Opera Album Review: A Marvelous New Recording of Rossini’s “The Silken Ladder”– at a Bargain Price

By Ralph P. Locke

Rossini’s one-act opera from 1812 rings fresh changes on a host of comic-opera clichés.

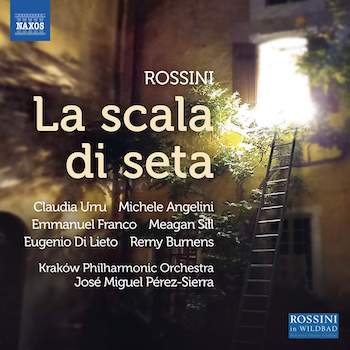

ROSSINI: La scala di Seta

Claudia Urru (Giulia), Meagan Sill (Lucilla), Remy Burnens (Dorvil), Michele Angelini (Dormont), Emmanuel Franco (Germano), Eugenio Di Lieto (Blansac).

Kraków Philharmonic, cond. José Miguel Pérez-Sierra

Naxos 8.660512-13 [2 CDs] 88 minutes

If you wish to purchase the CD set (from the inexpensive label Naxos) or hear the beginning of each track, click here. The entire recording can be heard on Spotify and other streaming services.

Remember the wooden ladder in The Barber of Seville? Figaro sets it in place under Rosina’s window so that she and Count Almaviva can elope. By contrast, a “scala di seta” is a ladder made of silken cloth. The advantage, presumably, is that, rolled up, it can look utterly innocent on a shelf in a young woman’s bedroom.

Remember the wooden ladder in The Barber of Seville? Figaro sets it in place under Rosina’s window so that she and Count Almaviva can elope. By contrast, a “scala di seta” is a ladder made of silken cloth. The advantage, presumably, is that, rolled up, it can look utterly innocent on a shelf in a young woman’s bedroom.

In Rossini’s The Silken Ladder, the heroine, Giulia, has regularly unfurled the cloth ladder from her window so that she can enjoy nightly conjugal visits from her beloved Dorvil, to whom she is secretly married. The problem is that Blansac is in love with her, too, and, by the end of the opera, climbs up that same ladder for what he has been led to think is an assignation with Giulia.

Yup, we’re in the world of opera buffa, and there’s also a guardian around (like Doctor Bartolo in The Barber), named Dormont, and a male servant, Germano, who sticks his nose into other people’s business (but he’s less perceptive than Rossini’s Figaro, or Mozart’s). Plus there’s that other young lover, Blansac, as I said, and Giulia’s lovely cousin Lucilla, who ends up coupled happily with Blansac. This frees our main lovers to go off into a life of mutual affection that, to judge by the music written for them, they both richly deserve.

La scala di Seta (1812) is an early work by Rossini: opera no. 4 out of 39 or so (depending on how one counts), written when he was only 20. But, like some other opera composers (Handel, Mozart, Bellini, Bizet), Rossini developed early. String orchestras (and chamber ensembles) still perform his six “sonatas,” written when he was reportedly 12. His very first non-student opera, La cambiale di matrimonio, written when he was 18, is highly accomplished and witty; it gets performed rather often. As indeed does the opera heard here: there have been at least five previous audio or video recordings, featuring such notable singers as Graziella Sciutti, Olga Peretyatko, Cecilia Bartoli, Ernesto Palacio, Ramón Vargas, and Alessandro Corbelli. Plus dozens of recordings of its peppy overture.

This complete recording comes from the “Rossini in Wildbad” festival, located in Germany’s Black Forest region. Like other recordings that I’ve reviewed from Wildbad, this one features singers who are dramatically alert and possess firm, compact, flexible voices. I was particularly captivated by two singers new to me: Sardinian soprano Claudia Urru and Swiss tenor Remy Burnens.

Listening, I felt the thrill of a real performance, aided by the spiffy orchestral playing by the Polish orchestra under Spanish conductor Pérez-Sierra. There must have been applause galore, but it’s been edited out quite carefully, except at the very end.

I have praised Pérez-Sierra’s Wildbad recordings of two later Rossini operas: Aureliano in Palmira and Matilde di Shabran. Tenor Michele Angelini and baritone Emmanuel Franco did admirable work on the latter recording as well.

Blansac (Eugenio Di Lieto) and Giulia (Claudia Urru) in the production of La scala di Seta at Germany’s “Rossini in Wildbad” festival.

The work is generally described as a farsa comica, meaning a one-act comic opera. But it’s a very full act, and could exist happily by itself as an evening’s entertainment, though in Rossini’s day a farsa was usually paired with another one-acter, and a ballet was added between them to make up quite a full evening.

I noticed a number of distinctive and welcome features. The part for the servant Germano is quite extensive, more, indeed, than that for the guardian/tutor Dormont (which is written for a tenor). The “other” male suitor, Blansac, is not a rival tenor but a bass, making for some striking contrasts in conversational exchanges and especially in ensembles.

The recording uses a critical edition prepared by Anders Wiklung for the Fondazione Rossini. It therefore excludes an aria that has sometimes been added for Blansac (and that Rossini composed as a stand-alone concert item, not for an opera at all and that, worse, includes trombones, instruments not present in this opera).

The score is a smallish basket of delights, including a quartet for Giulia, Dorvil, Germano, and Blansac that suddenly, at a dramatic point in the action, shifts its harmony down a major third (much as Beethoven will do more than a decade later in the Ninth Symphony, at the words “vor Gott”). Lucilla gets a perky one-movement aria, with parts for piccolo and sewing-machine strings.

Germano (Emmanuel Franco), Blansac (Eugenio Di Lieto), Dorvil (Michele Angelini), and Giulia (Claudia Urru) in the production of La scala di Seta at Germany’s “Rossini in Wildbad” festival.

Even more colorful is Giulia’s “Il mio ben sospiro,” a seven-minute multimovement aria, complete with plangent “tempo di mezzo” before the cabaletta. Its orchestration includes prominent parts for a solo English horn, two flutes, and other winds. Particularly striking is the English horn’s opening melody, whose drooping two-note phrases seem to anticipate the recurring theme in Berlioz’s Harold in Italy. The parallel is even clearer if you know the latter’s “Rob Roy” Overture, in which the Harold tune (more or less) is played by the English horn! Berlioz wrote “Rob Roy” during his year in Italy (1831-32). Did he attend a performance of Rossini’s Silken Ladder and fall in love with that English-horn moment?

The Naxos release has nicely balanced sonics, and the two CDs are being sold at barely more than the price of one. The libretto is said to be available online at Naxos.com/libretti, but that’s just a short synopsis; instead it’s here, though only in Italian. An English translation would have been a great help!

Three other recordings are available on DVD, which I’m sure is a great way to get to know a work like this (especially if they are subtitled in English). But, of the previous audio recordings, only the one with Ramón Vargas seems to be commercially available right now.

However you get to know it, you’re sure to be entertained, and maybe also to wonder why Rossini, and comic opera generally (and one-acters, whether comic or serious), don’t get quite the respect that they deserve.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: José Miguel Pérez-Sierra, Kraków Philharmonic, La scala di Seta, Naxos, opera buffa, Ralph P. Locke