and differentiation of boldly delineated hands and profiles are particularly emotive, well-observed, and purposeful. Trachtman is most known for his politically informed work, his Vietnam-era protest paintings, chilling satire of the Reagan presidency, and portraits of left-wing idols like Bertolt Brecht. Dana Chandler, a next generation artist from Roxbury credited with directing attention to Black artists and communities through art, murals, and fearless engagement with local museums, is not infrequently paired with Trachtman; both lent the tools of expressionism to a politically engaged, topical art. While the works in On the Town may appear toned-down by comparison, they are not any less rooted in social critique fitting for the time.

Central Square (1967) is a large acrylic painting that presents a slick, multi-perspectival urbanscape of the famous junction in Cambridge. The mood, on first impression, is light, an everyday medley of baby blue and sunshine yellow, coupled with the clean lines of pictograms and street signs. Focusing on the intersection, however, we are soon overwhelmed by corporate logos and ads, the signifiers of a consumerist machine. Trachtman stencils the people in with such sensitivity that even from the back, at a minor scale, their posture and personality shine through—in the way a man’s jeans hug his calves, or two people walk and talk, gesturing to get their ideas across. He does not let these figures disappear into the background.

These traits—humanism, the use of multiple perspectives, vibrant colors and shapes—remain loyal to a distinctly expressionist heritage. The satire and critique also share in the spirit of Levine’s Feast of Pure Reason (1937), in which a capitalist, a police officer, and a city politician scheme, flush with food and drink. Both Trachtman and Levine suggest grotesque malice behind the scenes.

Arnold Trachtman, Charles River (1966). Photo: courtesy of Childs Gallery

Even Trachtman’s view of the serene and picturesque Charles River (1966) encodes the suspicions. The central Boston cityscape of yesteryear (pre-Hancock, we might say) comes alive from the Boston University Bridge through a fish-eye lens, in which many perspectives are highlighted as well as resolved. We step into the horizon line and look down at the common summertime scene of sailboats on the Charles. Looming over Beacon Hill are the new (at that time) West End high rises. The Custom House from 1915 pops up behind the golden dome of Bulfinch’s State House from 1798, alongside the Pemberton Square redevelopment of the early ’60s. On the far right we find the newly constructed Prudential Tower from 1964. Trachtman depicts Boston after one of its many facelifts. The buildings arise seemingly out of nowhere, like aloof monster chess pieces. The abrasive architectural mix seems to signal how the olde towne is constantly being reshaped, hinting, perhaps, at the presence of undemocratic undercurrents, powered by the wheeling and dealing of the power elite Levine satirizes.

Turning to Higgins and Ishikura, it is easy to see the individuals and couples in Higgins’ drawings and paintings hunkering down inside apartments on the edge of Trachtman’s burgeoning city center. In their domestic scenes, Higgins and Ishikura portray people dwelling in communities around the city today. In this way, they carry on the earlier documentation of city life undertaken by Levine and Bloom. Higgins portrays Boston some decades after Trachtman: she finds it in a state of late-capitalist deterioration—a city of expensive, cramped apartments and substandard services. In Sins Paid in Full (2022), a couple sleeps together on a too-small bed in a room of exposed brick and pinewood floors, uncovered by blankets. An unplugged window fan suggests the heat of summer sans air conditioning. In Never Ending (2022), Higgins covers her head as water rains down from the dropped ceiling.

Higgins’ portrait scenes take place almost exclusively at night, and indoors, often in a sea of phthalo blue punctuated by orange and neo-fauvist color schemes. They suggest an Edward Hopper kind of loneliness, though its causes are more explicitly sinister than those found in Hopper. For example, there are such self-portrait titles as I Can’t Flirt, I’m Thinking about Caskets (2021). Here, the subject’s watery wide eyes stare up at the viewer above a table covered in take-out chicken legs and bones, car keys, a can of Corona, and a spilt bottle. The Allston donut shop out the window is matched by a disintegrating map of the United States. We find ourselves, alone with Higgins, mourning national disasters.

Still, many of her paintings feature a benevolent spirit who accompanies the artist and other characters as they dream and worry about the future. Starred sequins are a frequent motif, as is a sense of resilience. The artist often sprinkles her paintings with small items scattered about the space. In Roost (2022), a 30” x 32” oil painting, the scene is set by a background of what looks like tree trunks and a brilliant aurora. A young woman’s dream-furrowed face turns towards a small nest of light green eggs in her open hand. This posture at least temporarily tips the scales—on the other side of the bed a dark purple ashtray holds a half-smoked cigarette.

Isabelle Higgins, October 1st, 2021 (2023). Photo: courtesy of LaMontagne Gallery

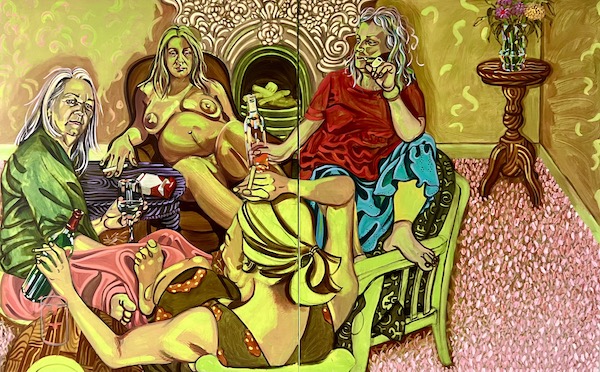

Smoking and its iconography make a frequent appearance in Between You and Me, most notably in the two largest oil paintings in the show. They are powerfully installed on adjacent walls: Four Women and Pink Shag (2023), a 60” x 96” diptych by Ishikura, and October 1st, 2021 (2023), Higgins’ table-sized 72” x 48” showpiece. Painting, Smoking, Eating (1972), perhaps Guston’s most well-known autobiographical work, may be an influence here. Not one but two cigarettes dangle from Ishikura’s outstretched arms. She hasn’t had a chance to smoke them yet because she is having so much fun. Higgins’ still life vocabulary reflects Guston’s pathos; in contrast, Ishikura’s subjects appear to revel in the freedom to smoke and drink “like a man.” One of the four women in Ishikura’s diptych even has her shirt off! In fact, she’s completely naked, as are so many women in the history of painting. And pregnant, as are so many of the painter Alice Neel’s subjects, in her signature bold outlines. Left of center, the woman’s bedroom eyes suggest the hormonal roller coaster careening inside. Meanwhile, she has no shame and smokes along with the rest of them. To her left, the self-assured, if more reserved and sensitive of the bunch—perhaps mildly concerned grandmother-to-be—resembles Jamie Lee Curtis in any number of “strong female roles.”

The group of friends that Higgins has over for noodles, cake, and cherry pie to celebrate her 25th birthday captures a moment not uncommon in the 6th most diverse city in the US. It could be their age, not to mention the pandemic, but the friends ringed around the table appear less comfortable than the women in Ishikura’s fire-lit living room, who could have been lifted from La Danse (1920) by Henri Matisse, or David Hockney’s remake, The Dancers V (2014). (The first in Hockney’s series — The Dancers I [2014], in which the group stands holding hands though they have yet to acclimate to one another or the artist’s jubilant idea for the work—could be a model for Higgins’ group.) Many 20 and 30 somethings in Boston live in rented spaces that are becoming increasingly expensive with each passing year in a city without rent control. A pack of Marlboro’s joins other exquisitely rendered still life moments, as in Ishikura’s painting. One guest smokes and smiles, others look down or sideways sheepishly. The black grid of the blue tablecloth echoes the chain link fence in the background.

Barbara Ishikura, Four Women and Pink Shag (2023). Photo: courtesy of LaMontagne Gallery

Patterns and vividly painted fabrics are a hallmark of both contemporary artists’ work. They seem to celebrate the confidence that can come with age and affluence—and feminism—in Ishikura’s world. They play a more somber note in Higgins. In Rebecca on Floral Chairs (2023), Ishikura paints a woman lounging/posing in a brilliant gold dress—it is so dense it could have been carved out of marble. This dress resonates with the fireplace mantle and other classical features of the furniture in Ishikura’s paintings (and the goddess-like neoclassical figures in murals Guston painted for the Works Progress Administration [WPA] in the ’30s and ’40s). The woman is not intimidated by her outfit; she wears the dress with vibrant ease. Facial expressions in Ishikura’s paintings are captured so successfully that we feel as if we’re right there with them in the illuminated yellow-and-pink rooms. And it is a varied bunch: people at various stages of life, appearing more or less content.

According to the art historian Judith Bookbinder, “Boston Modern” is a kind of figurative expressionism that stands against abstract expressionism and subsequent movements intimately tied to New York. In the opinion of many critics, even today this local tradition remains little understood, seldom acknowledged, and dramatically undervalued. Discerning influences is a mysterious and complicated matter, but Trachtman, Higgins, and Ishikura embrace an emotional directness, as well as a consciousness of broader social circumstances, that link them to earlier city painters such as Bloom and Levine. Critique and satire have their place, but these Boston artists forgo ambiguity and irony. The city gives this art license and nourishment and provides it with a home. In all cases, form serves lived experience. These artists never stray from communicating all-too-human joys and worries.

Helen Miller is an artist. She teaches at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and Harvard Summer School. Michael Strand is a professor in Sociology at Brandeis University.

Tagged: Arnold Trachtman, Barbara Ishikura, Boston Expressionism, Boston Modern, Child’s Gallery, Helen Miller, Isabelle Higgins, Michael Strand

Figuration has been a defining characteristic of the fine arts of Boston. During the WPA years there was a transition from the genteel Brahman impressionists, embraced shown and collected by the conservative MFA, to the brash social justice infused Boston expressionists. Recognition of these artists has been a long slow process including a major Hyman Bloom show several years ago at the museum. The Danforth Museum has embraced figuration in Boston. During a long and vibrant career Arnold Trachtman was marginalized by mainstream curators and critics. I knew him well curating the work into shows and writing about it. He continues to be ignored by the MFA although the deCordova owns a major work. The Guston influence is elaborate and complex. The MFA declined an intended gift by the artist which decades later participated in a traveling exhibition. It was good to read this piece by a new generation of critics.