Theater Commentary: Healers, Cool Your Heels

By Bill Marx

Throughout history, theater has been a place where the community has looked honestly at what is killing it.

Ontario’s Soulpepper Theatre Company is producing Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author on its 100th anniversary. A perfect meditation on the ambiguity of identity for our era of avatars and Facebook/Twitter/Instagram personae.

The post-COVID all-clear is being sounded, with robust fanfare, in the arts. Among Boston’s major theater companies, Arts Emerson and the American Repertory Theater are already using the word healing in the marketing for their upcoming productions: the A.R.T. is going all out via a late August production that will be staged amid the medicinal greenery of Harvard University’s Arnold Arboretum. The assumption, promulgated by stage companies, foundations, and rah-rah cultural support organizations, such as ArtsBoston, is that audiences are raring to come back. The return of live theater will be restorative, runs the argument, providing community and a sense of psychological reassurance to the well-heeled theater contingency.

So, let the healing begin and the good times roll in the aisles. Yes, 604,000 Americans died in the pandemic, with 4.08 million dead around the world. Vaccine shortages abound around the world in countries sunk in dire misery. I wondered in a 2020 column why American literature (including theater) almost completely ignored the 1918 pandemic. The fact is, the arts and culture crowd (creators as well as spectators) put mass death in the rearview mirror in order to surf the wave of the roaring economy of the ’20s. (Calvin Coolidge let the cat out of the bag in 1925: “The business of America is business.”) Is it any surprise that the old normal is returning pronto, now that it looks as if big business will be taking off? American theater has always been most comfortable whooping it up for a better future. Mourning the dearly departed — not so much.

But the arrival of a cure for what ails us, good for the bottom line as it is, may be exaggerated. As I write, the Delta variant is on the rise in all 50 states. Mask mandates are returning to some areas. Despite the vaccine, people are increasingly wary of mass gatherings in enclosed spaces. And, by the way, democracy is under dangerous threat. Who knows what lies ahead in the months to come? Perhaps the healers should take a look around and … cool their heels. For one thing, there has been an elemental change in the world’s reality that the survivors of the 1918 pandemic didn’t have to worry about. Nature — aside from the pampered fronds at the Arnold Arboretum — is showing considerable signs of climate crisis wear and tear: record flooding in Germany, drought and record heat in the American West, the Great Salt Lake is in danger of becoming a toxic dustbin, and, for the first time, the complete surrender of the Amazon rainforest, which is now emitting more CO2 than it absorbs. At this point, urgency is called for. Of course, that is not what arts marketing campaigns are about.

Rather than selling palliatives to a crowd anxious for quick reassurances, perhaps our theater companies should examine the circumstances we find ourselves in and explore how we got to where we are. That might inspire our stage artists to imagine where we can go from here. Why sell assuagement when, in the past, theater has diagnosed society’s diseases, including the afflictions of existence itself? Shouldn’t we face the damage we have done before we reach for the feel-good medicine, as soothing as that might be? The climate crisis is the subject of the passage below, from an essay in Terry Tempest Williams’s 2020 collection Erosion, but her point is applicable to the pandemic as well.

Not until we begin to understand the true costs of what we have lost and the pain we have inflicted on people and nature through the destruction of fragile landscapes and communities in the commodification and extraction of the Earth, can a healing between us take place. Our collective crisis of conscience and consciousness in this era of climate change is based on self-delusion, privilege, and our sense of entitlement, all of which continues to fuel the power and rapaciousness of our appetites. It is killing us.

Throughout history, theater has been a place where the community has looked honestly at what is killing it, from the Greeks and Shakespeare to Beckett, Brecht, Bond, and Kane. Their spectacles don’t offer reassuring rebuttals of what Freud called Thanatos, the death instinct. But primal questions were engaged and the chips fell where they had to — toward tragedy or tragicomedy. The question raised by today’s rush to oblivion is clear: Why are we murdering nature and, by extension, ourselves? Could there be a fitter, a more compelling topic for our stages? What’s more, the agents of destruction are intimately interconnected, climate change and racial hatred intertwined with big tech, income inequality, and the allure of fascism.

This challenge does not do away with Sir Toby Belch’s understandable ask that there be “cakes and ale.” They will always be welcome — but for the theater to matter, it has to serve up more than the celebratory. And that means taking risks, not settling for spicing up musical cakes and cocktails with feel-good liberal bromides about “empowerment” and “inspiration.”

There are no signs that Boston theatergoers will be confronted with shows detailing what is killing us. The seasons at our major regional theaters are overcrowded with previously hosannaed New York product or fodder aimed at Broadway. Regarding the demolition of the climate, the approach will be lite. The A.R.T. is mounting the world premiere musicals WILD in concert (“a new musical fable about a single mother struggling to hold on to her family farm and connect with her teenage daughter, whose determination to save the planet endows her and her friends with powers they never knew they had”) and Ocean Filibuster (“an epic Human-Ocean showdown”). Over at the Huntington Theater Company comes Hurricane Diane, “an enjoyably bonkers comedy” about global warming. Perfect — just as the Western US is going up in smoke! Our mid-to-small theater scene, hit hard by the pandemic, is gasping for air. There are, at least as of this writing, few announced efforts among the small fry to tackle climate change.

Few in the theater community are pointing out the theater’s lack of response to current realities. Our supremely supine theater critics — led by the don’t-rock-the-boaters at the Boston Globe and NPR — are primed to blurb-o-matic all they see for the sake of supporting local stages, which also means placating the foundations that give them funding. Media and economics dictate that the status quo will return, dressed up as the “new and concerned.”

So, what is a serious theater critic to do?

Never stop insisting that theater take up issues of ultimate concern. Powerful theater can be made out of why and how we are doing ourselves in. There are efforts around the country (among smaller theater companies) to produce shows that address the trauma of climate change. It most likely won’t happen here. But critics and others who care about theater must raise their voices and insist that it does.

In truth, the long-term artistic health of live theater may well be at stake. The drift into cultural marginality, nurtured by the death-in-life of Broadway, continues apace. Formidable competition that has a foot in the real world is growing online: hard-hitting documentaries and feature films from around the world, popular music howling about the poisoning of the planet. Our theater’s choice to “sit this one out” is symptomatic of its own death wish. American theater has not always confronted a national/global crisis with apathy. During WWII, numerous productions focusing on the conflict played on Broadway. (See Arts Fuse review of Broadway Goes to War). Sharp-tongued critic George Jean Nathan was right — most of these productions were mediocre at best. But theater artists accepted their responsibility to deal with the war, providing propaganda as well as skepticism. This is an honorable, indispensable goal, and there is no reason that some great theater couldn’t come out of it.

But that calls for radical change in the current system.

What I can do now is to write about theater that accepts today’s challenges. I will report on contemporary scripts that deal with current issues, from climate change and the rise of plutocracy to the appetite for authoritarianism. And from time to time I will pick a neglected play from the past that has something to say about what is happening now. Some texts stand out immediately. Jesse Green of the NYTimes recently pointed to the plays of Wallace Shawn staged via podcasts of The Designated Mourner and Grasses of a Thousand Colors. I would add his Evening at the Talk House to that list. (None of these scripts, according to my Google research, has been staged in Boston. Hey, Boston producers! A good notice in the NYTimes! In the New Yorker!) Shawn excoriates the blindness of the privileged classes, the entitled who are sunk deep in the “sleep of reason,” accepting, in the words of critic Lucas Spiro, “the immense, horrific violence necessary to maintain our consumer comforts.” Or those who welcome — or are empowered by — the approach of fascism.

Another obvious choice would be Pirandello’s modernist classic Six Characters in Search of an Author, which is celebrating its 100th birthday this year. What could be a better fit for our era of avatars and Facebook/Twitter/Instagram personae than a play about “characters” completely lost in their threadbare roles? This script’s nuanced use of irony and paradox examines the tension between art and life, between knowledge and actuality. This brilliant play spotlights communicative paralysis: it has become impossible for people to offer direct revelations of themselves, to provide an unmediated history of what occurred. They are trapped in reductive and/or distorting dramatizations in which they parrot someone else’s idea (spin, branding, marketing, propaganda) of what happened, of what the “facts” are.

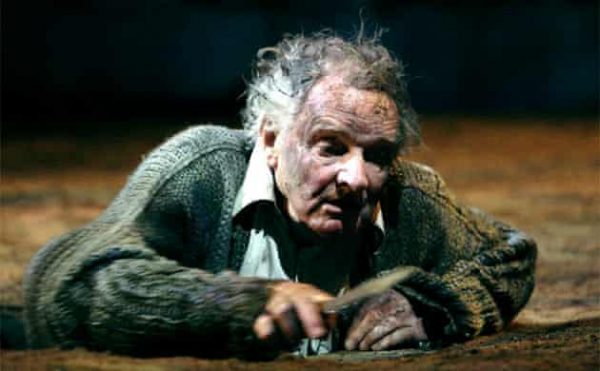

A scene from Sheffield’s Crucible Theatre’s 2005 revival of Edward Bond’s Lear, starring Patrick Godfrey (above). Photo: Catherine Ashmore

But Pirandello’s masterpiece is getting some (alas, only scant) notice. Ontario’s Soulpepper Theatre Company is offering an effective podcast production of the drama, which is free through this month. The play I wish to focus on next is one of the 20th century’s most powerful adaptations of Shakespeare, Edward Bond’s Lear, which is celebrating the 50th anniversary of its premiere at the Royal Court Theatre. The occasion is being passed over in silence. To my knowledge, there has never been a production in Boston of this wholesale, sweeping rewrite of the tragedy.

Bond is still writing at the age of 87, and he is one of the greatest English playwrights alive, and not just because of the historical importance of his 1965 play Saved, which helped topple censorship in England. (The others would include Caryl Churchill, Howard Brenton, and Howard Barker.)

Bond’s Lear reduces Shakespeare’s 5 acts to 3, and focuses on the construction and then the attempted demolition of a massive Wall that Lear is erecting to keep out the (largely imagined) enemies of his kingdom. His daughters, Bodice and Fontanelle (Goneril and Regan) secretly conspire to marry the Duke of Cornwall and Duke of North — the very foes that Lear fears. The monarch launches into a conflict with his daughters, is defeated, and becomes a refugee. Cordelia appears as an anonymous woman whose husband gives the outcast king a temporary haven.

When the play premiered in 1971, the Wall was obviously the Berlin Wall. Today, the image takes on a different, but still revelatory, significance. 50 years ago the script’s violence generated a backlash among critics and audience members. Some people walked out during the torture scene, which was modeled on Nazi experiments in the concentration camps. Contemporary dramatists don’t often explore violence, which makes Bond’s lifelong concern — propelled by his belief in the corrosive social/spiritual impact of the Holocaust and Hiroshima — so valuable. From his preface to Lear:

I write about violence as naturally as Jane Austen wrote about manners. Violence shapes and obsesses our society, and if we do not stop being violent we have no future. People who do not want writers to write about violence want to stop them writing about us and our time. It would be immoral not to write about violence.

Violence is one of the things that is killing us. In response, the imagination is called on to be a tool of defiance. For Theodor Adorno, art should go about resisting “the course of a world that unceasingly holds a gun up to mankind’s chest.” And now massive clouds of smoke from that world, generated by Western infernos (at least 88 major wildfires across 13 states), are wafting into our faces.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of the Arts Fuse. For just about four decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

A Happy Update!

After a decade long battle, Harvard University finally divested from fossil fuel this afternoon. A Harvard University student activist’s reaction: “It’s a massive victory for our community, the climate movement, and the world — and a strike against the power of the fossil fuel industry.” So the American Repertory Theater, the recipient of millions of dollars from Harvard University, is no longer greenwashing … on to Broadway!

Just in from Bill McKibben’s excellent column on substack: