Book Review: “Crown & Sceptre” — A Quick Walk Through the British Monarchy

By Thomas Filbin

Crown & Sceptre is generally amusing and it has the instructional benefit of helping readers keep the Williams, Henrys, Edwards, and Georges who have occupied the ancient throne straight.

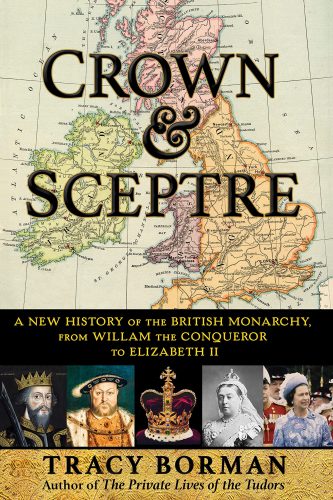

Crown & Sceptre: A New History of the British Monarchy, from William the Conqueror to Elizabeth II by Tracy Borman. Grove/Atlantic, 555 pages, $32.

Judging by the enormous popularity of The Crown, Downton Abbey, The Queen, and Helen Mirren, we Americans are not stalwart republicans (small r), but raving monarchists and wannabe aristocrats. What else explains the worship of mystique, this love of robes and coronets? Complex psychological theories can (and will) be called in, but the simplest explanation is that an unreasonable love of fantasy, power, and pageants eases the banality of everyday life.

Tracy Borman, a joint curator of Historic Royal Palaces and the author of numerous works on historical subjects, has written an entertaining one-volume compendium of the conquests (political and amorous), successes, failures, triumphs, skullduggeries, and follies of 41 monarchs dating from 1066 to the present. One of the curious similarities among the various houses — Normans, Plantagenets, Lancaster and York, Tudors, Stuarts, Hanoverians, and Windsors — is that very few could be considered strictly “English.” More French, Scottish, and German blood has flowed through the veins of British monarchs than any of them would ever care to admit. Perhaps, for American devotees of Masterpiece Theater and British sovereigns, that is part of the dream: you can become “English” if you want it badly enough.

It would be a marathon of a review to evaluate Borman’s take on all the royals. So here is a fair sampling of her selections, her method, and her judgments. She begins her story with the ascension to the throne in 1066 of William of Normandy, a bastard son who argued for the right of descent but actually employed the right of conquest. International law has always recognized some validity to the winner when he declares he has won. The Normans were a fighting lot and were finally able to suppress Saxon resistance after numerous rebellions. A new England was created, one where the kings spoke French for the first few hundred years. One of the Norman problems was that they now laid claim to ruling two geographies: England plus Normandy and all the related French fiefs. Constant forays to do battle with the King of France eventually led to the Hundred Years War (1337-1453). Feudalism, Borman notes, was the basis of European social structure and “William reinforced it with greater vigour than before…” with the king at the top of a social pyramid. In theory, he was the only landowner — all others were owners only at his discretion. The Domesday Book, a property listing for the time, remains a revelatory artifact. William’s choice to allow some English governmental practices to stand — they were more efficient than his Norman ones — led to a blending of cultures, not an eradication of the English processes.

Richard the Lionhearted (1189-99) was the stuff of legend, although Borman points out much of what we know of Richard, his brother King John, and pop culture figures such as Robin Hood and the Sheriff of Nottingham are more fiction than fact, true in some particulars but not all that accurate. Richard’s penchant for crusading, a habit of all medieval Christian monarchs, nearly brought England to ruin. He took long absences from the country to fight Saladin, with wicked John ruling in his stead, and endured being taken captive by Leopold of Austria (with friends like this…). He was not released until a ruinous ransom had been paid involving the intercession of his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, the pope, and the emperor. Richard was shot by an arrow while suppressing a revolt in France; his wound was mistreated by a surgeon so he died of gangrene at age 41. Sic transit gloria mundi.

Henry VIII is one of the most interesting figures Borman treats. She usefully cuts to the chase at the outset, noting how much Henry sought from the beginning of his rule to differentiate himself from his father, Henry VII. Possessed of a large, hulking frame (6 foot 2 and athletically built), capable at weapons of war, horsemanship, music, and dancing, Borman calls him an “extrovert, affable, and open handed, and could dominate as well as charm any gathering.” On the negative side, he had inherited his grandfather’s vanity, gluttony, and licentiousness. Initially, the Tudor age promised greatness, but the scandal of Henry’s affair with Anne Boleyn and the battle to secure a divorce from Queen Catherine threw the country into civil strife. The executioner’s axe was kept whacking. Woe to those who stand between a king and his will to power.

Historian Tracy Borman. Photo: Grove Press

Elizabeth I earns Borman’s admiration: “More than any other monarch, Elizabeth had learned from the mistakes of her predecessors.” Adept at propaganda and self-promotion, she surrounded herself with poets and playwrights who “conjured up potent imagery to reinforce both the legitimacy and strengths of her rule.” Because she never married to produce an heir, it would fall to her relatives, the Scottish Stuarts to provide the next four monarchs. Borman argues that Elizabeth’s reluctance to commit to any marriage prospect was a successful ploy. She wanted her courtiers to imagine her to be an indecisive woman who needed managing. She could use the element of surprise to turn the tables on them, demanding action when it was required.

Charles I, in Borman’s opinion, would have been a better king had he not been addicted to women. If you gathered together all of his mistresses and illegitimate children they would fill the throne room. That said, he did restore the “merry” to England by reopening the theaters after the grim interregnum of Cromwellian Puritanism. His brother, James II, lost the throne because of his crypto-Catholicism: he remarried an Italian princess who gave him a son long after it was assumed his daughter Mary would inherit and continue Protestant rule.

Borman quickly dispenses with the Hanoverians: George I was “an honest, dull German gentleman,” George II a dunce, George III quite mad at times, and George IV a playboy given to gluttony, drunkenness, and gambling, while William IV, a younger son, was amiable and informal and fathered Queen Victoria. Victoria gave her name to the age, her rule emblematic of a period dedicated to staid, formal, and ironclad probity. What the Hanoverians left in their wake was stability and illegitimate offspring, including the descendant of one of them becoming a Prime Minister: David Cameron.

Of the Windsors, Borman has little new to say, and perhaps this is a good thing. Historical judgments often need at least a century to ferment. Honesty is cultivated over time. Will there be a monarchy in a hundred years? It’s anyone’s guess. Perhaps it will morph into a more modest, more buttoned-down institution, like those in the Scandinavian and Low Countries. The kings there don suit and tie more often that crown and sceptre. The only hope that monarchs won’t be canceled is to make them less elevated, to become level with the people they rule.

Crown & Sceptre is not a deep dive; it is an effective, quick walk through the players and their times. The narrative is generally amusing and it has the instructional benefit of helping readers keep the Williams, Henrys, Edwards, and Georges who have occupied the ancient throne straight. Perhaps, when taken collectively, these royals are neither better nor worse than the cast of elected presidents we have endured.

I once saw the back of Queen Elizabeth’s head as she entered her car as it pulled away from one of the Oxford Colleges where she had come to make a dedication. To me, a life where every day is prearranged, filled with stilted visits, presentations, handshakes, and curtsies would be a bore. Aren’t we talking about life in an ermine-lined prison, the freedom to be one’s spontaneous self banished? Perhaps one day a savvy sovereign will just toss it all away, hand in the keys to the joint, and admit that, at this point, the game isn’t worth the candle: “Would rather ‘ave a life o’ me own, thanks.”

Thomas Filbin is a freelance book critic whose work has appeared in the New York Times Book Review, Boston Sunday Globe, and Hudson Review.

Tagged: Crown & Sceptre, English kings and queens, Queen Elizabeth, Thomas Filbin