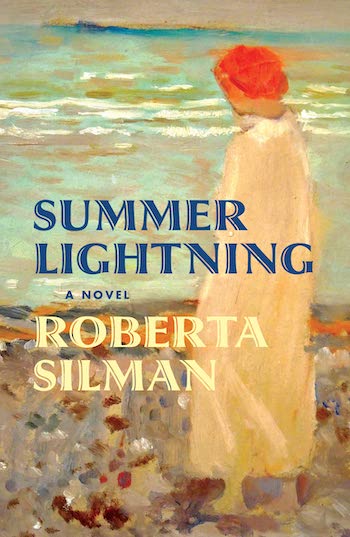

Book Feature: An Excerpt From Roberta Silman’s “Summer Lightning”

As Spring approaches, a treat. An excerpt from Summer Lightning, the latest novel by Arts Fuse critic Roberta Silman. It is a book that attempts to convey happiness.

Author Roberta Silman. Courtesy of the artist

Summer Lightning is my fifth novel and tells the story of the Kaplow family, starting with the encounter of two strangers at Roosevelt Field where Lindbergh embarks on his famous flight in 1927 and ends in 1966, almost 40 years later. This is the journey of an ordinary family negotiating the extraordinary events of the 20th century, starting with Isaac’s immigration from Eastern Europe to Manhattan and ending with the death in 1966 of a famous poet whom his wife Belle has befriended. Through the Depression, the Second World War, the McCarthy era, the Kennedy assassination, and the fight for civil rights.

After writing Secrets and Shadows (2018) which had some harrowing parts about a family being hidden in Germany during World War II, I decided I wanted to write about a normal family, if there is such a thing. I had always been struck by Osip Mandelstam’s line “How poor is the language of happiness.” In other words, how hard it is to convey happiness. But I wanted to try. So this is a book that affirms life, a book that would show that not all of life is struggle and doom. A book about connections and how one maneuvers through life strengthening or breaking those connections. And when Belle gets to know Larry Rivers and his friends it also becomes a book about who is an artist and who is not, and the place of art in all our lives. Lastly, it is a book about race: how this liberal family meets a challenge to their ideals when the younger daughter falls in love with a Black man.

So we have a novel that charts a family’s trajectory over 40 years buffeted by public events over which they have no control, but who can remain true to their principles as they figure out their private lives with as much grace and dignity as they can muster. As one reviewer said: “[A book] about the value of caring for others regardless of social or racial, or ethnic differences, though their commitment to equality will be tested by Vivie, the youngest, in the Civil Rights era…. What will resonate most with readers is Silman’s intensely emotional depiction of the Kaplow’s commitment to family and helping others. Silman portrays the Kaplows as genuine people who manage to instill true integrity in their children.” If fiction is the history of the world, as I believe it is, this seems a worthy goal to attain while writing it.

— Roberta Silman

(Editor’s Note: Roberta Silman will be interviewed by Matthew Tannenbaum of The Bookstore in Lenox at The Mount in Lenox on June 9 at 5 p.m)

The following excerpt is from pages 200 through 207, when Vivie is going to Oxford for a summer fellowship after graduating from Radcliffe and meets Herbert Johnson.

JUNE 1963

“You know,” Isaac said while they were waiting at Idlewild, “I’ve always loved the idea of flying, that’s why I went to see Lindbergh take off in 1927. And the funny thing is that I’m never scared, even when the weather is bad. Because whatever happens is out of my control. So it becomes a strange kind of release, a release so complete that I suppose it’s happiness.” He looked sheepish.“It sounds trite, but there it is.”

It didn’t seem trite, it made sense. Her father loved his life—he loved her mother and her and Sophy and Michael and Rosy, he loved his parents and his brothers and his business, and their synagogue, and Jules, and a score of others. Yet now Vivie understood that even her stalwart, inquisitive, optimistic father sometimes needed a respite from his doubts and responsibilities. That soaring above the earth was beyond his wildest dreams, something out of Jules Verne and H. G. Wells. If he could fly, anything might be possible for his children, for the world.

That sense of possibility was why he came to America, why he listened harder than anyone she had ever known, why he responded so fully to what was new, like Sputnik. Unlike those who felt that space travel rendered Earth and all on it insignificant, Isaac was thrilled by it. “There may be millions of people out there as intelligent or more intelligent than we are, as curious about us as we are about them. What could be more amazing?” he would ask.

So as he held her close to say goodbye, his eyes commanded, Fly, Vivie, and learn what it is to be free.

She stepped onto the plane excited and expectant. Soon, though, she became disoriented and dizzy as the fields and roads and cars and houses receded to specks and then were obliterated by clouds. Not very much to hang onto. So she took a deep breath—relieved beyond description when they landed in Gander to refuel—as she stepped into the most radiant dawn she had ever seen. Inhaling the crisp air she pulled her sweater around her, consoled by the strange sensation in her feet, as if she’d just shed ice skates for shoes.

But as they soared over the Atlantic once more, she became rigid with fear. Such a vast expanse of shirred ocean! Would it ever end? How blithely she had told people about this trip: “A propeller plane and it takes almost twenty hours.” Belle had brought her hand to her mouth but had not said a word. Thinking, Vivie knew, of the shocking plane crash that had killed Patsy Cline in March. At thirty-one. But that had been a private plane; this was a commercial aircraft.

The fear and isolation Vivie now felt reminded her of a time when there were muffled voices and a thick coral hand passing before her eyes, then those same hands unwrapping her, as if she were a package, and finally frantic brown eyes peering, searching. For what? “That’s Carrie,” Sophy told her when she first described it. “Making sure you could see, the night a pot of cereal fell on your head. But I can’t believe you remember it, you were so small, they say memory doesn’t start that young.” Yet here it was, assailing her as it always did when she felt she was in trouble.

How could that be? She was twenty-one years old and on a plane to England to spend six weeks at St. Hilda’s College at Oxford where she’d been awarded a summer fellowship to study literature and art. A new beginning. Yet at this moment she was mired in the past. Where did this feeling of living through certain moments in her life at the same time come from? What did it mean? She’d had hints of it before, but now it was more powerful. Was this why her father loved to fly? Because here, in this manmade bird whizzing through the sky you could erase time and let all these moments fully enter your consciousness?

Finally, though, she had to stretch. On her way to the bathroom she saw a knife glittering in the aisle and when she bent to pick it up, she saw a brown forearm. A man was writing in an artist’s sketchbook. She knew she should stop staring, but the moment she saw that brown arm she felt less tired and less afraid because it brought back those hands that held her, cosseted her, dressed her, brushed her hair, fed her, and once, only once, raised a quivering pink palm to hit her after she confessed she’d stolen some cherries from the greengrocer’s stand. Then the hand stopped mid-air and pulled her so close it seemed Carrie wanted to pull Vivie into her very skin and bones. As the past unfurled so quickly in her mind, Vivie stifled a wild urge to reach out and touch the man’s arm. But common sense prevailed; slowly she made her way to the cramped bathroom and back to her seat.

Several hours later, though, he was standing in the Gatwick Immigration Office among the crowd of college kids like her, some older tourists, and a few families. Their exhilaration at having landed now faded as they were subjected to the usual polite, British nonsense: immigration officers with a pathological obsession for detail that masked a real, though suppressed, fright about who wanted to enter their beloved England.

Vivie’s gaze was riveted by an Indian mother who kept pulling on her sari to cover that small spot on her midriff usually left bare. As Vivie watched the woman’s fingers creep along the edge of her clothing she wondered what these proper Englishmen would do with the Puerto Ricans now flooding Manhattan? She shrugged and found a seat; if she could sleep maybe she wouldn’t feel as though she were pushing her limbs through sand.

As she was coming out of her initial doze, he was writing again. Only one empty seat separated them. How could he have the energy after such a long flight?

“Would you like to use my pen?” His teeth were even and white against his purplish lips, his eyes amused. She shook her head and gave him a small smile, too embarrassed to speak. “Embarrassed?” she could hear Sophy ask. “You, embarrassed?” But she was. Perhaps because she was so tired or perhaps because she so desperately craved human contact after the harrowing plane ride. Soon her name was called. She went through the queue and lost sight of him.

Yet one day not more than a week later, there he was. A splendid day when the leaden thickness that was simply English air had, miraculously, lifted. As she walked over Magdalen Bridge into the deer park, their eyes met, as skittish as the animals grazing around them. He gave her a pleasant, good day smile. Her hand fiddled with her collar as he passed.

“Someone you know?” the young woman with her asked.

“Yes. No. No. We came over on the same plane.” As his tall figure receded she longed to know his name.

At the beginning of July there was a short break wrapped around a weekend. A group of students who were reading Baudelaire in French decided to go to Paris, a boat trip from Southampton to Le Havre, a few hours travel each way. When she went below deck for a cup of tea, he was writing even more furiously than before.

Vivie sat there, unable to believe her eyes, but feeling more like her usual self: the vibrant young woman whose reddish hair made her feel not only blessed but bold when she wanted something. And what she now wanted was to tell this handsome man that he evoked a flood of precious memories, that he didn’t need to be so stand-offish, that she didn’t even need to know his name. Only that the sight of him made her feel as if she’d hiked miles in an English drizzle and was finally warming herself before a blazing fire, then settling into a sofa whose worn upholstery had acquired a sheen of unexpected beauty in the reflected firelight.

That was all.

But if you want to tell someone that much, it can never be all. “You’ve got a different pen,” she began. He raised his eyebrows.

“We’ve met, in Immigration at Gatwick and then in the deer park.”

His silence was unnerving. And no answer, just that disinterested look, as if he were watching a fly land on his arm. If he had responded eagerly, it would have ended. Vivie didn’t bother with people who were friendly. But he didn’t know that.

The facts, which she learned later, were that his aloofness was a ruse. He knew her name. Everyone knew her name. She was the tallest woman at the Oxford summer school. “The smashing redhead at St. Hilda’s just graduated from Radcliffe. She’s as smart as she is good-looking, and her name is Vivienne Kaplow,” an American named Ernie announced.

“That’s a mouthful,” someone said. The Americans stared and the speaker looked around nervously. “I mean … ” They knew what he meant. And now she was standing in front of him, trying to strike up a conversation.

All at once a frown, like a cloud racing across the sun, blurred his features. She waited for him to say something, but he just shrugged, then his hands whipped the air as he picked up his notebook and bent his head to read what he’d written.

“I’m not going to bite.”

His head snapped up.“People think you’re Australian, but I remember you from the plane,” he blurted.

She waited. Now that she had his attention, there was no need to rush. And she knew what he had just told her. Her good ear had picked up a slight English accent, so people stared and said, “So you’re Aussie, are you?” then registered surprise that she was American. Just enough to confuse, as she was confusing him now. But he clammed up and averted his eyes.

“You don’t have to be rude, it’s very bad form to be rude to a fellow American. After all, we’re in this together.” Then she blurted,“Isn’t it awful?”

“Oxford?” His voice was low.

“No, Oxford’s wonderful. I guess I don’t mean it, I think I mean they. The people, so stiff upper lip, so controlled, so polite. But anti-Semitic. Whenever I tell someone my name they begin the next sentence with, ‘You people,’ as if they’d never seen a Jew before, but there are lots of Jews here, aren’t there?” Now her voice didn’t sound so sure, or so English.

“I don’t think they’re especially anti-Semitic, they just aren’t crazy about anyone who isn’t English. They’re not fond of the French or the Italians and they hate the Germans. A friend of mine says they’re miserable because all their favorite spots in Spain and Italy are crawling with Germans.” He paused. “And they sure aren’t fond of people like me.”

Vivie nodded. “I’ve heard that. About the Germans.” Now it was her turn to pause.“But they have every right to hate the Germans.” She frowned.“And they’re basically kind. Maybe it’s not the people, maybe it’s the food. I can hardly eat anything, it looks and tastes so … so tapioca. It makes me gag.”

Finally he laughed, but after a moment retreated again. Well, she decided, I’ll give it one more try. She rose and took a step forward, then said, “No white girls, they told you not to mess with white girls, didn’t they? Your mother and sisters. White men are fine, they can teach you what you need to know, but white girls are trouble, right?”

“Where did you learn to talk like that, how do you know ‘Colored talk’?” Finally he made a gesture of surrender, palms facing her.

Vivie’s knees turned to rubber. Until now this had been a game, the kind of behavior that used to make Sophy snap, “Stop amusing yourself with other people.” Or made her mother say, “Sarah Bernhardt, playing to the gallery.” Or caused Carrie to remind her,“You are not the belly button of the universe.” Though she pretended to take them seriously, Vivie never truly felt shame. No, all that mattered was to have all eyes on her.

Suddenly, though, she knew she’d gone too far. As soon as she saw his poignant gesture of defeat, she knew she should retreat. But she couldn’t. With that innocent sign he had let her into his life and had also transported her thousands of miles back home. Now, maybe for the first time since she went off to Radcliffe, she could talk about things that had been stuck in her throat for too long. How furious she was at her parents—the same parents she loved so much that most people thought she and Sophy were off their heads—because they sold the house without even consulting her, and how sad she was that Michael and Sophy were going off to live in London.

“Be yourself,” her father told them. “To thine own self be true.” As if that were really possible. “No pretense, they have no pretense,” her parents would bestow their highest praise on someone. Vivie heard and never understood. She seemed to be all pretense—inventing, embroidering, embellishing, entertaining, flirting until she hardly knew who she was.

Yet now all such compulsions had vanished. All the need for attention was gone. It was enough just to be.

There was so much she wanted to tell this man whose skin smoldered and whose teeth flashed as he smiled. He seemed to know what she was thinking although she had not uttered a word. He laced his fingers together and his eyes met hers. I’m listening, they said.

Slowly Vivie cleared her throat, “I hardly know how to begin.” But then she felt his feathery touch on her arm. Silently, he propelled her towards the railing, and there, spread before them was the busy harbor of Le Havre. A feast of color for their hungry eyes.

Roberta Silman is the author of five novels, a short story collection and two children’s books. Her latest, Summer Lightning, has been released as a paperback, an ebook, and an audio book. Secrets and Shadows (Arts Fuse review), is in its second printing. Both are available on Amazon. It was chosen as one of the best Indie Books of 2018 by Kirkus and it is now available as an audio book from Alison Larkin Presents. A recipient of Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has reviewed for the New York Times and Boston Globe, and writes regularly for the Arts Fuse. More about her can be found at robertasilman.com and she can also be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.