Film Review: “Show Me the Picture: The Story of Jim Marshall” – (Leica and Drugs and Rock ’n’ Roll)

By Ed Symkus

Jim Marshall fought off all sorts of personal demons while also managing to be in the right place at the right time to get some iconic music photos.

Show Me the Picture: The Story of Jim Marshall is available on Apple TV+ and iTunes.

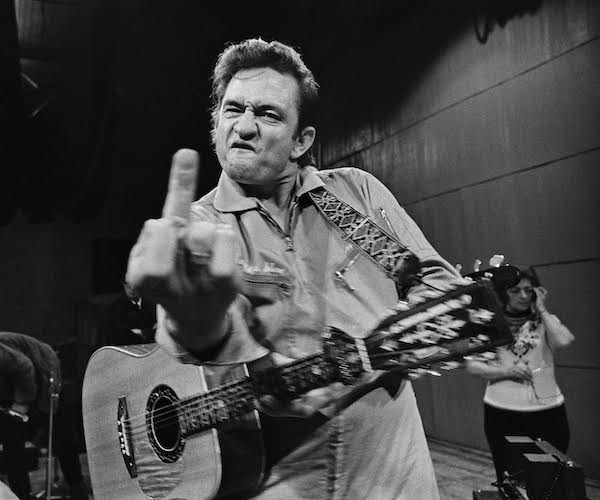

Johnny Cash photographed at San Quentin, CA. © Jim Marshall Photography LLC

You have undoubtedly seen the work of music photographer Jim Marshall. His work ranges from the album covers of The Allman Brothers Band at Fillmore East and the John Coltrane Quartet’s Ballads to Jimi Hendrix, on his knees before his flaming Stratocaster at the Monterey Pop Festival, and Johnny Cash defiantly extending a middle finger to Marshall’s camera at San Quentin State Prison.

The documentary Show Me the Picture: The Story of Jim Marshall displays lot of his photos and — via archival footage and interviews with Marshall (1936-2010), as well as with memories from friends, admirers, and folks who worked with him — delves into what made the man tick. Unfortunately, this talented, troubled, work-your-ass-off-guy ticked like a bomb.

One of the first things heard in the film’s opening voice-over by his former assistant Amelia Davis is that Marshall had a cocaine habit that started in the late-’60s or early-’70s. In storytelling, that’s called foreshadowing. Davis, who now runs Marshall’s photo archive, goes on to talk about his death — in his sleep — at a New York hotel room, smiling at the memory and saying, “He died like a fuckin’ rock star.”

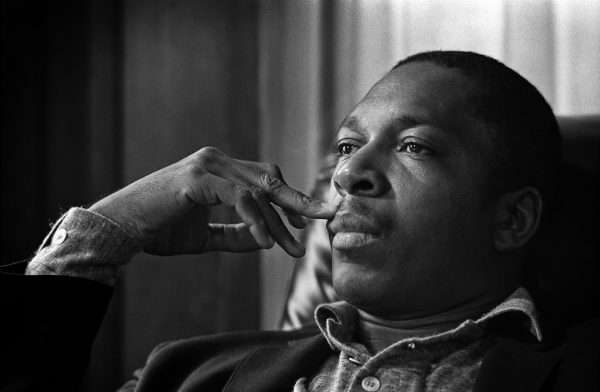

John Coltrane. © Jim Marshall Photography LLC

Marshall got his first Brownie camera at age eight or nine, when he was growing up in San Francisco, and he cut his professional teeth in photographing jazz artists. Among the abundance of photos on display in the film are his coverage of the Monterey Jazz Festival, as well as an intimate portrait of John Coltrane, sitting back, lost in thought, and a delightful one of Thelonious Monk, with his wife and kids, in their New York home.

He got plenty of work in that world, but he found fame after he started pointing his lens at the rock community in San Francisco. Jefferson Airplane guitarist Jorma Kaukonen says, “Jim was one of the first guys that showed up with a camera and wanted to take pictures of us.”

There are the obligatory stories of a tough childhood. He was brought up by his mom; his dad was rarely around. And there are ample thoughts about him in interviews. Music journalist Joel Selvin says, “His photos have the feeling that nobody else is in the room but the subject.” Photographer and friend Bruce Talamon says, “The stuff that Jim got, you’ll never see that again.” Amelia Davis remembers him as “such an intense person; he could be the biggest asshole, and then the next minute, he could be the sweetest guy in the world.” Actor Michael Douglas, who met and got to know Marshall when he was taking photos on the set of The Streets of San Francisco, says, “There was a softness and compassion about him, and how he treated his friends. But you did not want to be on the wrong side of Jim Marshall.”

Jimi Hendrix sound check, Monterey Pop Festival, 1967. © Jim Marshall Photography LLC

But it’s Marshall’s own words, from an interview in his San Francisco apartment in 2006, and on an audiotape of a 1978 radio interview, both of which are peppered throughout the film, that reveal the most about him.

At a calm moment, he says, “I think a lot of photographers abuse the camera and abuse what they do. Artists let you into their life as a trust, and I feel that to violate that trust is criminal.”

When a bit of frustration is lurking in his psyche, he says, “I prefer just to hang out and shoot as a photojournalist. I want total access. If they want me there, they should respect my judgment and taste and integrity, and just let me take my fuckin’ pictures.”

In one of many interview segments with Michelle Margetts, a journalist and former girlfriend, she recalls when she chose him as a subject for a magazine writing class in 1984. She mentions that he was already famous as a photographer, and that “he was just released from prison.” More foreshadowing.

The incidents leading up to him doing time are eventually explained, but Marshall casually alludes to them early on with, “I’ve always liked cars, guns, and cameras. Cars and guns have gotten me in trouble. Cameras haven’t.”

The film turns out to be as much about the man as about his photos. Most of those speak for themselves, but there are a few examples of how he got them. When circumstances allowed it, he chose to get physically close to his subjects, rather than use a long lens. He found that he could exploit this closer access by going the simpatico route. Maybe it was to get a better picture, maybe it was because he enjoyed it, but when asked about covering the Rolling Stones on their 1972 tour, he says, “I probably did more coke than they did.” At the soundcheck for his longtime pal Johnny Cash’s San Quentin concert, he said to Cash, “Johnny, let’s do a shot for the warden.” The result was the famous finger photo.

And they keep on comin’. Director Alfred George Bailey fills the film with Marshall’s shots of Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, the Beatles, Cream, the Who, Miles Davis, Janis Joplin, and many others.

The Story of Jim Marshall is tidily summed up by Michael Douglas. “His pictures are immortal,” he says. “The beauty of what he did is living way past his life.”

Ed Symkus has been reviewing films and writing about the arts since 1975. A Boston native and Emerson College graduate, he co-wrote the book Wrestle Radio, USA: Grapplers Speak, went to Woodstock, collects novels by Harry Crews, Sax Rohmer, and John Wyndham, and has visited the Outer Hebrides, the Lofoten Islands, Anglesey, Mykonos, the Azores, Catalina, Kangaroo Island, and the Isle of Capri with his wife Lisa.

His favorite movie is And Now My Love. His least favorite is Liquid Sky, which he is convinced gave him the flu. He can be seen for five seconds in The Witches of Eastwick, staring right at the camera, just like the assistant director told him not to do.