Jazz Album Review: Oscar Peterson Quartet — “A Time for Love”

By Michael Ullman

Oscar Peterson always seemed at his best live, which is how we find the pianist in this beautifully recorded, newly issued set.

A Time for Love: The Oscar Peterson Quartet Live in Helsinki, 1987 (three LPs, Mack Avenue)

Miles Davis criticized him for not leaving any space, and Herbie Hancock for his predictability. He’s also been praised extravagantly: virtuoso guitarist Joe Pass said that Oscar Peterson and Art Tatum were the only near perfect musicians he ever knew. Critic Leonard Feather said it was impossible to overpraise Peterson’s recordings. In his notes to If You Could See Me Now (Pablo), Benny Green called the session “not only daring but perfect,” and suggested that he was at a loss for words to describe it. (Nonetheless, he went on for four long paragraphs.)

Although I have reservations about some of Peterson’s playing, it’s hard not to be impressed by the pianist’s facility and, in his best years, his unfailing dynamism and fluid forcefulness. He had a remarkable range of techniques. He practiced!! Starting in the mid-’40s in his native Montreal, he recorded well over 400 sessions. He was discovered, one might say, for US citizens, by producer Norman Granz, who heard him on the radio in Canada. Once Peterson’s trio became a major draw, Granz found he could put the pianist almost anywhere in his Jazz at the Philharmonic concerts: behind Billie Holiday or Ella Fitzgerald, with a group of saxophonists like Johnny Hodges, Benny Carter, and Charlie Parker, with the fiery Roy Eldridge or the super cool Lester Young. In 1952 alone, Peterson recorded close to 30 sessions: among them dates with his drumless trio at Carnegie Hall, but also accompanying Benny Carter on Alone Together, and, in a less likely pairing, singer Fred Astaire in a mammoth session. He was one of Billie Holiday’s “lads of joy” band that year. He’s an excellent accompanist.

Peterson has always seemed at his best live, which is how we find him in this beautifully recorded, newly issued set, A Time for Love. It will be a pleasure for audiophiles as well as Peterson fans: he is in excellent shape here. (Six years later he would have a stroke that compromised his playing though it did not end his career.) A Time for Love has been released in three translucent blue recordings, which, when played, are silent as a tomb. When the music begins, the players are placed accurately and precisely — albeit a little distantly — and the balance is excellent. Peterson has rarely been recorded so well.

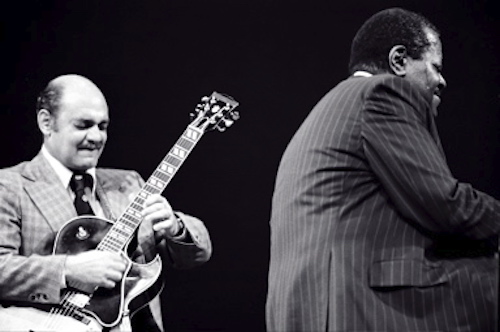

The first three sides (and one more number, “Blues Etude”) feature Peterson compositions. The opener, “Cool Walk,” is used to introduce the quartet one by one: first drummer Martin Drew, bassist Dave Young, and guitarist Joe Pass before Peterson himself. It’s a strolling blues that Peterson previously recorded on his album Time After Time. Peterson demonstrates here his characteristic gestures: downward scales (possibly cribbed from Art Tatum), huge tremolos, thumping locked-hands chords. He also shows how delicately and effectively he can state a pleasing melody. He continues with “Sushi,” a piece that seems to be based on “Sweet Georgia Brown.” Pass takes the first virtuosic solo: he’s stunning. Later, he’s given a solo feature with “When You Wish Upon a Star” and it is the highlight of the record. The performance would be a highlight on almost any album. The sidemen here are Peterson’s equals, and Pass is remarkable, as always. The pianist has arranged “Soft Winds” so that he has a conversation with bassist Young. Young solos on Peterson’s gentle “Love Ballade.” The sweetly unpretentious piano playing we find on this and the other ballads here is what primarily draws me to Peterson’s playing.

Guitarist Joe Pass and pianist Oscar Peterson. Photo: Wiki Common

An entire side is dedicated to Peterson’s “Salute to Bach,” a suite commissioned by the Bach Festival in Montreal to commemorate Bach’s 300th birthday. Peterson previously recorded it in 1986 on Oscar Peterson Live! (Fantasy). It begins in un-Bachlike manner with a pretty melody played solo by Peterson over his own restless left hand. This section comes to a halt and the rhythm section joins in with Peterson’s now more emphatic playing, drummer Drew reinforcing his accents. That melody is used as an introduction. When it ends, Peterson introduces a fugue in a staccato manner: he sounds like a man throwing darts. The band plays a driving, even frenetic sounding beat underneath a solo by Pass. It sounds more like mayhem than Bach. The air clears once Peterson takes over. Here opinions will differ. The more excited Peterson becomes the more he returns to his (well) practiced techniques. This listener was not caught up in the pianist’s exuberance. This section is followed by a slow movement played solo by Peterson, and the suite ends with a thumping blues.

Every time I saw him live, Peterson played some Ellington. Here he offers a 19-minute Ellington-Strayhorn medley. He starts with “A Train,” which he inevitably takes at a faster tempo than Duke ever did. He moves on to “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore,” throwing in some boogie-woogie along the way. Then comes a short version of “Duke’s Place (C Jam Blues).” After that Peterson supplies a busy solo version of Strayhorn’s “Lush Life.” He sounds impatient with the patiently languorous way that Strayhorn builds his ballad. This touches on the major problem I have with Peterson. Keats advised poets to “Load Every Rift With Ore,” and Peterson feels duty bound to fill every space with notes. He plays “Caravan” at a devastatingly fast tempo. His frenzied statement of the theme draws a round of applause — it sounds a little crazed to me. Eventually the quartet is left (temporarily) by the side of road as Peterson takes a remarkably technical solo. There are gentler tracks here, including Bill Evans’s “Waltz for Debby. The title tune, “A Time For Love,” was written by Johnny Mandel for the movie An American Dream. (One reviewer called the film, based on a 1965 novel by Norman Mailer, “tediously violent.”) The LPs finish with another up-tempo blues, accurately named “Blues Etude,” which is begun by the trio, without Peterson. I imagine the leader, always dramatic, was using the intro to prepare his entrance.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: A Time for Love: The Oscar Peterson Quartet Live in Helsinki, Joe Pass, Mack Avenue, Michael Ullman