Rock Album Review: The Plastic Ono Band Celebrates 50 — A Nice Warm Cup of Instant Karma

By Matt Hanson

After having diagnosed the ails of modernity, screamed out his most deeply held traumas, and shrugged off his role in the biggest band ever, John Lennon is content to have a riverside cuddle under a tree in the sun with the woman he loves. Amen.

Yoko Ono and John Lennon at John Sinclair Freedom Rally, December, 1971. Photo: Wiki Common

First of all, let’s rid ourselves once and for all of the lazy sexist cliché that it was all Yoko’s fault. The Beatles broke up because first and foremost they were human beings, albeit extremely talented ones, and as any gigging musician will tell you, the grind (especially in a band as popular as The Beatles) wears your patience to a nub. Anyone who became the biggest in the world usually went nuts. Fame and fortune just ain’t what it’s cracked up to be. Henry James called it “the bitch goddess” while Lady Gaga preferred to call it “the fame monster.” These vengeful deities inevitably make it hard if not impossible to follow the original flicker of inspiration that got you there in the first place.

Maybe it’s due to a generational sea change, but I’ve gotten into more than a few arguments over the years over whether or not The Beatles were really just a bunch of phonies after all. One recent meme zinged that “The Beatles weren’t actually good; it was just the first time in history that women were allowed to be horny in public.” Point taken. But Elvis’s wriggling pelvis, just for a start, might like a word about that, and there were plenty of other examples. It’s far too easy to cock a skeptical eye at a media creation than to wonder what might be valuable or genuinely fun about it.

Maybe it’s the subversive thrill of rejecting the status quo, which to their credit Lennon and Harrison in particular were often more than happy to do. Sententious types claim to “hate” The Beatles, but they are usually willing to admit when pressed that they do like a couple of songs (usually, for some reason, it’s “Get Back”). Everyone is entitled to their own tastes, but hating on The Beatles reeks of conspicuous contrarianism. Still, when an actual Beatle says screw the Beatles — and quite loudly and unambiguously at that — then maybe it’s not as snarky a sentiment as it seems.

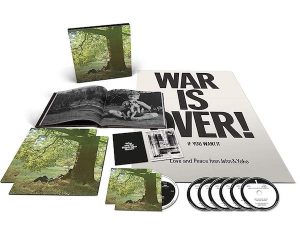

A cleansing act of breaking free, that’s how I see Plastic Ono Band, John Lennon’s first solo project, recorded 50 years ago and now given a handsome and extensive rerelease as a multi-disc boxed set. Every Beatle had plenty to get off their chest after what they’d signified musically and generationally had bitten the dust. Harrison stuffed All Things Must Past with great songs (it just might be the best Beatles solo record) and McCartney hatched the charming Ram from his bucolic Scottish retreat. For his part, Lennon got, as we now like to say, “woke.”

The term is apt, because it perfectly fits his sober-eyed post-Beatles mentality. Plastic Ono Band is an early example of what it looks like when artists step off the stage and get political. The Lennon of this period is more philosophical, more of an arch social critic, with a metric ton of long-held emotional trauma to unload. The Lennon of 1970 is like someone who has freshly graduated from college with a brilliant academic record who suddenly discovers how the other half lives and is disgusted by how little truth and beauty goes for in the so-called real world.

It’s fun to hear Lennon banter with himself and the rest of the band on “The Evolution Mixes.” He works through the different iterations of the songs, alternating between playfulness and self-criticism as he cracks dirty jokes and earnestly checks in with Yoko. The Plastic Ono Band drew quite a few public political and aesthetic lines in the sand, so hearing Lennon chortle at his own lyric about being “a victim of the insane,” and then breaking into ironically hysterical laughter at his own expense, is refreshing.

It’s fun to hear Lennon banter with himself and the rest of the band on “The Evolution Mixes.” He works through the different iterations of the songs, alternating between playfulness and self-criticism as he cracks dirty jokes and earnestly checks in with Yoko. The Plastic Ono Band drew quite a few public political and aesthetic lines in the sand, so hearing Lennon chortle at his own lyric about being “a victim of the insane,” and then breaking into ironically hysterical laughter at his own expense, is refreshing.

At least he’s self-aware enough to suspect his enthusiasm for the didactic. It’s one of the pitfalls of the newly politicized — everything becomes a self-evident truism when you’re just starting to think about it. And it’s fair to call him out for preaching universal brotherly love and understanding with the utter exception of poor Paul McCartney, not to mention his ugly history of parental neglect, addiction, and domestic abuse. John’s cynicism, selfishness, and bitterness was as much a part of his identity as his sensitivity, his social conscience, and his wit. Just like everyone else, to some degree or another. People deserve forgiveness if they try to earnestly work through their various sins, as Lennon did, rather than deny or ignore or turn them into virtues. This is called humanity.

As usual with these kinds of exhaustive box sets, the bonus material is mostly unnecessary unless you’re a diehard. We get several retreads of the music via home demos, alternate album versions, studio jam sessions, and outtakes. Lennon’s too-short impromptu studio jams are a reassuring reminder that, despite his pressing metaphysical and political concerns, he still liked to unwind with a little Jerry Lee Lewis and Chuck Berry. The disc of “Essential” mixes strips away the record’s already sparse instrumentation. It only occasionally enhances the songs as we already know them. A minimal, almost dignified, solo piano version of “Remember” outdoes the album version, and the moving love songs “Look at Me” and “Love” are imbued with the extra tenderness supplied by a private recording.

Aided by a useful foray into primal scream therapy, Lennon comes in hot. “Mother” takes us right into the quivering heart of his lifelong familial trauma, laying his deepest pain out on a slab once and for all: “mother/ you had me/ but I never had you.” The tune’s starkness bursts through a multilayered arrangement. By the end, he’s screaming for his departed mother like a hungry baby begging for the parents who will never come to the rescue. Pair that with the absolute devastation of “My Mummy’s Dead” as an album closer and I’d argue that very few, if any, musicians of his caliber have ever dared to reveal themselves in their primal anguish so nakedly.

“Working Class Hero” still resonates, with its gunslinger guitar and plainspoken taxonomy of modern alienation: “As soon as you’re born, they make you feel small/ while giving you no time instead of it all/ till the pain is so big you feel nothing at all// They hurt you at home and they hit you at school/ They hate you if you’re clever but they despise a fool/ Till you’re so fucking crazy you can’t follow their rules.” Many radical sociological essays pretty much boil down to that: the failure of institutions like the family, education, media, and the free market to foster creative and healthy people. In the face of all that, maybe a working class hero is all you really can be, with the stoicism and grit that somehow sees you through.

Admittedly, it’s a bit rich to advise people on how to be a working class hero when you possess mind-boggling amounts of wealth and status. We should be a little bit skeptical, especially at the almost unforgivably cruel line “but you’re still fucking peasants as far as I can see.” Come again, captain radical? Still, it could also be argued that Lennon has a right to speak about being working class. If he hadn’t found himself in the exact right place and time with the right mix of people who encouraged his particular artistic gifts to flourish, this mouthy kid from a broken home in ’50s Liverpool would probably have ended up as just another yobbo at the corner chip shop, pissing away his life in pints and street fights.

The Plastic Ono Band. Photo: Wiki Common.

The contradictions between Lennon’s privilege and his radicalism foreshadow the way right wingers bellyache about “liberal elitists” in the media, while commanding plenty of prominent media space themselves. Listening to the music over and over again, in several different iterations, I never felt tempted to tell him to “shut up and sing.” But it’s obvious now how little telling the world to “hold on” really amounts to. Still, it is never useless to hear the fact of the matter: our collective fate really is in our own hands: “when you want/ really want/ you can get things done like they’ve never been done/ so hold on.” Given the current state of the world, holding on is just about good enough.

Is God really “a concept by which we measure our pain”? Personally, I tend to think of religion as an act of the imagination, very much like art itself. Every prayer is in some sense a self-portrait. So it’s natural to imbue our so-called pop idols with an aura of divinity, especially when their art speaks directly to what lies deepest within our souls. Nothing wrong with that — as long as you don’t forget that they’re people, too, though equipped with seemingly supernatural gifts.

When Lennon growls about “the freaks on the phone won’t leave me alone/ don’t give me that brother brother brother brother” in the sizzling “I Found Out” he knows perfectly well that people have turned him into their own personal Jesus (if not even bigger!). He is fed up with that: Lennon’s been taken for the messiah by too many fans for too long. He makes a frank rebuttal: “there ain’t no Jesus gonna come from the sky/ Now that I’ve found out, I know I can cry.” So there.

Especially in America, we tend to love our heroes to death. Maybe it’s because we can’t stand for our idols to have clay feet. Or that the democratic promise — we can be anything we want to be if we try hard enough — goes unfulfilled for more and more every passing year. But that’s no matter — if Elvis or The Beatles or whoever can do it, then maybe you can, too. Just try a little harder to be who you want to be, stretch out your arms a little farther. The sad truth is that, most of the time, we don’t.

Yoko Ono and John Lennon in Holland in 1969. Photo: Wiki Common

Listening to Plastic Ono Band moves me now because the music reflects what happens when someone who has accomplished everything he ever dreamed of (and more) realizes that it is not enough. And concludes that there’s more to life than getting what you want. In Lennon’s case, he’s totally fine with letting go of it all.

“God” grows in power as Lennon lists, over steadily plangent piano chords, all the various false idols he’s given up on, even if others haven’t, from Gita to Elvis to Kennedy to Jesus to Buddha to Yoga, until he settles on the biggest idol of them all — the Fab Four themselves. After that name drop he stops his world/historical denunciation hanging for a long moment in midair. For John Lennon, who had always arrogantly assumed that The Beatles were his band and who fomented their breakup as much as everyone, to say this and really mean it has got to be one of the most profound statements in all of popular music history. There are plenty of picayune motivations for him to slag off The Beatles, of course. But he ties his rejection into something much bigger: shedding grand illusions in a quest for vulnerability and honesty. The attempt is commendable.

Then the pleasant, almost casual music starts up again and he’s right back down to earth: “I just believe in me/ in Yoko and me/ and that’s reality.” Just like that. So, after having diagnosed the ails of modernity, screamed out his most deeply held traumas, and shrugged off his role in the biggest band ever, he’s content to have a riverside cuddle under a tree in the sun with the woman he loves. Amen, John. Here’s a nice warm cup of instant karma for you. Please remember to wave goodbye to the walrus.

Matt Hanson is a contributing editor at the Arts Fuse whose work has also appeared in American Interest, Baffler, Guardian, Millions, New Yorker, Smart Set, and elsewhere. A longtime resident of Boston, he now lives in New Orleans.

whew. much to swallow and digest. reminds me of discussions we used to have some decades ago, though someone would have mentioned the stones by this point.

and yet i can’t but wonder why the fuck the beatles? the are long gone. but are they the last hunk of rock you care about in depth? why?

can you say?

as for yoko i’m pleased to consider her as the stellar visual artist she was and remains.

but maybe i’m excluded from this discussion altogether by the fact that lately i’ve been digging into abba. can you believe it? and catching up on blond.

maybe i’m just stuck in the 80s or thereabouts. if you looked at my facebook feeds you might think i think Larry bird is still playing.

maybe there are times in most sports that won’t go away and can almost subsume the present, and maybe that’s a partial explanation for mike tyson’s need to bring retired greats and legends together, even though results are pretty sad.

and then there’s electronic media: as art spiegleman once observed, which makes everything simultaneous, doesn’t it.