Jazz Album Review: Ornette Coleman — Very Much the “Genesis of Genius”

By Michael Ullman

Ornette Coleman turned to me and said, “You know, you can never really be out of tune. You are always in tune with something.”

Ornette Coleman, Genesis of Genius: The Contemporary Albums (Craft Recordings, CR00320)

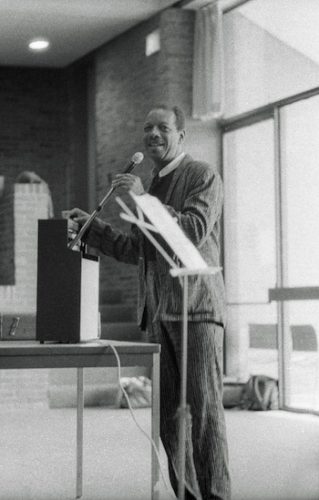

A smiling Ornette Coleman. Photo: Michael Ullman

Once, when I was walking with him to the student radio station at Tufts where I would interview him, Ornette Coleman turned to me and said, “You know, you can never really be out of tune. You are always in tune with something.” It’s a hopeful thought. On these early Contemporary recordings, Something Else! The Music of Ornette Coleman (1958) and Tomorrow Is the Question (1959), we hear Coleman finding what, and who, he is in tune with. These, his first two albums, were recorded by the intrepid owner of Contemporary Records, Les Koenig. Originally engineered by Roy duNann, the sessions have now been reproduced by Craft Records on two heavy, delightfully silent vinyl records and sit inside a blue box decorated only with the exclamation points that marked the original design of Something Else! The package contains a new essay by Ashley Kahn, but it is hard to beat the value of the long biographical essay Nat Hentoff wrote as the notes to Something Else!, which are also included. I compared the sound of these new discs with the copies of these sessions I bought in the ’60s. To my ears — and I must concede that my originals are worn — the new Craft LPs sound sharper, the stereo effect cleaner and more precise.

Coleman was, of course, controversial at the time of these recordings. He believed any note could be made sharper or flatter to fit his personal expression. His boppish lines struck some critics as irresponsibly irregular; others found his improvisations to be an uneasy sort of wandering. His tone could have a kind of bark in it. In other words, he took some getting used to. His rhythms are different, yet his songful compositions are memorable and, to my ear, lighthearted. In person, he seemed the least threatening man alive: even his titles, such as “Congeniality,” “The Blessing,” “Compassion,” “Peace,” and “Focus on Sanity,” are ingratiating. In an interview in 1984, Charlie Haden described to me his early times in Los Angeles with Ornette. I asked him, perhaps rudely, if he always knew what to do when playing with Ornette. He responded: “Not all the time. It was just so new. We were just beginning to formulate what we were hearing. Every time I play with Ornette Coleman, even now, this stuff happens that’s surprising, and you learn from it, because it’s still being formulated and I guess there’ll never be an end to it. It’s a way of improvising that has a desperate kind of urgency for spontaneity that you don’t have with regular, traditional jazz improvisation. Because you are actually creating a new chord structure on the original piece you are playing.”

Lester Koenig auditioned Coleman and trumpeter Don Cherry accompanied the saxophonist on piano. Koenig liked his tunes and took a chance, matching the horn players with pianist Walter Norris, bassist Don Payne, and drummer Billy Higgins. This was the album that would become Something Else! Only Higgins (and of course Cherry) would have a long musical relationship with Coleman. The other longtime drummer who became part of Ornette’s world was the New Orleans born Ed Blackwell. Haden explained to me the differences between them: “Blackwell will play hornlike behind Ornette. He’ll complete a phrase that Ornette started.… I always say that Billy’s like a waterfall. It’s just always flowing. He knows how to lift everything up. Blackwell does that too but he does it more with rhythmic phrases like a horn, and Billy’s concept is more kind of choral…. when he’s playing a solo, he’s playing a solo, he’s playing on a musical instrument.” One of the delights of the sometimes overlooked Something Else! is hearing Higgins and Coleman at the beginning of their time together. The percussive lift that Haden describes is omnipresent, even when, as in Coleman’s solo on the sweetly bouncy “Jayne,” the saxophone seems to be descending some scale that only he knows. With Coleman’s generally pianoless recordings to come, fans have often dismissed this first session. That would be a mistake. The playing is bright and vigorous, and pianist Walter Norris, who would go on to have a distinguished career of his own, is tactful: his harmonic suggestions are the product of his bebop training, of course, but they are unobtrusive. He’s more active behind Cherry than Coleman. Don Payne sounds fine. The compositions include the oft played “When Will the Blues Leave.” Like Lester Koenig, I find Coleman’s tunes extraordinary.

Recorded a year later, in January and February 1959, Tomorrow Is the Question! The New Music of Ornette Coleman eliminated the piano, thereby opening up the harmonic paths that each soloist could take: the quartet consisted of Coleman and Cherry, the Contemporary Records stalwart Shelly Manne on drums, and either Red Mitchell or Percy Heath on bass. The title cut is typical of a certain kind of Coleman composition: there will be a pleasingly bouncy melody followed by a passage that sounds like a scramble. “Tears Inside” sounds at first like swing: on this number, Cherry’s round-toned solo is particularly appealing. In “Compassion” Coleman makes way for the rhythm section: it begins with bassist Heath in duet with Manne. The composition comes in several parts, including what I hear as a hint of Tex-Mex. (Remember — Coleman recorded two versions of his “Latin Genetics.”) The soloist is able to improvise on any part of the melody that appeals at the moment. Coleman is at his wildest on “Rejoicing,” playing anxious flurries of notes, pausing, then offering a kind of upward scale passage, which he reworks before going on to something else.

There’s a musical logic to it all. In the case of “Rejoicing,” Heath and Manne play double time at Cherry’s entrance. One can hear Red Mitchell, another remarkable musician (listen to his duets with Jim Hall) on side two, which contains the longest and also most popular cut, the blues Turnaround. The tune has been recorded by persons as diverse musically as Pee Wee Russell and Pat Metheny. “Turnaround” allows Mitchell to take a lyrical blues solo. Its line is immediately memorable, as is the entire performance. “Turnaround” also finds Coleman playfully quoting “If I Loved You.” The second side opens, though, with the threatening sound of “Lorraine,” played in unison by the two horns, with long pauses between phrases. Then there’s a scrambling section, in humorous contrast. It’s a piece of two moods (a touch schizo), as if the composer didn’t want to restrict the polarized attitudes of the other players. The improvisation begins with the rhythm section walking in four, but they are asked almost immediately — by Coleman’s solo — to break up the rhythm. Manne’s solo is a delight. It’s interrupted by the horns playing their rapid-fire line.

Lionel Hampton once said about working with Benny Goodman: “When you became a part of Benny Goodman’s band, you became a part of Benny Goodman.” In the course of his career, Coleman would perform with surprisingly few musicians. Among the stalwarts: Cherry and Higgins, Blackwell, saxophonist Dewey Redman, and bassist Charlie Haden. Being in Coleman’s band meant, it would seem, after endless hours of rehearsal and many performances, becoming part of Ornette. And Ornette became part of them. These early recordings are something else: we hear Ornette, Cherry, and Higgins taking up the best in traditional jazz and finding a way to talk together about something new — in a deeply satisfying way.

Editor’s Note: Take a look at Arts Fuse critic Steve Provizer’s thoughts on Ornette Coleman — here and here

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: Craft Recordings, Genesis of Genius: The Contemporary Albums, Michael Ullman, Ornette Coleman