Film Reviews: At the NYFF — Haynes’s “The Velvet Underground,” Dumont’s “France,” and Peleshian’s “Nature”

By David D’Arcy

Reviews of Todd Haynes’s documentary The Velvet Underground, Bruno Dumont’s France, a satire-drama about the news industry, and Nature, Artavazd Peleshian’s graceful parade of natural disasters.

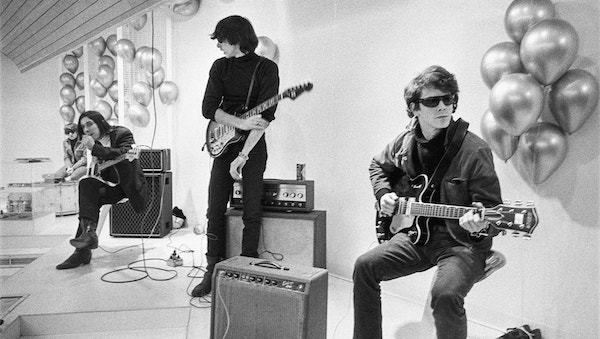

Moe Tucker, John Cale, Sterling Morrison, and Lou Reed from the documentary The Velvet Underground. (Nat Finkelstein Estate/Apple TV+

I’ve never been a fan of the Velvet Underground, but Todd Haynes’s documentary, filmed during the pandemic and which just premiered at the New York Film Festival (in theaters and streaming on October 15) is an admirer’s imaginative tribute, with cinematic flourishes and enough archival material to surprise even the diehards. There’s more video from that time than anyone would have expected.

Film as collage is the approach Haynes uses here, and it serves him and his subject well. The constant shuffling of photographs and concert programs, a recurrent motif in monochrome, evokes both the brevity of youth and the serendipity of forming the band. Like so many rock groups, the Velvet Underground stumbled onto the right combination of musicians for its moment. Yet, unlike so many bands, its moment has had an ever-expanding afterlife for the group’s fans.

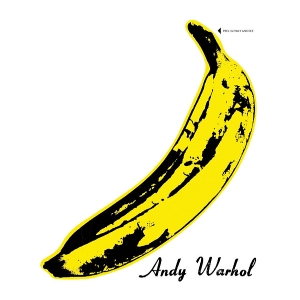

Kinetic and kaleidoscopic, Haynes’s doc may do for the band’s memory what Andy Warhol did for the group’s launch when the artist designed the cover of their first album, released in 1967 — a single silk-screened yellow banana that unzipped to reveal a pink banana. (If that foreshadows the cover of Sticky Fingers, the Rolling Stones’ album of 1971, so be it.) To my prejudiced ear, the band sounds as good here as they ever sounded — far better than I ever remembered in the mournful and weary “All Tomorrow’s Parties” that closes out the credits. Haynes’s rapid-fire editing of images reminds us that the ground was always shifting beneath the band members from 1965 to 1970. Concentrating on those halcyon years, the doc can’t help but leave out interesting parts of the story. Fans, agog with what is on the screen, probably won’t mind.

The crucible for this New York band was 56 Ludlow Street, when the Lower East Side was rough and anything but chic. New York was not a nourishing place for rock groups. The Lovin’ Spoonful was a New York band. So were Dion and the Belmonts. In comparison, how many Boston bands from that period can you name? The punk era, filled with groups inspired by the Velvet Underground, would be a much more fertile time for rockers in New York.

And New York would define the Velvets’ deadpan, languorous, and arty identity. On their first tour dates in California, thought by many to be the birthplace if not the heart of the music scene, band members felt out of place. “Flowers in your hair? Fuck you,” says drummer Moe Tucker, “We hated hippies.”

And New York would define the Velvets’ deadpan, languorous, and arty identity. On their first tour dates in California, thought by many to be the birthplace if not the heart of the music scene, band members felt out of place. “Flowers in your hair? Fuck you,” says drummer Moe Tucker, “We hated hippies.”

The documentary’s most eloquent voice comes from John Cale (who survives, along with Tucker), whose recollections of growing up in Wales, where his first language was Welsh, are a film within this film. In his gentle and resonant voice, Cale recalls his childhood and his training playing classical music on the viola as Haynes’s camera passes gently over family photographs. New York was another planet for the young Welshman. It was at 56 Ludlow Street that Cale connected with Lou Reed, the Brooklyn-born child of a Long Island upbringing, who had his eyes set on stardom. There the band took shape.

And then there was Warhol, who created the banana cover for the band’s first album. With surprising modesty, Cale admits that they didn’t expect much attention. Warhol and Nico, the German singer who fronted the band, were the only reason people noticed, Cale said. Anyone who has heard Nico knows that the statuesque blonde was more of a presence than a singer. Still, band members insist that she was crucial to their escaping anonymity.

If viewers are looking for glam, this may not be the right film. Try Haynes’s The Velvet Goldmine instead. This portrait of the Velvet Underground reveals them to be hardworking (albeit contrarian) musicians, with a discipline that immediately set them apart from the swarm of other wannabe superstars who lounged at Warhol’s Factory.

As with so many bands, the seams eventually showed. The group emerged with an experimental sound, coming mostly from Cale and the influence of LaMonte Young, a pioneer of minimalism known for his work with sustained tones. It was an odd evolution: the combination of Cale’s viola and Reed’s dirge-inspired guitar wilted into something that sounded more and more like a rock band — and an ordinary one at that. Bassist Sterling Morrison, who hated playing bass, went off to study medieval literature. Warhol, never allergic to the marketplace, encouraged the shift from experimental to commercial (and would eventually be fired by Reed). Reed, the lead singer and songwriter, felt less and less of a need for Cale’s imaginative talent. The Velvet Underground lost the thoughtful Welshman and, when Reed left, eventually lost its reason for being, even though Doug Yuel kept the group going after that. Haynes doesn’t trace Reed’s long solo career. His fans know that territory well enough.

Among Haynes’s many visual tricks is the split-screen cutting, with a finesse that can be missed if you blink. At times, the screen is divided into into four quadrants, each with a head shot of one of the band’s four members — Reed, Cale, Morrison, and Tucker. The composition calls to mind the cover of the Beatles’ album Let It Be. Is Haynes suggesting that the Velvet Underground were as influential or important or immortal as the Fab Four? If so, he would not be alone.

Lea Séydoux as the celebrity reporter in France.

Also at NYFF was France, Bruno Dumont’s satire-drama about an ambitious television reporter, France de Meurs (Lea Séydoux), who challenges French president Emmanuel Macron at press events. France also travels to war zones where she dodges bullets and speaks, via staged segments that she sets up with her crew, on camera to armed men in terrorist groups. Yes, fake news.

For France, the reporter, fake journalism makes for a real and lucrative career, a warning from Dumont that this might be the route his country is taking. (Note – In France, France is a common name for women. And the name France de Meurs also suggests a play on words – the manners of France or les moeurs de France – that evokes deception in the zeitgeist.) The director also seems to be suggesting that his country is being Americanized, as France puts herself at the center of sensational news stories that she stage-manages. After a car accident, she flees to luxurious rehab at a hotel in the Alps, where she meets a young man who — God forbid — has never heard of her. She has trouble believing this, and it turns out that she was right to be skeptical.

Of course, things fall apart for Dumont’s heroine, who is also guilty of neglecting her husband and resentful son. If that weren’t shameful enough, she collects bad art, which is spotlit on the black walls of her home.

NYFF was short on laughs this year. Dumont is an odd filmmaker to fill the breach, since he made his name with mournful films about sad lives, with nonprofessional actors, in the bleak north of France. The director turned a corner with his surprisingly funny series P’tit Qin Qin (“Li’l Qin Qin”) in 2014. France continues on that path, with some welcome comedy added to the melodrama.

Frankly, his fears for the integrity for the French media, based on the self-involvement of France de Meurs, comes off as exaggerated, perhaps for the sake of point-scoring. But it pales before the reality of self-promotion. To get a sense of the dizzying depths of self-involvement look at American media stars, one need only watch FOX News or read the excerpts from Katie Couric’s memoir Going There that have been published in the tabloids. Check out the response to the book from the Couric family’s former nanny, which ran in the Daily Mail. Dumont may be worried, but the grotesquery of American media and the vanity of some of its celebrities still sets the bar for megalomania.

A still from Artavazd Peleshian’s Nature.

A film at NYFF not be be missed when it receives wider release is Nature by the Armenian veteran director Artavazd Peleshian. Its title is a little misleading. Nature observes natural disaster — volcanic eruptions, floods, tidal waves, fires, lava flows, cyclones, and probably an earthquake or two.

Peleshian is the definition of old school. The Armenian director Sergei Parajanov called him one of the authentic geniuses of cinema. Now 83, he worked in Soviet cinema for decades. If you couldn’t be monumental there, where could you be monumental? Somehow he found a benefactor in the Fondation Cartier in Paris, which funded this film, his first in 30 years. So we have a monumental silent film with black-and-white footage of natural disasters funded by a foundation established by a jewelry company.

There are no gems to admire in Nature, but a graceful view of the earth from the sky, followed by relentless scenes of cataclysm. Peleshian is known for his experiments with perspective. Here he becomes the curator of scenes of devastation, accompanying them with classical music, from Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis to selections from Mozart and Shostakovich. After exploding volcanoes come tidal waves, as we watch tiny human figures swept across the frame. Great music does not make these scenes any easier to watch.

Images of disaster are all over YouTube. In Nature, Peleshian reminds his audience that upheavals can be spectacular, hypnotic, and seductive. His film begs for a grim sequel of disasters created by human intervention. Just imagine watching that.

David D’Arcy, who lives in New York, writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: Artavazd Peleshian, Bruno Dumont, David D'Arcy, France, Lou Reed, nature, New York Film Festival, The Velvet Underground