Book Review: A Mother Lode of Imagery and Information

By Jacqueline Houton

This eye-opening collection of photo-essays, essays, and interviews offers a kaleidoscopic view of a subject that is too often hidden, treated as a private concern rather than one of vital public interest.

Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births by Michelle Millar Fisher and Amber Winick. The MIT Press, 344 pages, $44.95.

For the past six months, I’ve been dutifully chewing my prenatal gummy vitamins every morning, but only recently did I learn that I should be raising my glass of OJ to Lucy Wills, the young British doctor who fed Marmite to a malnourished monkey nearly a century ago and figured out that the folate it contained was beneficial for pregnant women, too.

Wills’s story is one of many in the eye-opening new book Designing Motherhood: Things That Make and Break Our Births. Birth may be one of the few experiences shared by every person on the planet, but the material culture of human reproduction has often been overlooked. Michelle Millar Fisher, a curator of contemporary decorative arts at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, and Amber Winick, a writer, design historian, and mother of three, offer a corrective with this collection of essays, photo-essays, and interviews. Like the Instagram account the authors have used to share their research over the last few years, it’s highly visual, filled with many striking full-bleed images, but this is no coffee table book — it’s a tome thick with footnotes, dealing with matters of life and death, fascinating and unsettling in equal measure.

Divided into four sections — reproduction, pregnancy, birth, and postpartum — the book explores more than eighty designs. It plumbs the hidden histories of familiar products, like the menstrual cup (whose first commercial model was patented by a Broadway actress), the baby monitor (developed in the aftermath of the Lindbergh kidnapping), and the umbrella stroller (dreamed up by an aeronautical designer for his grandkids). There are looks at maternity wear, from the Indian saris that have accommodated changing bodies for centuries to the tie-waist skirt famously worn on I Love Lucy during Lucille Ball’s unprecedently public pregnancy. There’s graphic design and print media — ads, magazine covers, activist signage, propaganda posters, and early incarnations of Our Bodies, Ourselves, which began as a handwritten zine passed out after a women’s liberation conference in Boston in 1969; today it’s a 900-pager printed in 30-plus languages. And there are deep dives into myriad medical devices (forceps, speculums, stirrups, incubators) and drugs (including both Clomid, a boon for couples struggling with infertility, and Thalidomide, a cause of devastating birth defects marketed as a cure for morning sickness by the very same pharmaceutical company less than a decade earlier).

Indeed, much of the medical content is harrowing. Many innovations were developed without the consent of the people they were tested on. The speculum we know today was fine-tuned by Dr. J. Marion Sims, dubbed the father of modern gynecology, who performed experimental fistula surgeries on enslaved Black women without anesthesia. More than a century later, the game-changing contraceptive Enovid was tested on psychiatric patients at Worcester State Hospital, as well as on female medical students in Puerto Rico who were told that participating in the clinical trial and submitting to pelvic exams was a required part of their coursework. Too often, designs prioritized the convenience of (mostly male) doctors rather than the well-being of patients, as in the case of the Dalkon Shield, a contraceptive device implanted in 2.5 million American women in the ’70s before an outcry led the FDA to suspend sales and start monitoring medical devices. Its multifilament wick, while handy for the doctor removing it, introduced bacteria into the womb and caused pelvic inflammatory disease in many, including pioneering reproductive justice activist and interview subject Loretta J. Ross, who fell into a coma and awoke to learn she’d undergone a total hysterectomy at age 23. The appalling facts are hardly confined to history: Maternal mortality in the US has doubled since 1991 and, as law professor Khiara Bridges points out in another interview, Black women are three to four times more likely to die during pregnancy or childbirth than white women, a disparity that persists across income levels.

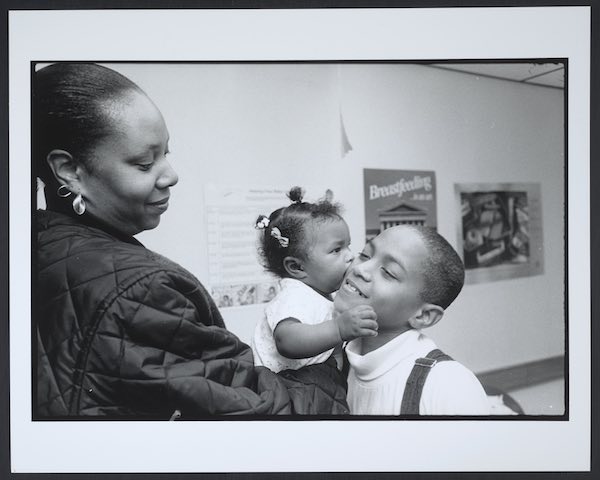

Maternity Care Coalition staff serving their clients in Philadelphia, 1980s. Courtesy of MCC and the University of Pennsylvania Library Archives.

But Designing Motherhood highlights many instances of ingenuity, possibility, and pleasure too. An interview with Stephanie Tillman, a Chicago midwife who avoids the use of stirrups in her practice, is accompanied by illustrations from Table Manners, a guide to comfortable positions for pelvic exams for patients with disabilities — a reminder that products and practices that account for the needs of diverse bodies mean better designs for everybody. An essay on Grace Jones’s avant-garde maternity costumes — including a geometric mega-dress that might be fashion history’s most flamboyant form of camouflage — delivers a jolt of joy (and left me wishing I could travel back in time to score an invite to her baby shower, co-hosted by Debbie Harry and Andy Warhol at the Paradise Garage disco). And I wanted to cheer as I read about the moxie of underdog innovator Meg Crane, the graphic designer who pushed her reluctant employers to develop a home version of the pregnancy test they sold to doctors. Left out of the design process, she created her own prototype and deposited it next to the frilly official prototypes from an outside agency hired by the pharmaceutical company. The agency director, waltzing in late to the meeting, declared Crane’s sleek design to be the obvious choice (and later became her studio partner and husband).

Throughout, the book makes a compelling case for the importance of designing better objects for menstruators, pregnant people, and babies, but it also acknowledges that design is not enough; we desperately need better policy, too. Consider the breast pump, an early prototype of which was adapted from a bloodletting apparatus in the 1840s. Eighty years later, an improved model devised by dairy engineer Edward Lasker and pediatrician Isaac Abt was still noisy, unwieldy, and painful to use. Progress came in the ’50s, when civil engineer Einar Egnell had the bright idea to create a design based on observations of human — rather than bovine — anatomy, working closely with nurse Sister Maja Kindberg, who became the model’s namesake, to test designs with new mothers at a Stockholm maternity hospital. But by 2014, the year of the first Make the Breast Pump Not Suck! Hackathon at MIT, the options on the market still left much to be desired. Yet as MIT Media Lab designer and researcher Alexis Hope writes in her essay, the Hackathon’s founders ultimately concluded that no technological innovation can make up for the fact that we live in a country that pushes postpartum people back to work too early. The US remains the only industrialized nation without mandated paid family leave, and a full quarter of Americans who give birth return to work within two weeks. We can and should expect better from our systems — a truth driven home by Gordon Parks’s series of photographs documenting the federally subsidized childcare program that operated during World War II, mementos of a time when the US government briefly decided that supporting working mothers was a matter of national import.

Dalkon Shield (far left) intrauterine device used in the early 1970s and 1980s and produced by the A.H. Robins Company in the US. It caused an array of severe injuries, including pelvic infection, infertility, unintended pregnancy, and death. Eventually the US Food and Drug Administration banned the device. Image courtesy the Mütter Museum.

Fisher and Winick, both white women in their late thirties, incorporate insights from nearly sixty other contributors whose diverse perspectives buoy the book. The end result is a kaleidoscopic view of a subject that is too often hidden, treated as a private concern rather than one of vital public interest. Expansive in its definition of design and dense with information, Designing Motherhood is the kind of resource most will not read cover to cover, but dip into here and there—and then find themselves suddenly drawn in deep by a story or an image. It’s a read that’s relevant for anybody who’s been born.

Jacqueline Houton is an editor and writer based in Cambridge. A former editor of The Improper Bostonian and managing editor of The Phoenix and STUFF magazine (RIP x3), she currently copyedits kids’ and YA books by day and serves as senior editor at Boston Art Review. Her writing has appeared in Big Red & Shiny, Bitch magazine, Boston magazine, Pangyrus, Publishers Weekly, and other publications.