Arts Reconsideration: The 1971 Project – Celebrating a Great Year in Music (November Entry)

Arts Fuse writers continue their countdown of great music celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. This month’s diverse list includes John Lee Hooker, Víctor Jara, the Grateful Dead, Grand Funk Railroad, and Yes.

Miles Davis once said, “Man, sometimes it takes you a long time to sound like yourself.” This month’s entry in the 1971 Project, appreciations of the powerful music that’s celebrating its 50th anniversary this year, spotlights artists who were at the start of finding their own authentic and unique musical voices. The young band members of Canned Heat had the good judgment to apprentice themselves to an established blues master, John Lee Hooker, who himself was still searching for new heights. Víctor Jara was rapidly becoming the musical expression of his country’s political resistance, the source of both his early demise and lasting fame. The Grateful Dead established their genre-crossing musical sound as well as their legacy of extraordinary live concerts. Grand Funk Railroad worked on their grand ambitions for what rock ‘n’ roll could be and what it could mean to people, and Yes aimed for nothing short of studio perfection as progressive-rock pioneers.

For those who missed them, here are the 1971 music entries for February, March, April, May, June, July, August, September, and October.

Let us know your reactions in the comments and tell us about your own favorites from 1971.

– Allen Michie

Hooker ’n Heat – John Lee Hooker and Canned Heat (Liberty)

An upshot of the ’60s blues revival was this kind of matchup between young white blues-rockers and their bluesmen heroes. (See Muddy Waters’s Fathers and Sons with Mike Bloomfield and Paul Butterfield; London Sessions recordings by Muddy and Howlin’ Wolf; and many others.)

An upshot of the ’60s blues revival was this kind of matchup between young white blues-rockers and their bluesmen heroes. (See Muddy Waters’s Fathers and Sons with Mike Bloomfield and Paul Butterfield; London Sessions recordings by Muddy and Howlin’ Wolf; and many others.)

So here was John Lee Hooker, then in his mid-50s (his date of birth is disputed), widely recorded and widely traveled, a “star” of the ’60s blues revival, but hardly a household name. The members of Canned Heat were all in their 20s and had had big pop radio hits in 1968 with “On the Road Again” and “Going Up the Country,” plus turns at Monterey Pop and Woodstock.

The grainy sepia-toned cover photo of Hooker ’n Heat plays on the era’s original-bluesman mystique: band members gathered in what looks like a corner hotel room worshipfully regarding Hooker as he looks at the yellow neon album title.

But mystique doesn’t necessarily mean not real. Canned Heat were serious about this stuff. A search was made for a guitar amp that would deliver “that real ‘Hooker’ sound” of his Epiphone guitar, and a plywood platform was built that would resonate with his ceaseless foot-stomping. Studio control-booth dialogue between tracks contributed to an atmosphere of good-humored vérité intimacy.

The album is divided evenly between one disc of solo Hooker and another of him with the band (plus a couple of duets with the band’s Alan “Blind Owl” Wilson on harmonica or piano). The band tracks are engaging, energetic jams, but it’s the first disc that makes this album a keeper. The raw, unadorned sound of voice and guitar establishes a deathless groove from the opening “Messin’ with the Hook,” sustaining aggressive bass lines with simultaneous trebly filigree, the riffing between the two instruments (the third being the elemental percussion instrument: foot) extending into solo-guitar outbursts. The tracks are laced with such spontaneous, improvised moments — Hooker trying to get at something. And having fun. On the boogie “Send Me Your Pillow,” the groove releases into an atonal-guitar percussion break (slapping tamped-down strings?), then a bass-string solo with a rhythmic vocal accompaniment: “ah-nittin-grittin-unh-unh-umm-umm.” The slow blues all have a searching quality, and when Hooker worries a lyric (“I should have been gone from you baby a long, long time ago”), the jagged guitar riff becomes an answering chorus to his imprecations. The guitar consoles the singer but is also an extension of his voice, of his need — the stuff you can’t put into words.

Hooker ’n Heat was the first John Lee Hooker album to make the charts. Wilson died before it was released. Canned Heat went through various lineups and dissolved after the death of cofounder Bob “The Bear” Hite, in 1981. Hooker had a late-career resurgence that continued from the late ’80s through his death in 2001, a period when, as the Penguin Encyclopedia of Popular Music has it, he was “one of the best-loved bluesmen of all time” and “the good and the great gathered around his feet.” Much as Canned Heat had all those years before.

– Jon Garelick

El derecho de vivir en paz – Víctor Jara (Dicap)

El derecho de vivir en paz – Víctor Jara (Dicap)

On September 11, 1973, a CIA-sponsored fascist coup would bomb the presidential residence of Chile in order to oust the democratically elected socialist Salvador Allende. Horrific repression followed, with many people being thrown out of helicopters to their deaths or simply disappearing. One of the most tragic losses to come from that event was the torture and death of Chilean artist Víctor Jara. The son of peasants, the guitarist and singer had become a shining light in the nueva canción (New Song) movement in Chile. A devout socialist, he would earn the respect of Bob Dylan and Joan Baez, befriend Pablo Neruda and Violeta Parra, and work beside Quilapayún.

Jara was imprisoned just days after the coup, along with thousands of others in Santiago’s Estadio Chile stadium; he was tortured for four days before being killed. A soldier in the stadium identified him, saying, “You are that Víctor Jara asshole, the Marxist singer, that shitty singer! … I’ll teach you to sing Chilean songs, you son of a bitch — and not communist ones!” In prison his fingers were broken and his tongue was cut out of his mouth. Throughout his ordeal, laughing soldiers commanded him to play guitar and sing.

So what made Jara such an inspiration and a threat? His sixth album, 1971’s El derecho de vivir en paz (The Right to Live in Peace) supplies some of the explanation. The words to the title song say, “The right to live, the poet Ho Chi Minh, which strikes from Vietnam to all mankind, no cannon will erase the furrow of your rice field, the right to live in peace.” Clearly not on the Kissinger top 40 playlist that year. Yet the song lives on in Chile and elsewhere as a protest against violent repression.

The album also features an ode to the Chilean communist Ramona Parra, killed during a protest in 1946. There is a collaboration with Peruvian composer Celso Garrido Lecca and an adaptation of a poem by Spanish Republican Miguel Hernández lamenting the life of a peasant worker. There is also an adaptation of Malvina Reynolds’s “Little Boxes” called “Las casitas del barrio alto,” although what’s being satirized isn’t the mundane life of the middle-class American worker. Here “Little Boxes” aren’t the cages of the workers, they’re the castles of their rulers.

Throughout the album there’s Jara’s powerful voice and truly beautiful guitar playing. What this record does not reflect is Jara’s passionate interest in folklore. The traditional Peruvian number “A la molina no voy más” (I Won’t Go Back to the Mill) suggests some of this, but it never moves very far beyond the tune’s political messaging. We are fortunate that Jara’s final album, Canto por travesura, full of traditional southern Chilean folk songs, was released a mere 10 days before his death.

The polemical force of his art should not — could not — be enough to preserve his memory. Nor the brutality of his death, nor the violence of the times in which he lived. As Jara wrote in his last poem, smuggled out of the stadium before his death, “How hard it is to sing when I must sing of horror.” Víctor Jara, child of peasants and former seminary student, was no mere “Marxist singer” — he was truly a lover of his people. Today the Estadio Chile is called the Estadio Víctor Jara.

– Jeremy Ray Jewell

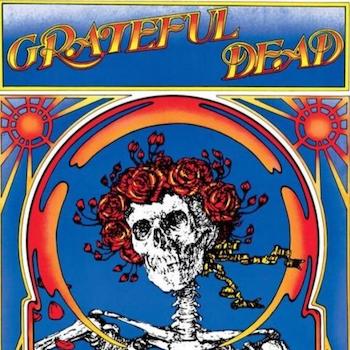

Grateful Dead – Grateful Dead (Warner Bros)

Whenever someone unfamiliar with the music of the Grateful Dead asks me for a good place to begin exploring, I inevitably recommend the band’s self-titled live album from 1971.

Whenever someone unfamiliar with the music of the Grateful Dead asks me for a good place to begin exploring, I inevitably recommend the band’s self-titled live album from 1971.

It’s not that Grateful Dead is the band’s best album (it arrived on the heels of two superior records, Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty) or even the best live album (Live/Dead from 1969 and Europe ’72 released a year later are both far more essential).

Still, Grateful Dead functions like a greatest hits album — except there aren’t any hits. In place of bona fide chart-toppers, we get a band displaying its ability and desire to be a melting pot of traditions and distiller of a distinct sound.

Released as a double album, Grateful Dead stitches together primal rock ’n’ roll, rustic country, both improvisational and balladic jazz, populist folk, and swaggering blues into a cohesive and compelling package that is nothing other than Grateful Dead music; either you’ll like this stuff, or you won’t.

Grateful Dead is also imbued with lore central to the band’s mythology. Alton Kelley’s cover art of a skeleton wearing a crown of roses is iconic. (The image has spawned the release’s “unofficial” name, Skull and Roses.) The band itself wanted to call the record Skullfuck, a suggestion that turned execs at Warner Bros. Records apoplectic.

Grateful Dead comes from concerts played in April 1971 at New York City’s Fillmore East and the Manhattan Center, in addition to a frenetic “Johnny B. Goode” performed in March at the band’s San Francisco home base of the Winterland Ballroom. The band at this point consisted of guitarists Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir, bassist Phil Lesh, drummer Bill Kreutzmann, and singer/keyboard player Ron “Pigpen” McKernan (with Merl Saunders later overdubbing organ parts).

Grateful Dead opens with the swirling psychedelic groove of “Bertha,” one of the many then-new compositions from Garcia and lyricist Robert Hunter. Garcia/Hunter also yield the haunting ballad “Wharf Rat.” Weir debuts “Playing in the Band,” here in an embryonic form at four-and-a-half minutes; within a year this would become an anthem, a 20-plus-minute concert epic. For a psychedelic peak, the band revisits Weir’s “The Other One” from 1968’s Anthem of the Sun.

The rest of Grateful Dead features cover tunes that convey the band’s broad embrace of American roots music. Pigpen serves up juicy blues with the Jimmy Reed hit “Big Boss Man.” Janis Joplin’s definitive take on Kris Kristofferson’s “Me and Bobby McGee” arrived in January 1971, yet the Dead’s version on this record is sturdy in its own right. The band mines additional country gems with Merle Haggard’s “Mama Tried” and the murderous cowboy tale “Me and My Uncle.” Driven by Garcia’s sinewy guitar work, “Big Railroad Blues” and the pairing of “Not Fade Away” and “Going Down the Road Feeling Bad” upend the band’s image of being (strictly) psychedelic noodlers.

Grateful Dead was for a time the band’s best-selling album, ironically knocked from that perch by a real greatest hits album, Skeletons from the Closet.

– Scott McLennan

E Pluribus Funk – Grand Funk Railroad (Capitol)

In late 1971, Grand Funk Railroad released the song “People, Let’s Stop the War.” Less than four years later, the Vietnam War ended. A coincidence? We think not.

In late 1971, Grand Funk Railroad released the song “People, Let’s Stop the War.” Less than four years later, the Vietnam War ended. A coincidence? We think not.

History tends to remember Grand Funk as the crudest superstar hard-rock band of them all, but their 1971 album proves they were something more. They were the U2 of their time: they not only believed a rock band could change the world, but that it had the responsibility to do so. Made at the height of their popularity, E Pluribus Funk plays like a rally set to music.

All but two of the songs are topical, and they’re not all about Vietnam: “Save the Land” was one of the first rock tunes about ecology, and “Loneliness” — a musical sequel to their epic ballad “I’m Your Captain” — takes on overpopulation. Lyrically, main singer/writer/guitarist Mark Farner came up with a workable mix of cogent arguments and old-fashioned rabble-rousing. Try arguing with this: “If we had a President who did just what he said/The country would be just alright and no one would be dead/From fighting in a war that causes big men to get rich/There’s money in them war machines — Now ain’t this a bitch!”

Grand Funk also knew that you don’t change the world with songs nobody remembers. So the songs on E Pluribus are loaded with hooks and riffs, while Farner’s vocals are rooted in Detroit soul. Side one builds intensity until its finale, “I Come Tumblin’,” sounds downright apocalyptic. Overall, they were never that far in music or philosophy from their fellow Detroit radicals, the now-sainted MC5. Grand Funk, however, committed the critical sin of being enormously popular. Just a few months before the release of E Pluribus, they became the second band ever to headline Shea Stadium.

The Shea event was instigated by their manager/producer Terry Knight, who was one of the main reasons critics hated the band. An old-school, music-biz huckster, Knight undercut the band’s importance by trying to turn them into demigods (his liner notes on the compilation album Mark, Don & Mel are a masterpiece of bullshit). His production on the first couple albums is indeed crude: No amount of remixing can keep the drums on their debut, On Time, from sounding like cardboard boxes. The band finally sacked him just after E Pluribus, but by this time he knew what he was doing. And the production here is great: the bass has amazing presence, the orchestral finale of “Loneliness” sounds massive, and that odd percussive sound he runs through “Upsetter” — probably a scraped guitar played backwards — gives it some nice propulsion.

For better or worse, Grand Funk redeemed themselves critically in later years. With Knight out of the picture, they hired producers (starting with Todd Rundgren) who proved they could really sing and play with some finesse. Indeed their last album — produced by Frank Zappa of all people — was called Good Singin’ Good Playin’. But they largely lost their sense of mission in the process, becoming something of a party band; it’s sad that they’re now remembered mainly for a song (“We’re An American Band”) that Kiss could have done. Nobody needed to defend the performances on E Pluribus Funk, but more importantly, it was also good revolutionizin’.

– Brett Milano

Fragile – Yes (Atlantic)

Yes brandished positivity in 1971, releasing its third and fourth albums to become creative and commercial forebears of that era’s progressive rock movement.

Yes brandished positivity in 1971, releasing its third and fourth albums to become creative and commercial forebears of that era’s progressive rock movement.

Co-founders Jon Anderson (lead vocals) and Chris Squire (bass, vocals) were fans of Simon & Garfunkel, who were interested in challenging instrumentation. In February 1971, The Yes Album introduced the feisty, versatile guitarist Steve Howe, who capped the three-part harmonies of the British quintet’s first Top 40 hit, “Your Move.” It began with the a cappella broadside “I’ve seen all good people turn their heads each day, so satisfied I’m on my way.”

But it was the imaginative November release Fragile that crystallized the group’s sense of grace and space, complemented by cover art of a primitive airship over a tiny planet (artist Roger Dean’s fantasy landscapes grew synonymous with Yes over subsequent releases). Fragile also boasted new keyboardist Rick Wakeman, who embraced electronic toys like the mellotron and Minimoog to further round out the instrumental virtuosity that members refined together and separately.

Howe broadened the album with acoustic touches, from the ringing harmonics that announce megahit “Roundabout” to his lithe flamenco solo recital “Mood for a Day.” The full band only arranged and performed four tracks. The other five were individual-helmed pieces that spanned Wakeman’s classical adaptation “Cans and Brahms,” drummer Bill Bruford’s twitchy “Five Per Cent for Nothing” (both trifles next to those players’ contributions elsewhere), and Squire’s unique layered-bass excursion “The Fish (Schindleria Praematurus),” which rises from the brittle guitar coils of melodic charmer “Long Distance Runaround.” Anderson, whose choirboy voice provided calm at the center of Yes’s musical storms, sang three different choruses that overlap in his rounds-styled “We Have Heaven.”

That piece closes with the sound of a slammed door and rushed footsteps (this being the heyday of panned effects for maximum headphone listening) that fade into a wind-and-thunder segue to “South Side of the Sky.” That knotty rocker, riddled with Howe’s electric guitar, showcases Wakeman in a winding piano interlude iced by haunting cross-harmonies over Bruford’s slithery undertow.

Wakeman also unleashes the spiky organ solo that levitates the overexposed “Roundabout” (over Bruford’s trademark snare pop) and alternates spooky piano and mellotron in the underrecognized “Heart of the Sunrise.” That dynamic 11-minute closer serves as Fragile’s masterpiece — and a template for suite-like future album sides “Close to the Edge,” “The Gates of Delirium,” and the bloated Tales of Topographic Oceans. (1972’s Close to the Edge may be Yes’s best album, yet Fragile offers the band’s best-sounding record with trusty co-producer/engineer Eddy Offord.) “Heart of the Sunrise” drops a delicate dance between Squire’s stealthy lead bass and Bruford’s crisply accented drums amid tornadic drag-races where Squire and Howe rip in tandem, plus one of Anderson’s most sensitive and passionate vocals.

Then a door opens to a closing reprise of “We Have Heaven.” That’s the kind of ceiling that Yes aspired to behind the doors of a London studio. Fragile floats a rare confluence of interlocking parts, personality, and perfection.

– Paul Robicheau

Tagged: Allen Michie, Brett Milano, E Pluribus Funk, El derecho de vivir en paz, Fragile, Grand Funk Railroad, Grateful Dead, John Lee Hooker and Canned Heat, Jon Garelick, Paul Robicheau, Scott McLennan, Víctor Jara