Book Review: “Epic Annette” — What is Heroism?

By Kai Maristed

Surely the selfless subject of Anne Weber’s Epic Annette qualifies beyond doubt as a true heroine of the twentieth century?

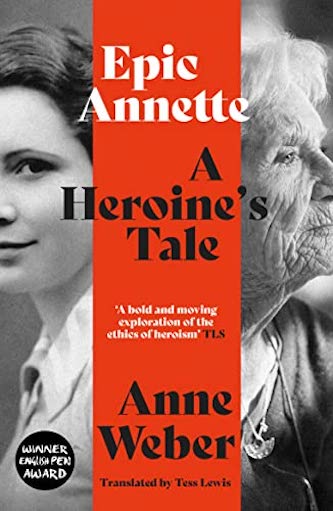

Epic Annette: A Heroine’s Tale by Anne Weber. Translated from German by Tess Lewis. Indigo Press, 181 pages, £11.99.

Some people experience more lives in one mortal span than others can imagine — or would want. Take Annette Beaumanoir, who was an active woman in her nineties as this eponymous book took shape. Born in poverty in Brittany, she volunteered as a teenager for the underground French Resistance, was twice married, mother of three, a highly respected MD researcher in neurology. Then, as an ‘illegal’ courier, she risked death yet again for the ‘Free Algeria’ FLN. She was condemned to a ten year prison term, escaped, and worked as an advisor in the Ministry of Health of a newborn, ravaged North African country. Surely the selfless subject of Anne Weber’s Epic Annette qualifies beyond doubt as a true heroine of the twentieth century? Indeed, ‘A Heroine’s Tale’ is the subtitle, echoing the German original title: Heldinnenepos.

Some people experience more lives in one mortal span than others can imagine — or would want. Take Annette Beaumanoir, who was an active woman in her nineties as this eponymous book took shape. Born in poverty in Brittany, she volunteered as a teenager for the underground French Resistance, was twice married, mother of three, a highly respected MD researcher in neurology. Then, as an ‘illegal’ courier, she risked death yet again for the ‘Free Algeria’ FLN. She was condemned to a ten year prison term, escaped, and worked as an advisor in the Ministry of Health of a newborn, ravaged North African country. Surely the selfless subject of Anne Weber’s Epic Annette qualifies beyond doubt as a true heroine of the twentieth century? Indeed, ‘A Heroine’s Tale’ is the subtitle, echoing the German original title: Heldinnenepos.

Epos denotes a poetic form, whereas in English ‘epic’ equally suggests outstanding size or grandeur. Weber’s book aspires to be the literal thing: a 204 page epic poem composed of verse units that don’t on average exceed twenty-five lines. Reader, do not let a matter of form put you off! To be honest, the author’s free verse is to my ear (thank you, German Audible) indistinguishable from prose, and Tess Lewis’s translation is both pitch-perfect and exact. The voice of Epic Annette rolls through history as a jaw-dropping contemporary adventure tale, now high-flown, now colloquial, with plenty of off-stage commentary from the omniscient narrator — she is unnamed and indistinct, like a Greek chorus, yet a character in this tale. Turns out to be an investigator at times. Even a judge.

Why then, this choice of ‘epic poem?’ My guess is that Weber found it gave her project the needed freedom to dive in and pull out quickly, to convey a dramatic scene in one paragraph, then zoom out, Homeric-style, for a panoramic view of matters unknown to her subject, or for a swift swipe forward or back in time.

Does the opening paragraph above, which lists high points of Annette’s career, constitute a spoiler? No, because Epic Annette convinces as a tale of extraordinary idealistic courage and self-sacrifice through its quotidian detail. The child’s guiding lights are a loving mother and father, both quick to aid anyone in need or downtrodden, despite their own poverty in a small fishing village. Born firebrands for justice. And above all her adored grandmother, Mamère, raised essentially in serfdom, sleeping on straw, allotted wooden sabots but no underwear.

At sixteen, under the Nazi Occupation, Annette’s ardent thirst for action isn’t slaked by occasional contraband deliveries and hand-offs. In Paris, at University, she passes through the disorganized Trotskyites to a possible real entry to the Resistance.

‘Paris is big! Paris is small. Tiny in fact,

if you only count those who refuse to fall into step with the Germans

…you have to want to find them and know how.

‘… He who fishes shall find!

She’s met one of them previously and he

puts her in touch with a potential contact. Chance or destiny leaves

very little margin for error…

She will see her contact leaning on the railing,

immersed in a book, and clamped under his right arm,

Signal—not the brand of toothpaste we have today,

but a propaganda journal spreading Nazi ideology

in the occupied countries of Europe. She is to say—’

Success. And so the first real adventure begins, leading her into the rigorous discipline of the Communist Party, and later, for painfully good reasons, out again… but now there is a risk of my telling too much. So be it: I can’t resist adding that not yet aged twenty, in the vengeful lynch-happy fury that followed the German defeat, short and chubby-cheeked Annette is appointed with six older men to triage among those accused of having been collaborationists. The probable traitors here, there are the average cowards, and those simply fingered out of jealousy or greed. At this point the narrator pulls back, to inform us that: “During the Occupation and shortly after, eight thousand men and women are summarily liquidated. Fewer than eight hundred are executed after being tried in court.’

Historical asides like this one, stunning at least to this reader, provide more than enrichment; they expand the biography of an extraordinary individual into an expressionist portrait of a swath of one European century. When Annette’s fervor turns to supporting the rebel FLN, we hear again DeGaulle’s duplicity in his famous statement in Algiers in 1958 — I have understood you! — although the government had no intent of granting independence, and suspected rebels were being tortured

‘…in the domestic intelligence agency, the DST,

at 11 rue des Saussaies, the building that housed

the Gestapo’s headquarters fifteen years before.’

Generally, in this short book Weber paints a more nuanced and chilling picture of the factional wars within the FLN, vis-à-vis its Tunisian hosts, and against France than you’ll find in many history texts. One learns, for example, that Adenauer’s Germany covertly supported the FLN. Again, a body count:

‘It took eight years of war and roughly

five thousand dead, most of whom,

around four thousand five hundred, were Algerians…’

And what of Annette’s personal losses, as the century enters its fourth quarter? Her loves. Her children, grown to strangers. Slipped away or torn away, in the end sacrificed to her ‘inborn’ idealism and her socialist democratic hope for humanity’s future. Perhaps also (yes, she comes to interrogate herself so) to satisfy a more selfish craving. Like a soldier who re-ups for the next war and the next, did she become increasingly addicted to the threat and thrill of danger, the soul-affirming tests of hardship? Anonymity, prison, revilement, exile. Was she naïve? Outraged by France’s crimes toward its colonies, but blind far too long to the incursions of Islam into the once-secular FLN, and the bloody struggles there that boiled down to greed and power-grabbing — and led to what has essentially been a dictatorship ever since. Loss of her self-defining ideals? Loss of hope?

Author Anne Weber.

These are the kind of questions Weber asks with increasing urgency as she leads us down Annette’s road. Repeatedly Annette struggles when faced with violence and injustice on the side she supports, with the problem of means versus ends. The moral inquiries occasionally become repetitious, along with the ‘what if she had known,’ asides, and can veer into moralizing territory. However rhetorical and unanswerable, they all point to one overriding question, whether intended or not: what is heroism? Fact, or romantic illusion? And either way, was Annette Beaumanoir a heroine? In the explosive light of this year’s Russo-Ukrainian war, there is nothing outmoded or childish about asking: what, if anything, makes someone a hero.

Based on Annette’s own published memoir, as well as extensive personal interviews, Weber’s book ends abruptly, with the exhausted protagonist’s return from working as a stranger in an increasingly alien land to France, unaware that decades of life still lie before her. No surprise that mentions of the Odyssey punctuate Epic Annette, along with references to the Algerian-born firm pacifist Albert Camus as well as fellow-traveling revolutionary André Malraux (who does not come off too well.) Fittingly, though, the classical image Weber closes with is not that of the lost, questing sailor, but of Sisyphus, leaning forever into his boulder, as seen through Camus’ compassionate eyes.

Kai Maristed studied political philosophy in Germany, and now lives in Paris and Massachusetts. She has reviewed for the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times, and other papers. Her books include the short story collection Belong to Me, and Broken Ground, set in Berlin. Recent work includes “Evangeline, or Theories of Childhood Development,” in the Iowa Review, “The Age of Migration,” in Ploughshares, and a forthcoming essay in Agni. Read Kai’s Paris-centric take on politics and the arts here.