Opera Album Review: A Rossini “Semi-Serious” Opera That Works Like a Charm

This new recording would be a great, and inexpensive, way to enter the sound world of Rossini’s mature operas.

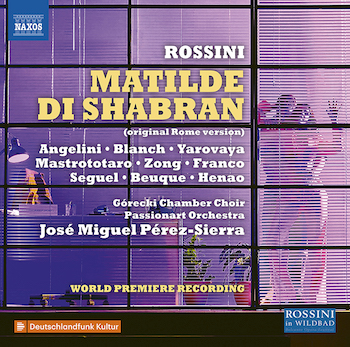

Gioachino Rossini: Matilde di Shabran (Rome version, 1821)

Sara Blanch (Matilde), Victoria Yarovaya (Edoardo), Michele Angelini (Corradino), Emmanuel Franco (Aliprando), Giulio Mastrototaro (Isidoro), Shi Zong (Raimondo).

Gorecki Chamber Choir, Passionart Orchestra, cond. José Miguel Pérez-Sierra.

Naxos 660492-94 [3 CDs] 197 minutes

Matilde di Shabran is one of Rossini’s most fascinating and accomplished works, the last of a series that he composed for Rome, where he had had major successes, including The Barber of Seville and La Cenerentola. Since 1815 he was primarily headquartered in Naples, where he primarily wrote, for two different theaters, serious works that would become the stylistic and structural basis upon which Donizetti, Bellini, and Verdi would build their own numerous serious operas.

Matilde di Shabran is one of Rossini’s most fascinating and accomplished works, the last of a series that he composed for Rome, where he had had major successes, including The Barber of Seville and La Cenerentola. Since 1815 he was primarily headquartered in Naples, where he primarily wrote, for two different theaters, serious works that would become the stylistic and structural basis upon which Donizetti, Bellini, and Verdi would build their own numerous serious operas.

Matilde, first performed in February 1821, was, by contrast, a work with a very mixed tone, blending serious threats and comically exaggerated characterizations. The technical term was “opera semiseria.” (Better-known instances include Rossini’s own La gazza ladra and Bellini’s La sonnambula.) The secondary role of Isidoro echoes that of Figaro in Barber, though he is an itinerant poet rather than, like Figaro, a man of multiple practical skills. Isidoro’s entrance-aria has passages that are strikingly similar to ones in Figaro’s own entrance-aria, the famous “Largo al factotum.”

The opera’s serious aspect is concentrated primarily in the tenor role: Corradino is a tyrant who claims to hate women, but ends up being tamed by the fearless Matilde, though not before Corradino tries to get her thrown off a cliff—a plot point that some characters on stage do not take very seriously. The general lightness of the music (and of the required singing style—this isn’t Wagner!) encourages the listener to accept Corradino’s viciousness as analogous to that of a fairy-tale tyrant who will eventually be brought to see the error of his ways. As a result, I am persuaded — in the course of this work more than any other — of the rich advantages of the semiseria genre.

Perhaps this blending of the serious and the ridiculous has caused the work not to fare well since Rossini’s day. Surely most opera fanatics, like myself, had little awareness of it until a 2004 recording. This used the version that Rossini prepared for Naples half a year after the Rome premiere, and it featured Juan Diego Flórez and Annick Massis (on Decca). Then came a DVD of a splendid 2012 production from the Rossini Festival in Pesaro, featuring Flórez again, plus Olga Peretyatko (Decca, again). The latter is one of the best DVDs of any Rossini opera, which is saying a lot because the competition is stiff, with fine video versions available of Barber, Cenerentola, and even the once-unknown La donna del lago.

Here we have a world-premiere recording of the original Rome version of Matilde. (There was an intermediate version for Vienna, available on Bongiovanni.) The recording blends three performances from a July 2019 staged production at a Rossini festival held every summer (well, not 2020) in the German town of Wildbad, which is located in the Black Forest region.

The work’s full title is Matilde di Shabran, or the Beauty and the Iron-Hearted One, a phrase that refers to Matilde’s attempts — eventually successful — at breaking down the resistance of her captor, the ferocious Corradino. The work third major part, Edoardo Lopez, is a pants role for mezzo or alto, and there are several appreciable passages involving several other characters as well.

A scene from the 2019 Rossini Festival production in Wildbad. Photo: Patrick Pfeiffer.

The cast is not as world-famous (yet) as on the Decca CD and the Decca DVD. But most of the singers hold their own quite admirably: I gather that the hall at Wildbad is not enormous, because nobody is forcing their voice to carry over a great distance. Even better, nobody is afflicted with an annoying wobble. To be accurate, Giulio Mastrototaro, as the aforementioned Isidoro, is often unsteady, but I was troubled even more by his tendency to hit a note a bit off-pitch and sometimes to half-speak it. Perhaps he was effective on-stage in this role of a pretentious bumbler, but all we have here is the portrayal’s sonic aspect.

Fortunately, the main roles are cast at full-strength: tenor Michele Angelini (as Corradino) is a real discovery, brilliant in coloratura (if a bit weak on his lowest notes), Sara Blanch is, by turns, fiery and touching as Matilde, and Victoria Yarovaya continues her triumphant series of Rossinian portrayals in the pants role of Edoardo Lopez. (See my reviews of Demetrio e Polibio and Bianca e Falliero, both in the March/April 2018 issue of American Record Guide, and Maometto II, reviewed at OperaToday.com. Yarovaya is apparently the same singer who, in earlier years, recorded under the name of Victoria Zaytseva.)

The most unexpected discovery for me here was the leading baritone, Emanuel Franco (Aliprando), who tosses off the coloratura as fluently as the soprano in their multi-sectional duet in Act 1.

Certain of the singers interpolate a loud high note near the end of a number, something that the audience clearly loves but that feels to me a bit crude compared to the work’s (and this performance’s) prevailing stylishness.

The orchestra and chorus (both from Poland) are conducted at brisk but flexible tempos — just right, in other words — by conductor Pérez-Sierra, whom I was first pleased to encounter in Rossini’s Aureliano in Palmira (see my review at OperaToday.com). The spiffy fortepianist Gianluca Ascheri adds little humorous bits — just enough, not too often. To get a sense of the riches on display, you can listen to any track in its entirety on YouTube.com, or hear the beginning of each track on such sites as www.naxos.com or hbdirect.

Applause has been edited to a bearable minimum. The booklet-essay is helpful, though in tiny type. The libretto is available online, which is helpful also for people who stream or download instead of purchasing CDs. But it is only in Italian. (Hiss, boo!) Music lovers outside of Italy would surely love to follow this recording with an English translation. After all, English is increasingly the international language understood in countries as different as, say, Brazil, Sweden, Hungary, and Japan.

A scene from the 2019 Rossini Festival production in Wildbad. Photo: Patrick Pfeiffer.

This new recording would be a great, and inexpensive, way to enter the sound world of Rossini’s mature operas. It fascinates as it goes along, thanks in part to its mingling of serious and comic elements. And it allows us to hear the composer’s first thoughts on some numbers, as well as a few (highly competent) numbers that Giuseppe Pacini composed for the Rome version and that Rossini later replaced.

Another difference: Isidoro sings in standard Italian here, whereas, for Naples, consistent with a long tradition in that city, the role was rewritten in local dialect. Alas, this, along with many other basic facts about the three versions, goes unmentioned in the otherwise helpful booklet-essay.

Committed Rossinians will want to have this well-performed world-premiere recording of the Rome version. For the mainstream (non-specialist) opera lover, and if price is right, either of the Flórez releases remains a more basic recommendation.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Gioachino Rossini, Gorecki Chamber Choir, Matilde di Shabran

[…] enjoyed Elena, which is an opera semiseria by Donizetti’s Bavarian-born teacher G. S. Mayr, and three Rossini releases: Matilde di Shabran (though the new recording is outshone by previous ones featuring Juan-Diego Flórez); Moïse [et […]