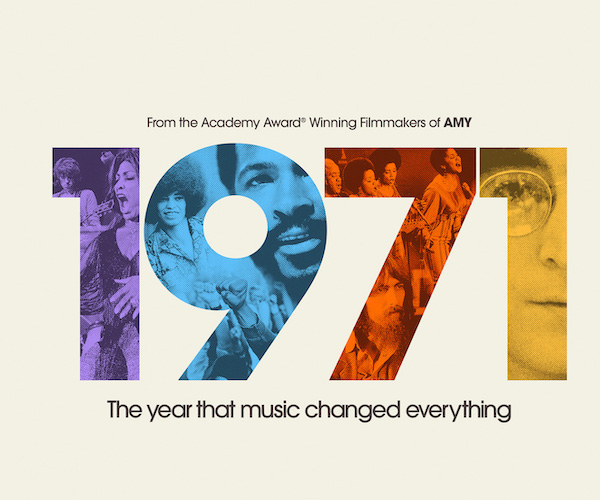

Television Review: “1971: The Year That Music Changed Everything” — Episodes 1-4

By Allen Michie

There are three key words in the title: “music,” “change,” and “everything.” At its best, the series convincingly shows how they are linked. Other times, it embraces too much of one at the expense of the other two.

1971: The Year That Music Changed Everything: Episodes 1-4. Apple TV.

Throughout 2021, “The 1971 Project” at the Arts Fuse has been celebrating the extraordinary music of 50 years ago. We are not the only media to recognize that, perhaps never before and never since, has one year proffered such a diverse range of quality popular music and such an ensemble of creative (often visionary) young artists finding their path. Since May, Apple TV has made available an eight-part documentary series, 1971: The Year That Music Changed Everything. It’s an exhilarating and exhausting cross section of a year that — for better or for worse, culturally and politically — set the trajectory for the future we’re still living in.

“The 1971 Project” on the Arts Fuse has taken both popular and overlooked albums and given stand-alone overviews and appreciations. Our artistic scope has been wide but our historical perspective has been limited: you’ll find not only some of the heavy-hitters like Carole King’s Tapestry and Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, but also revolutionary folk music from Chile, multimedia propagandistic Chinese opera, and Afro-Futurist avant-garde jazz. 1971: The Year That Music Changed Everything confines itself to the narrower artistic scope of rock, R&B, and pop music (with one notable digression into reggae). How the series probes the depth of US and UK history, however, is its main strength. There are three key words in the title: “music,” “change,” and “everything.” At its best, the series convincingly shows how they are linked. Other times, it embraces too much of one at the expense of the other two.

This review covers the first four one-hour episodes.

Episode 1, “What’s Happening,” establishes a pattern followed by the other episodes. An artist or group is singled out as a touchstone, and then the narrative branches out into current events and cultural movements, with other artists brought in as supporting evidence. Here the spotlight is on John Lennon, a fitting choice since the breakup of the Beatles marked both the literal and figurative end of the ’60s. The episode demonstrates that the music of 1971 established itself as much more than just a coda to the late ’60s. As an unidentified record store clerk puts it, “Vietnam was in your neighborhood. And to me, the music was not a soundtrack. It was much more than that. Because it infiltrated.”

Marvin Gaye — “What’s Going On,” described aptly by a listener as a Trojan horse. Photo: Apple TV

Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On is introduced in the context of Gaye being upset about his brother being sent to Vietnam and not understanding why America was there in the first place. There’s an extended and rapturous live version of “What’s Going On,” described aptly by a listener as a Trojan horse — it’s a stinging political commentary, but the adults were singing along with the kids because it was beautiful music. Gaye calls it a “divine project,” which it surely is.

There are scenes of the actual rehearsals and recording sessions for John Lennon’s Imagine. Lennon says he wanted songs of peace to be like Coca-Cola signs: the world so promotes war and violence that he wants to provide some balance. Rock music, he explains, can help “get people hooked on peace.” There’s a striking scene of John and Yoko on a riverboat, watching the Twin Towers get constructed. They were there to be international citizens of peace, and so much violence was ahead. “I don’t know how much effect we have. But what’s the alternative? To be apathetic and not bothered about anything? Then what would I do then? I just want to live.” He writes “Imagine by John & Yoko 1971” in the sand, and it is almost immediately washed away.

One of my favorite bits in the series is a jarring scene in the White House, where Richard Nixon introduces the easy listening Ray Conniff singers to the applause and beaming smiles of his all-white, all middle-aged audience. No comedy show could have come up with a skit that proved how sublimely out of touch the US president was with the cultural zeitgeist. Then one of the polyester-clad singers holds up a protest sign and politely gives a speech telling Nixon to stop the killing. If Jesus Christ were here, Nixon wouldn’t drop another bomb! Nixon smiles, seething inside. It’s amazing and completely unexpected footage. I would love to hear more about this astonishingly brave young lady and what became of her.

Episode 2 is “End of the Acid Dream.” It’s a portrait of 1971 as the hangover to the ’60s, the year when getting high stopped being fun and the realities of serious drug addiction cast a pall over the entire decade. As Robert Greenfield of Rolling Stone says, “Once you dissociated yourself from Main Street culture, you stopped reading those newspapers, you stop watching television shows, your entire imaginative life came from the music you were listening to…. And the people who are making that music were talking about things that you cared about. And you were high and they were high. Everybody felt like they were going in a certain direction together. But in 1971 it all started going in a different direction. We learned that the last people you wanna follow anywhere are musicians.” Many of these young listeners, no doubt, followed Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, and Jim Morrison to the end of the line.

It starts with one of the most disillusioning rock events of a disillusioning year: the Rolling Stones concert at the Altamont Raceway in San Francisco that went horribly wrong, with everyone apparently trying to get as high as possible as fast as possible, ending in four deaths. A Hells Angel stabbed someone near the front row. “Altamont was the Pearl Harbor of rock,” Greenfield says. “It was the death knell for the beautiful people, and the end of the ’60s. One world was ending, and another one was beginning. The peace, flowers, and love thing was over.”

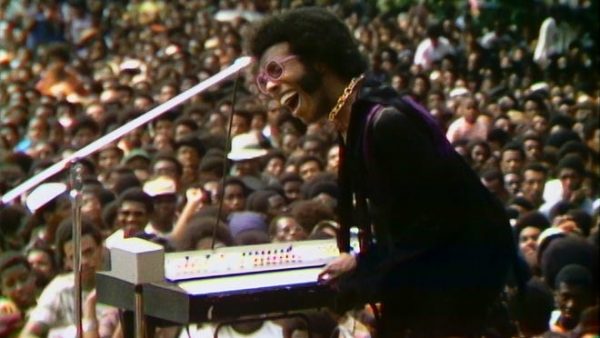

Sly Stone — emblematic of some of the ’60s stars who opted to disappear in 1971.

Then it’s Sly Stone, emblematic of some of the ’60s stars who opted to disappear in 1971, marking the disintegration of the optimistic counterculture into a haze of cocaine, which was replacing pot as the drug of choice. Stone is seen alone in his huge Bel Air house, recording fragments of what would become There’s a Riot Goin’ On, overdubbing and recording over his good material. Later, in episode 6, there’s a funny clip of a wasted Stone being interviewed on the Dick Cavett show, until you realize it isn’t funny at all. So many people took their own and other’s artistry for granted, like there could be an unlimited supply no matter the circumstances. Looking back on it 50 years later we sadly know better.

Then it’s on to Hunter S. Thompson, an honorary rock star, so it’s fitting that there’s an account of 1971’s jaded and cynical Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. “Hunter Thompson was a real piece of work,” Greenfield says. “Unlike most journalists back then, he always wanted to be the story. He called it Gonzo journalism, but it was just Hunter drunk, stoned, tripping, creating chaos wherever he went to get the kind of story he wanted.”

It’s all deeply depressing, but the episode ends on an odd and fascinating note that’s both uplifting and disturbingly prescient. This was also the year when Jesus Christ Superstar became an instant hit album. Parallel (but not exactly in opposition) to the trend toward hard drugs was a yearning toward spiritual extremes. The hippie movement was branching off in different directions. There were the Jesus Freaks and the Hari Krishnas. George Harrison staged his Concert for Bangladesh. “My Sweet Lord” was the #1 single of the year in the UK. There are creepy scenes of some blissed-out, cultish evangelicals preaching to young people; it’s difficult not to think of the Charles Manson cult (taken up in depth in episode 6). For a while it all looked sweetly harmless. Hunter S. Thompson always knew better: “We were riding the crest of a wide and beautiful wave. But that was some other era. Burned out and long gone from the brutish realities of this foul year of our lord 1971.”

Episode 3, “Changes,” is loosely about the origins of glam rock. Surprisingly, it’s traced back to the breakup of the scruffy and audience-adverse Beatles. Their separation sent fissures deep into the bedrock of popular culture. “The whole youth culture could not have happened without them,” says Annie Nightingale, a DJ for the BBC. “What I feared was that the establishment was going to claw back pop music to where it had been pre-Beatles. Awful, awful light entertainment. It was them or us.” We see David Bowie in the act of creating a new vocabulary for what rock music could be. “We were fed up with the hippies,” Bowie said. “We wanted to go somewhere else.” The American pop charts were “generally intolerant of weirdos,” as Bowie says, so he put on a dress. Later in the year, Bowie became Ziggy Stardust. Reg Dwight became Elton John. Vincent Furnier became Alice Cooper. Rock conscientiously merges with musical theater.

The episode zooms in for an extended look at an artist who made a limited impact in the US but who was huge in the UK: Marc Bolan, lead singer for T-Rex. He’s credited with advancing the theory of the pop single as well as following through with post-Beatles innovation. He also added a touch of progressive glam that helped draw crowds of screaming teenage girls. (Today, he’d pass for emo.) Meanwhile, in London, the underground press was thriving, especially the deliberately provocative magazine Oz, which eventually alienated the British evangelicals once its writers began promoting sex for teenagers. The editors were put on trial and the proceedings sparked a major youth protest movement in England, which is covered in much more detail in episode 8.

The Charles Manson verdicts in January gave conservatives the excuse they needed to see all people with long hair as Satanic deviants. One band in particular saw this as their perfect opportunity to launch, but in the diametrically opposite direction — Alice Cooper. It all seems quite tame now, but there’s hilarious footage of Cooper’s theatrical stage show, including Cooper swinging a watch on stage, literally hypnotizing his fans, delighted to give his vocal opponents (usually their parents) the nightmare that they feared.

The episode ends with the chaotic, muddy mess of the huge Glastonbury Festival, where Bowie premiered “Changes” while the sun was coming up at around 5 a.m. A few people clapped. His time had not fully arrived (stay tuned for episode 8).

There are some mixed messages here. On the one hand, we’re told that the hippie movement was conclusively over, killed by cultural cynicism, drugs, unending war, and artistic exhaustion. But what we see on screen suggests that the hippies had some life in them yet. In Episode 1, John and Yoko embody the hippie look and philosophy, and the crowd at Glastonbury looks to me like it’s chockablock with hippies. Clean before-and-after distinctions make for effective storytelling on TV, but the series could have done more to embrace the simultaneous and overlapping trends. It should have been talking more about a culture in transition than opposition.

Andy Warhol — we see his crowd doing its outrageous thing to the sounds of Lou Reed’s “Take a Walk on the Wild Side.” Photo: Apple TV

Episode 4 is “Our Time Is Now.” If Bowie thought that pop music was intolerant of weirdos, then this episode shows how non-weirdos could produce timeless music. You can go acoustic and still be a revolutionary. The heroines (free of heroin) here are Carole King and Joni Mitchell, with attention along the way to Elton John, Cat Stevens, James Taylor, and others at the start of the singer/songwriter movement. It’s hard to argue with Elton: “I don’t think you’ll see a creative outburst like that musically ever again. You could probably buy 10 albums a week that became pretty classic albums. I mean that’s astonishing.”

The music industry was shifting from New York to California, and along with it came a sunnier and freer aesthetic. The more important shift, however, was that in contrast to all the traditional love songs and their reinforcement of traditional gender roles, popular music was starting to question the role of the domestic suburban housewife. There was an honesty of desire, a call for respect, and an exploration of independence in the music of King, Mitchell, and Aretha Franklin. The episode has several powerful scenes of women recounting what King’s Tapestry meant to them.

The gay liberation movement was only in its most formative years. There’s footage of Andy Warhol’s crowd doing its outrageous thing to the sounds of Lou Reed’s “Take a Walk on the Wild Side.” It’s a stretch at this point to link this to Elton John, who didn’t come out as bisexual until 1976. Still, Elton’s theatrical expressiveness and individuality was an inspiration to many, then and now, and he expanded the opportunities for singer/songwriters into new dimensions of performance.

There’s a long interwoven look at a strange reality TV show, An American Family, that was enormously popular in 1971 but is largely forgotten today. It’s the story of a once-happy marriage falling apart, ending in divorce, with the former housewife strutting her way to independence to the soundtrack of “It’s Too Late,” “Natural Woman,” and “I Feel the Earth Move.” This part of the documentary went on a bit too long after it made its point, but it’s a strong example of the changed everything part of the series’ title.

Episodes 5-8 will be covered in an upcoming review. Watch this space, and if you’ve read this far, you’ll enjoy looking back over the Arts Fuse’s “1971 Project” entries for February, March, April, May, June, July, August, September, October, and November.

Allen Michie works in higher education administration in Austin, TX.

Tagged: 1971: The Year That Music Changed Everything:, Allen Michie

Another counter-hard drug, spiritual artifact was Bernstein’s Mass, also 1971.

True–it would have been nice to see that included, but the series doesn’t give one single minute to classical music.