Album Review: “Mingus: The Lost Album from Ronnie Scott’s” — A Rich Centennial Treat

By Michael Ullman

The centenary of bassist/composer Charles Mingus’s birthday is days away and I am listening to the beautifully packaged and processed and richly annotated 3 LPs of Mingus’s Lost Album, recorded live at Ronnie Scott’s London club in 1972.

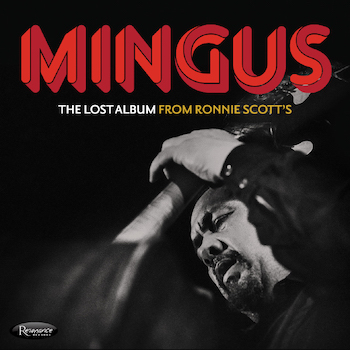

Mingus: The Lost Album from Ronnie Scott’s (Resonance Records)

As I write, the centenary of bassist/composer Charles Mingus’s birthday is days away (April 22), and I am listening to the beautifully packaged and processed and richly annotated 3 LPs of Mingus’s Lost Album, recorded live at Ronnie Scott’s London club in 1972. Mingus was what people like to call a force of nature, the greatest of bass players (in my estimation), an extraordinary composer (Let My Children Hear Music), and a fierce and enlightening bandleader. I always thought that going to hear Mingus was an adventure. He was as moody as can be. I first heard him on record when I bought the 1959 masterpiece Blues and Roots, with its shouting gospel numbers, wildly expressive blues, and a delightful tribute to Jelly Roll Morton, “My Jelly Roll Soul.” Powerful, gutsy, and impassioned, with solos by Booker Ervin, Jackie McLean, and others, it’s still my favorite Mingus record. Its soloists sound free and expressive and yet the music always sounds like Mingus. Then I heard the man live and he was shouting things like, “I know what I know,” rushing into double time during solos to challenge his musicians and playing acoustic bass with Boston’s Jazz Workshop, I believe), he was as quiet as a mouse. He had recovered by 1972, as we can hear in this band, which, except for Jon Faddis on trumpet, I also heard at the Jazz Workshop.

We all have favorite Mingus stories. Pianist Jaki Byard liked to tell of the time he got a wild ovation for a solo in Europe and Mingus yelled to him, “Don’t ever do that again!” He meant don’t try to reproduce that solo because it was a success. I heard Mingus at the Strata West Concert Gallery in Detroit on a night he was feisty. The trumpet player was blowing as hard as he could and Mingus kept yelling, “No, not like that.” Finally, he told the band to hush and he began a blues solo quietly as if to soothe himself. That solo seemed to grow in power until it felt like the walls might come tumbling down. I and other members of the audience ended up standing in a group around his bass. When he finished he looked over the audience, smiled sweetly, and went on with the show. It turns out he couldn’t stand bad music, even if it was his own. That was the one time I talked to Mingus, and I remember him looking warily over a very professional looking tape machine set up in an alcove. (Recently, Mingus: Jazz in Detroit/ Strata Concert Gallery (BBE Music) has been issued. He may have had a reason to look concerned.)

The Lost Album sextet includes trumpeter Jon Faddis, then generally seen as a worthy young Dizzy Gillespie disciple, the bebopping alto player Charles McPherson, and the Kentucky-born tenor saxophonist Bobby Jones, who made such albums as Hill Country Suite and introduced a country flavor into the band. Filling out the rhythm section are pianist John Foster and drummer Roy Brooks. In London, and elsewhere, the latter two are given opportunities to show off their sub-specialties. Foster does what is to me an embarrassing imitation of Louis Armstrong’s singing on “Pops.” (All vocal imitations of Armstrong are embarrassing.) Brooks takes a blues solo on the saw, which I saw him do in Detroit, bending the household item to produce standard blues pitches. As Samuel Johnson said of another kind of performance, it wasn’t that he did it well, it’s that he could do it at all that seemed remarkable.

The album was supposed to be issued, if I correctly understand the notes, by Columbia Records, but then its president Clive Davis dumped Mingus as well as Bill Evans, Keith Jarrett, and Ornette Coleman in one fell swoop. Each musician had just produced a masterpiece recording. (Ornette’s Science Fiction, Jarrett’s Expectations, and Mingus’s Let My Children Hear Music.) The Ronnie Scott set was therefore professionally recorded and sounds it. It consists of lengthy renditions of six Mingus pieces with Charlie Parker’s “Koko” and Benny Goodman’s “Air Mail Special” used as short themes.

The collection begins with a 30-minute version of the gorgeous Mingus ballad, “Orange Was the Color of Her Dress, Then Silk Blues.” The band plays an appropriately loose version of the melody, after which McPherson starts to solo. Like all the members in this band, one can almost feel him listening, pausing briefly as if awaiting one of Mingus’s rhythm changes, moves into double timing or other variations. Sometimes McPherson’s solo is a duet with his leader; at other times it is a rushed competition with the band. Faddis is next, and he is subjected to the same spontaneous changes in accompaniment. Mingus strolls at one point, then plays a bar of double time, and then issues a single anxiously repeated note. Faddis plays for a bit in the high note range for which he is famous and Mingus imitates him. At one point, everyone else is silent and Faddis introduces some Spanish-sounding phrases, and a little Charlie Parker. The performance stops and starts again. Eventually Mingus and Faddis are trading phrases, Mingus’s bass sounding every bit as robust as Faddis’s trumpet. These quicksilver shifts in tempo, rhythm, and texture, which continue with the other soloists, is unique with Mingus. Like Miles Davis, he had procedures which prevented his players from falling into improvisational ruts, even their own distinctive ruts. Mingus’s own solo starts the second side and is the final solo on “Orange….”

Charles Mingus at the Jazz Workshop in 1972. Photo: Michael Ullman

Mingus begins his “Noddin’ Your Head Blues” with one of his magnificent bass solos. John Foster then sings an Eddie Cleanhead Vinson blues tune so inoffensively that this listener wishes that Mingus were still playing solo. The solos that follow, including Foster’s, are fine. Mingus quotes the song “Blues in the Night” before Brooks takes a solo on saw. Of “Mind Reader’s Convention in Milano,” Mingus announces: “This composition is written to make things a little more difficult; in fact, it has made it so difficult we decided not to play it, but it’s written to feature our drummer Roy Brooks, and he said play it because it’s going to come out as magic.” It’s a bebop number with wide leaps in the jumpy melody. Its bridge sounds equally hard to play. In the group improvisation we hear hints of earlier Mingus tunes emerging. Eventually, the whole band seems to be improvising quietly over a repeated figure by Mingus, leading to another boppish written line.

Sides four and most of five are taken up with the now familiar Mingus anthem “Fables of Faubus” from Mingus Ah Um! and elsewhere. His tribute to Louis Armstrong, “Pops (aka) When the Saints Go Marching In” is a good-natured tune that reminds us that Mingus was once in Armstrong’s big band. “The Man Who Never Sleeps,” which Mingus introduces in his typical rapid mumble, turns out to be designed to show off Faddis. It’s another lazily beautiful Mingus ballad. The notes include, among other gems, an essay by biographer Brian Priestley, a long interview with Charles McPherson, and a tribute by bassist Christian McBride, whose favorite Mingus recording is also Blues and Roots. (Yeah!) Highly recommended, this music will soon also be on compact disc.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: Charles McPherson, Charles Mingus, Mingus: The Lost Album from Ronnie Scott’s, Resonance Records

I found Michael Ullman’s Review very helpful. I’d already purchased the triple lp set earlier on Record Store Day. In the mid sixties Mingus was playing at the Jazz Club [off Shudehill] in Manchester on a Saturday night.

With my teenage friends I’d travelled from Tottington through Bury. Despite attempts to be frugal with beer consumption, by the time we got got the Club for the second [all night] session at 11pm we had the [very modest] entrance price but nothing left for drinks! Reluctantly we went home on the late bus. I’ve always regretted that decision so getting this 1972 recording is a form of both tribute and compensation. I’ve a book re the history of Jazz in Manchester which refers to this gig. When Ronnie Scott died, there was a documentary [Ch4?] which revealed a cupboard at the Club that contained the recordings he’d had made. I’m assuming this is one of them! Ronnie played at The Bury Met on one occasion. The music was very good, of course but he had the audience in hysterics with his dry wit! Two great losses!