Jazz Commentary: Ornette Coleman — An Outsider Cracks the Egg

By Steve Provizer

The final, ineluctable quality that Ornette Coleman brought to the table was that he had an individual “voice,” which is the sine qua non and preeminent ethos in jazz.

There are two ways a musician can make a significant impact on jazz. One is to mobilize virtuosity and knowledge in ways that push the current boundaries of the music. Many fall into this category; the unassailable examples would be Louis Armstrong, Art Tatum, and Charlie Parker. The other way to make an impact is to bring an alternative approach powerful enough to challenge the preexisting musical paradigm. Ornette Coleman was the prime instigator of such a challenge in the late ’50s. Let’s look at how it happened.

Several branches had grown out of bebop in the ’50s: Cool, West Coast, Third Stream, Hard Bop, Latin and Brazilian-tinged jazz. But these were all closely related to the music created in the ’40s by Bird, Diz, Monk, and cohorts. For example, Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue and John Coltrane’s Giant Steps were recorded in 1959. Both of these represented a stretching — not a breaking — of the boundaries of jazz. For Miles, this meant asserting a simple alternative (modes) to chord changes; Coltrane pushed chord changes as far as they could go. After Coleman’s arrival, Coltrane would push even harder on those boundaries.

There had been a few previous attempts to free jazz from swing and bop constraints. In the late ’40s, Lennie Tristano began experimenting in free group improvisation; he recorded and multitracked free piano performances in the early ’50s. In the mid-’50s, Cecil Taylor and, to a lesser degree Sun Ra, made disruptive music. They received some critical attention and avid listeners, but their music had not yet reverberated beyond a fairly small group.

Jazz musicians had historically depended on a short list of criteria to evaluate whether a particular musician was worthy of attention. The most important: can the player “cut the changes” in tunes like “Cherokee” or Coltrane’s “Giant Steps”? Some value was also given to music writing and/or reading skills. One can characterize both of these skills as being more “professional” than aesthetic. On the other hand, a more ineffable quality was also indispensable — having an individual “sound” — a readily identified combination of tone and the notes that were identifiable as your own.

Ra had performed as pianist with Fletcher Henderson’s big band and Taylor was conservatory-trained. In other words, their musical explorations could not be dismissed on the basis of a lack of technical ability. This added gravity to a contentious re-evaluation of just what “genuine” jazz criteria should be. Because of Taylor, Ra, and those they influenced — and the period’s attack on accepted aesthetic standards going on in other art forms — the question was being asked whether judgments based so strongly on the integrity of technique provided an essential yardstick. Or whether they merely stifled innovation. Coleman’s arrival brought that debate to a head.

The record is pretty clear about Coleman’s technical strengths and limitations. He’d started R&B gigging when he was 16, moved around the sax with facility, and had a strong, personal sound. Harmonically, he was limited. As outlined by Maria Golia in her biography (Arts Fuse review) and from first-hand testimony told me by a friend who played with Coleman, he could not play mainstream chord-centric jazz. Throughout his life there are examples of Coleman being booted out of jam sessions by musicians who didn’t think he knew what he was doing. So, in the context of the verdict rendered by technical “chops,” it’s easy to understand why, in the wake of Coleman’s 1959 debut at the Five Spot Café, Miles Davis, Max Roach, Charles Mingus, and Roy Eldridge, among others, thought Coleman was jive.

At the same time, there were others who saw in him a unique and powerful voice. They weren’t concerned with what he couldn’t play — but with what he did. Such had been the case from Coleman’s teen years, when other musicians were eager to work with the saxophonist even when their own high level of skill could have gotten them other kinds of gigs. Ornette met many of these musicians early on and continued to work with them for the rest of his life.

At the same time, there were others who saw in him a unique and powerful voice. They weren’t concerned with what he couldn’t play — but with what he did. Such had been the case from Coleman’s teen years, when other musicians were eager to work with the saxophonist even when their own high level of skill could have gotten them other kinds of gigs. Ornette met many of these musicians early on and continued to work with them for the rest of his life.

Why did Coleman become the focus of so much attention, rather than Cecil Taylor? I think that one reason so much energy was generated around his appearance is that Taylor played piano and, at this point, wasn’t working with horns. Ornette played sax and had another horn in his quartet (pocket trumpet). Horns are, bluntly put, “in your face” — radical deviations from horn-playing norms tend to provoke visceral responses. Second, Ornette was all about the emotion and, at that point, Taylor’s playing was more about the head. The pianist had been influenced by modern classical music: his dense chromaticism and rhythmic displacements were challenging. The dissonance in Coleman’s music was less jarring: it wasn’t generated by the solos taken by the horns so much as a result of the subtle byplay between the rhythm section and the horns.

Although Coleman was smitten by bop as a young man, he never mastered it. One might say this left him free to develop a more emotional mode of expression of the sort that he’d witnessed in church and in the various dives he’d played. The music was direct — the blues was a vital part of his vocabulary. One might say that, rather than using chords to guide the process of tension and release, he created bands where the musicians looked to each other to do it. Finally, Coleman’s melodies were not hard to like — accessible, dance-like, logical, and sometimes, quite sad.

In a broad sense, one might say that although Coleman jettisoned some of jazz’s traditional underpinnings — primarily harmonic but to some degree also melodic and rhythmic — his music continued to operate in what I would call a “zone of emotion” that was familiar to jazz listeners. Those not put off by his rejection of those accepted trappings could hear and understand the “story” he was telling.

The final, ineluctable quality that Coleman brought to the table was that he had an individual “voice,” which is the sine qua non and preeminent ethos in jazz. The pleading, brash, sometimes squabbling, sometimes stentorian sound of his alto sax was immediately recognizable. Had he weakened his voice by straining to do something he could not, he would have kicked the pillars out from the edifice he had built.

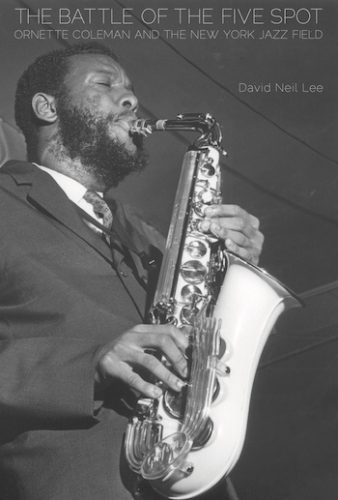

Ornette Coleman in action in 2005. Photo: Wiki Commons/Andy Newcombe.

I would not pass a litmus test as a true believer. I’m most enamored of his early acoustic quartets with the likes of Don Cherry, Charlie Haden, Billy Higgins, and Ed Blackwell and am only sporadically a fan of the electronic wash made by his band “Prime Time.” I can be frustrated by the limitations of Coleman’s harmonic understanding when I hear too many permutations of pentatonic scales. I also feel severely tested when listening to him play violin and trumpet. For me, this is a case of the uniqueness of a voice not being able to compensate for a lack of technique.

Ornette was the right man at the right time. His outlier status as a Texan was anything but a hindrance, while his idiosyncratic “look” seemed to strike a chord. In some ways, he was the beneficiary of the groundwork laid down by other boundary-breaking musicians and of the shift in American culture generated by Abstract Expressionism, nonnarrative filmmaking, Beat culture, and increasing interest in Eastern thought. The ground had been stirred up, but the vortex that was Ornette created a vacuum — and many walls collapsed.

His was more than just an innovation that roiled up the ’50s. Sixty or so years later, his music still has the power to shake, amuse, and move us. In many ways, Coleman was neither a sophisticated or educated man. But would any of us trade some of our refinement for a little bit of Ornette’s creativity and strength of purpose? I think so.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Thanks for this illuminating piece. Back in the mid seventies I spent time listening to Ornette Coleman, trying to balance out my burgeoning interest in jazz saxophone. Alas, however; I never quite “got” him and he went by the board for me in favor of Coltrane, Art Pepper, Stanley Turrentine, et al. Your review opened some new doors for me. Love when that happens, even late in life.

Great writing and historical take Steve, and I’m with you re Prime Time, trumpet , violin & even his drummer son – his legacy needs to be prime music, Jazz ciriculum…Yet while at least I enjoy hearing him on record or his music arranged live, he’s conservative (avant) compared to today’s Free Jazz which is one reason why I have my series, to hear the new influences which really honors Ornette as a father figure of the alternative, yet “ancient to the future” (AEC) which is an inspiring motto, the AEC having as much influence on me as I bet on creative musicians…Keep the torch lit Steve!

Thank you, Alex, for your complimentary response-and thanks for the work you do to keep new music in front of the public.

You need to rewrite the second to last sentence in your piece because it is utter bullshit “Coleman was neither a sophisticated or educated man .” What is your evidence for this ludicrous statement ? Did you meet or converse or engage with Ornette, ever see his book library or his art collection. Pure crap on your part to write this way. Also you mention your own refinement versus Coleman’s, your entire article has this kind of condescension running through it. Its typical of white assumptions about black artists.

No, I didn’t know Coleman, although I know people who did. So, my information is second hand-although you don’t say yours is first hand. There is a lot in the recent biography of him that I reviewed in Artsfuse that corroborates my perspective. The record says that he was not educated, although of course that doesn’t mean he was not intelligent. I’m sure he was. He was au courant with trends in art and “sophistication” is in the eye of the beholder, so perhaps that was too loose a description. Finally, until you read what I have written about many black artists, I won’t take your comment seriously that my writing is “…typical of white assumptions about black artists.”

I knew Ornette, the conversations we had and his perspective on life were second to none. He transcended his thoughts and ideas into musical sound.

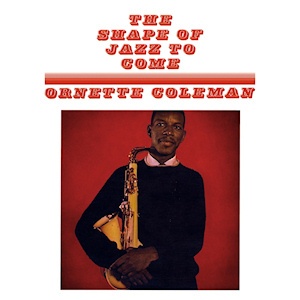

Quite serendipitously (and providentially), Ornette Coleman was my way into jazz from rock in 1970 when I picked up a mono copy of “The Shape of Jazz to Come” in a Woolworth’s bargain bin after having seen the name somewhere, maybe Rolling Stone). Not a bad place to start. I didn’t have to listen my way out of 1940s and 50s bop (Charlie Parker on first listen, for me, was more daunting that Ornette or Cecil Taylor), etc. His music communicated clearly and directly.

If you want to hear the sound of a pig having its toenails torn out with a pair of plyers, Ornette’s your man.

When I was a youngster, I was intimidated into listening to this junk, as well as Pharoah Sanders screeching with Trane. Now, I am not afraid to call it what it is.

Actually, Pharoah can play the saxophone properly. “Crescent With Love”, for example, is lovely. But that stuff with Trane was just a noise.

“Jazz Stunts Are Shattering Our American Nerves”:So Prof. Dykerna Declares as

He Deplores the Rhythmic Attack on Morals and Health, and Likens the Trap-Drummer to a Voodoo Worshipper

The Morning Tulsa Daily World (Tulsa, OK), December 3, 1922

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/data/batches/okhi_jackson_ver01/data/sn85042345/00237284380/1922120301/0346.pdf

Interesting article. The author only seems to be thinking of soloists: “ There are two ways a musician can make a significant impact on jazz. One is to mobilize virtuosity and knowledge in ways that push the current boundaries of the music. Many fall into this category; the unassailable examples would be Louis Armstrong, Art Tatum, and Charlie Parker. The other way to make an impact is to bring an alternative approach powerful enough to challenge the preexisting musical paradigm.” Duke Ellington does not fit in either of the “two ways.”

Thanks for your comment. Yes, I was referring only to soloists. Ellington’s influence is vast and while his comping and soloing are certainly individual and identifiable, that isn’t how he made his mark.

Your analysis of Ornette and his music is gratuitous to say the least. Only an unsophisticated person could define him so crudely. It is very unfortunate that you did not get to know him, his environment, his music, his philosophy of life and his teachings, any better then you did. Indeed you mention Maria Golia’s book, that alone speaks for itself. I’m sorry you did not get to meet him. You would be in awe. Serious criticisms starts with serious analysis and not opinions.