Jazz Album Review: “Chick Corea Akoustic Band Live” — A High-Spirited Reunion

By Michael Ullman

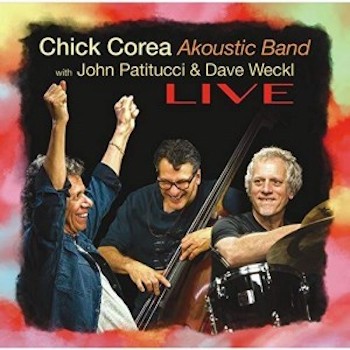

Chick Corea Akoustic Band — Live with John Patitucci and Dave Weckl. (Concord Records)

A judicious mix of jazz classics, standards, and Corea compositions, Live is a blast.

In my earliest years going to jazz clubs, pianist Chick Corea was pleasingly omnipresent. I first heard him with Herbie Mann, who introduced him as Armando Corea. I don’t remember him standing out among Mann’s crowd. Subsequently, the pianist was part of one of the most extraordinary afternoons of music in my experience. The site was Lennie’s on the Turnpike, probably in the summer of 1967. Lennie was a true music lover. He said that he had always wanted to present Duke Ellington, so he did, taking out the first rows of tables to fit Duke’s Steinway grand. Clearly he lost money on the gig. The solo piano afternoon was obviously a pet project. On my memorable date, Lennie presented solo sets by three great pianists: Earl Hines, Jaki Byard, and finally Chick Corea, who was introduced by critic Stanley Dance as an up-and-coming pianist. He had already distinguished himself on records that I owned featuring vibist Dave Pike and flutist Hubert Laws along with, most strikingly, trumpeter Blue Mitchell, who recorded Chick’s tunes, including the now celebrated “Tones for Joan’s Bones.” At this point, Corea was beginning to be seen as a composer as well as a remarkably skilled, and flexible, pianist.

Still, although most of the audience members that afternoon were Hines fans, Corea managed to impress most of us. He had come up fast in the early and middle ’60s. He had arrived, with certainty, when I started collecting his records, including the remarkable trio album Now He Sings, Now He Sobs (1968). Featuring Miroslav Vitous and Roy Haynes, this Blue Note record, with its super-hip compositions and vital, alert interactions among its three musicians, took what was seen as the next step in jazz trio performance. Although he was already playing with a trio, I next saw Corea with Miles Davis, as part of what has come to be called the “lost quintet.” (Again, this was at Lennie’s.) Amid that remarkable entourage, Corea and Dave Holland and Jack DeJohnette seemed to be playing against Davis as well as with him: Corea would take one of Davis’s tunes and go out with it, abandoning not just its melody but its chord changes and characteristic rhythms. At times, the band members seemed to be afloat on their own islands. Corea continued with Miles for a while. In 1970, a little before Davis’s Bitches Brew was released, I heard the pianist play with Miles and John McLaughlin in Ann Arbor’s Hill Auditorium.

Meanwhile Corea was adventuring on his own and with members of the avant-garde. He was on Marion Brown’s Afternoon of a Georgia Faun (1970), and started a quartet with Holland, Anthony Braxton, and Barry Altschul. He called the group Circle. In 1971, the pianist made the adventurous trio album A.R.C. with Holland and Altschul. Corea was nothing if not adaptable: in 1972, he was the pianist on Stan Getz’s celebrated Captain Marvel. Corea broke up Circle explicitly because he wanted to communicate with a broader audience. Often, in the early ’70s, that desire to garner more ears led to what hard core jazz fans called “selling out.” Not with Corea. When I next saw him, at Baker’s Keyboard Lounge in Detroit, he was leading the so-called Return to Forever band, which had registered a hit with its “La Fiesta” (recorded on ECM). The group featured Joe Farrell on saxes, Airto Moreira on percussion, and Stanley Clarke on bass, with Flora Purim contributing occasional vocals. Remarkably, the new band — with its quasi-Brazilian repertoire — was as pleasing musically as it was popular.

The Chick Corea Akoustic Band: (l to r) Chick Corea, John Patitucci, and Dave Weckl.

Corea’s death on February 9, 2021 was a shock. Looking over his huge recorded legacy, I am especially a fan of his trio music. So the new double CD Chick Corea Akoustic Band — Live is an unexpected joy. The players are all old friends. In the mid-’80s Corea recruited bassist John Patitucci and drummer Dave Weckl for his electric band. Recorded decades later, in St. Petersburg, FL, in January 2018, Live is a high-spirited reunion gig, a gathering of virtuosos with a long musical history together. It provided a perfect opportunity for Corea to revel in his idiosyncratic mix of virtuosity and whimsy. One element remained the same throughout his long career — Corea always sounds like he’s having a good time.

In the album’s notes, Corea explained how Live was made:

This double CD is the result of a 2-day whirlwind … a quick rehearsal and 2 shows the next evening. I grew up in a tradition of play-now-first-takes. The idea of playing a piece over and over until it’s “just right” was never part of my makeup. I always experienced the 1st take as the magic one. It may have a few missed notes, but it always had that tingle that makes performance exciting…. Well, I threw some new arrangements together and revisited some of the things we played in the past, rehearsed for a few hours so we could end together … then threw down at the gig. Ok, a few missed notes, but we got the Tingle … so I am really pleased.

He should have been overjoyed. A judicious mix of jazz classics, standards, and Corea compositions, Live is a blast. There are two versions of Corea’s “Humpty Dumpty,” a favorite piece that the pianist recorded in various lineups: in duet with Hiromi, in a trio with Christian McBride, and with a larger group on his 1978 tribute to Lewis Carroll, The Mad Hatter. Corea may have worked out the endings of the tune with the trio, but in the introductions the pianist is as free as a bird. He kicks off both takes with a fast right-hand line, setting off a rapid and amusing conversation between his hands. The version from the first set quickly moves to the theme. In the second set, Corea begins similarly, but then goes further. At one point he plays a low chord and just holds it with the pedal. He recovers from that stupor, goes back into tempo, and then does it again. It’s a striking study in quicksilver phrases followed by sudden relaxations. After a couple of minutes you can hear Patitucci and Weckl laughing. They had no idea when they were supposed to come in. When they do, the piece turns into a swinger.

Corea introduces “Monk’s Mood” in a similarly active, varied style, one moment thumping and sighing the next. It’s a virtuoso performance that never forgets the shape of Thelonious Monk’s ballad. Of course, there is an Ellington tune here: “In a Sentimental Mood,” introduced via solo piano. After a couple of solo choruses, the rhythm section enters, Weckl splashing on cymbals, generating a different kind of sound. Patitucci reinforces Corea’s lines in uncanny fashion. Whenever the pianist plays a series of eighth-note chords, the bassist is right there to reinforce him. Corea expresses what he called his Spanish heart on “Rhumba Flamenco,” a tune from his 2001 Past, Present and Futures album. Here he starts off with a tremolo and a wild series of rapid lines before eventually embracing the flamenco melody. He stops and lets Patitucci fill in with some guitaresque lines while Weckl sounds almost threatening on percussion. The trio’s affection for the unexpected is highly gratifying; when the musicians finally touch down and play the melody in tempo it is a wonderful release.

Of course, there’s more on this double album, including a ravishing version of “Green Dolphin Street.” Patitucci supplies an exciting solo and Weckl’s drumming is remarkable here as well. The recording concludes with Corea’s “You’re Everything,” featuring his wife Gayle Moran Corea’s improvised vocal. There’s no sign of age or illness in these sprightly performances, only the invigorating fruits of gifted musicians playing with dazzling confidence and grace. Touchingly, Corea ends by telling his enraptured listeners, “Thanks for being part of our lives.”

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: Akoustic Band Live!, Chick Corea, Concord Records, Dave Wecki, John Patitucci